Image: Claire Diana Hallpike-Selby

This post is sponsored by Helion

Survival during World War II wasn’t just about tactics and firepower—it was about adaptability, human connection, and the will to persist. For Allied prisoners of war in Italy, the odds were grim: only 6–7% survived captivity. Yet, within those stark statistics lie extraordinary stories of defiance and endurance.

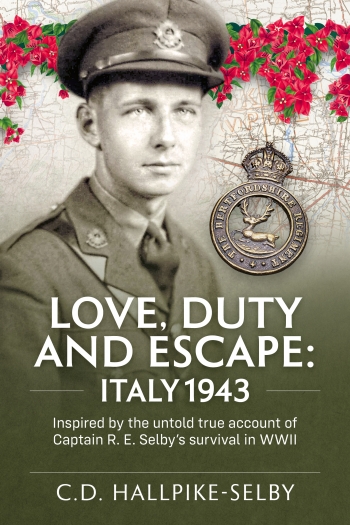

One of those stories belongs to Captain Reginald Edward Selby, a young officer from Hertfordshire, England. His perilous escape from captivity and eventual crossing into neutral Switzerland is more than a tale of adventure—it’s a case study in trust, preparation, and the psychology of survival.

From Capture To Escape

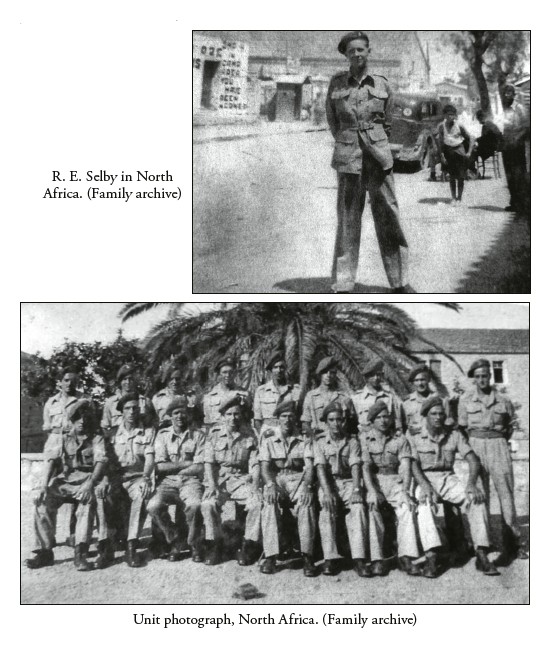

At just 19, Selby joined the H.M. Forces. In July 1941, aged 20, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. In December 1942, his ship left for North Africa. Like many young officers, he had never traveled abroad, yet quickly found himself responsible for men in a brutal theater of war. When his unit was overrun, he was captured and sent to Italy as a POW. Even transport carried mortal risk—the ship he was on narrowly avoided RAF fire before arriving at Camp PG 49 in Fontanellato.

September 1943 changed everything. With Italy in turmoil, Selby and a fellow prisoner seized the opportunity to escape. They navigated not only physical threats but also the moral complexities of war. Italian families risked everything to hide Allied soldiers, often under the threat of fatal reprisals. German raids were ruthless—one soldier was discovered and executed in the very house where Selby hid. That near miss underscored both the fragility of survival and the immense courage of the civilians who supported him.

With the help of partisans, Selby acquired false papers and a pathway north—one that would demand every ounce of his endurance and every lesson of his training.

The Value Of Local Knowledge

An escape across enemy territory required more than courage. It required expertise. In Selby’s case, the expertise came from men like Umbertino, local guides who combined intimate knowledge of terrain with tactical wisdom.

“After dark, Umbertino returns. ‘Did you get some sleep?’ he asks.

‘A little,’ comes Reg’s unconvincing reply. It is impossible to relax with the

border so near and the risks so high. ‘Stay close but walk naturally next to me, as if we are friends, co-workers finishing a shift and so out after the curfew. Say nothing till we are past the last house,’ warns the guide.

They set off together silently. After a while, the path ends and they climb a low fence to start crossing open country. There are empty fields, thickets to push through and streams to cross. The dark outlines of cattle dot the landscape and they weave past farmhouses, outhouses, barns and huts, closer and closer to the Swiss border.

By the middle of the night, they reach a high wire fence that blocks the path. The guide explains that it is guarded by patrols who walk a mile in each direction and back again. This is the border. This is the last and perhaps most dangerous part. Anyone seen out at night here will be shot on sight. Umbertino points across the land in front of them and explains the next steps. ‘There is a brief window of time when you can get past the guards, through the fence and out of range on the other side before the guard returns.’”

The right guide didn’t just increase Selby’s odds—he transformed an impossible task into a navigable one.

“‘How do I get past the fence?’

‘There are water culverts under the fence at intervals of a quarter of a mile. This one, straight ahead, is the one you must go through. You climb into the culvert and up through the pipe. You then run straight on to the river, swim across it and climb up the bank on the other side. Then you are in Switzerland.’”

Ingenuity and local intelligence turned natural obstacles into pathways to freedom.

The Psychology Of Escape

Physical endurance alone was never enough. The mental battle was relentless—fear, fatigue, and doubt pressed as heavily as enemy patrols. Selby’s story highlights the importance of mental frameworks, training, and self-talk in surviving high-stakes challenges.

“The spring flow is strong and he cannot cross straight but has to work with the water to cut a diagonal line across. In the darkness, he must keep the goal clear in his sights – the black outline of the bushes on the far bank. He hauls each arm out of the swirling, dragging water, weighed down with the simple jacket, and again and again plunges each one back in to pull himself nearer to the vague silhouette ahead. He heaves at his muscles that are weak with cold, his teeth starting to chatter involuntarily. ‘Not now! You can’t fail now!’ he says to himself. As if on cue, an image from his training days enters his mind. He suddenly remembers – and he smiles even in that desperate moment of extremis – the shouting face of the sergeant major and his seeming relish at making the young recruits march into the icy Welsh sea. That apparently pointless activity now makes perfect sense. This river crossing in the dark and cold is exactly the kind of test that his training was preparing him to face. Still smiling, and despite the icy water rushing all round him, he feels a warm surge of gratitude run through his body. Another image flickers into his mind: of his photo in his officer’s uniform and regimental cap, decorated with its symbolic badge of a deer, a hart, fording a river. ‘This is my ford and I am a Hertfordshire lad!’ he tells himself, gritting his teeth and willing his arms and legs forward through the icy flow. The thought of Hertfordshire, of home, of support and a place where he belongs strengthens his determination. He pushes ahead with new energy for the last few strokes until, at last, he can grasp hold of the tough, wild grasses on the opposite bank. He hauls himself up out of the water, dripping wet and with the soles of the cheap shoes flapping. There is no time to catch his breath – and he will surely succumb to the cold if he stops now. Reg casts a glance around then heads up the slope away from the river as fast as he can.”

What emerges is clear: resilience isn’t just a matter of strength—it’s a matter of identity. Selby’s ability to anchor himself in home, heritage, and training gave him the resolve to move forward when his body faltered.

The Border As The Final Test

The closer to freedom, the higher the stakes. The Swiss border was heavily patrolled, and every step carried the possibility of discovery.

“By the middle of the night, they reach a high wire fence that blocks the path. The guide explains that it is guarded by patrols who walk a mile in each direction and back again. This is the border. This is the last and perhaps most dangerous part. Anyone seen out at night here will be shot on sight. Umbertino points across the land in front of them and explains the next steps. ‘There is a brief window of time when you can get past the guards, through the fence and out of range on the other side before the guard returns.’”

Even in that final stretch, survival demanded both composure and speed.

“As a country boy, he knows that you catch the rabbit when it moves, not when it is still, but move he must. The huntsman here is his enemy, like the sniper in the dark that took Private Wells’s life just inches from him on that dark North African night.”

And even when the escape was technically complete, the mind still wrestled with uncertainty:

“Suddenly in the dark, he hears the click of a gun being cocked a few metres ahead. He stops still in shock and fear, not daring to look up in its direction. Then he hears the challenge barked out in German, ‘Hände hoch!’ (Put your hands up!) He stands immobile in the pose of running, dumbfounded and shivering with cold and disbelief. No! No! Fear takes hold – a gun is pointed directly at him. Is this how it ends? But then fear is quickly replaced by a strange feeling of guilt. After all the seven and a half months of effort by so many to hide him and keep him safe, has he really fallen back into the hands of the Germans somehow? This should be the Italian part of Switzerland, so why is a German here?”

The answer revealed itself in a flicker of flame.

“The guard stands pointing his gun at the dripping and bedraggled figure, but it is not aimed and ready to fire. Instead, he is resting it nonchalantly on one hip, so that he can casually light a cigarette with his free hand. At the sound of the striking match, Reg looks up at the figure in the feeble glow of the flame – and sees that the guard’s uniform is Swiss! Relief like a hot wave floods through his whole being. He collapses onto his knees in the scrub. The guard is Swiss-German. He is safe.”

Neutrality in Switzerland was more than geopolitical—it was the difference between life and death. For Selby, it was the end of one of the most harrowing journeys of his life.

Why This Story Matters Today

Claire Diana Hallpike-Selby captures this true account in Love, Duty and Escape: Italy 1943. The book goes beyond recounting a soldier’s escape. It captures the humanity, fear, and determination that defined the experience.

For military historians, it’s an intimate portrait of a POW’s struggle. For adventure enthusiasts, it’s a story of danger, trust, and triumph. But beyond that, it underscores timeless truths: the importance of relying on others, the resilience forged through training, and the role of identity in sustaining determination.

Selby’s story is not just about surviving war—it’s about the enduring human capacity to find strength in the darkest of moments.

Love, Duty and Escape: Italy 1943 – Who was Captain R. E. Selby? [VIDEO]

LOVE, DUTY AND ESCAPE: ITALY 1943 | CLAIRE DIANA HALLPIKE-SELBY