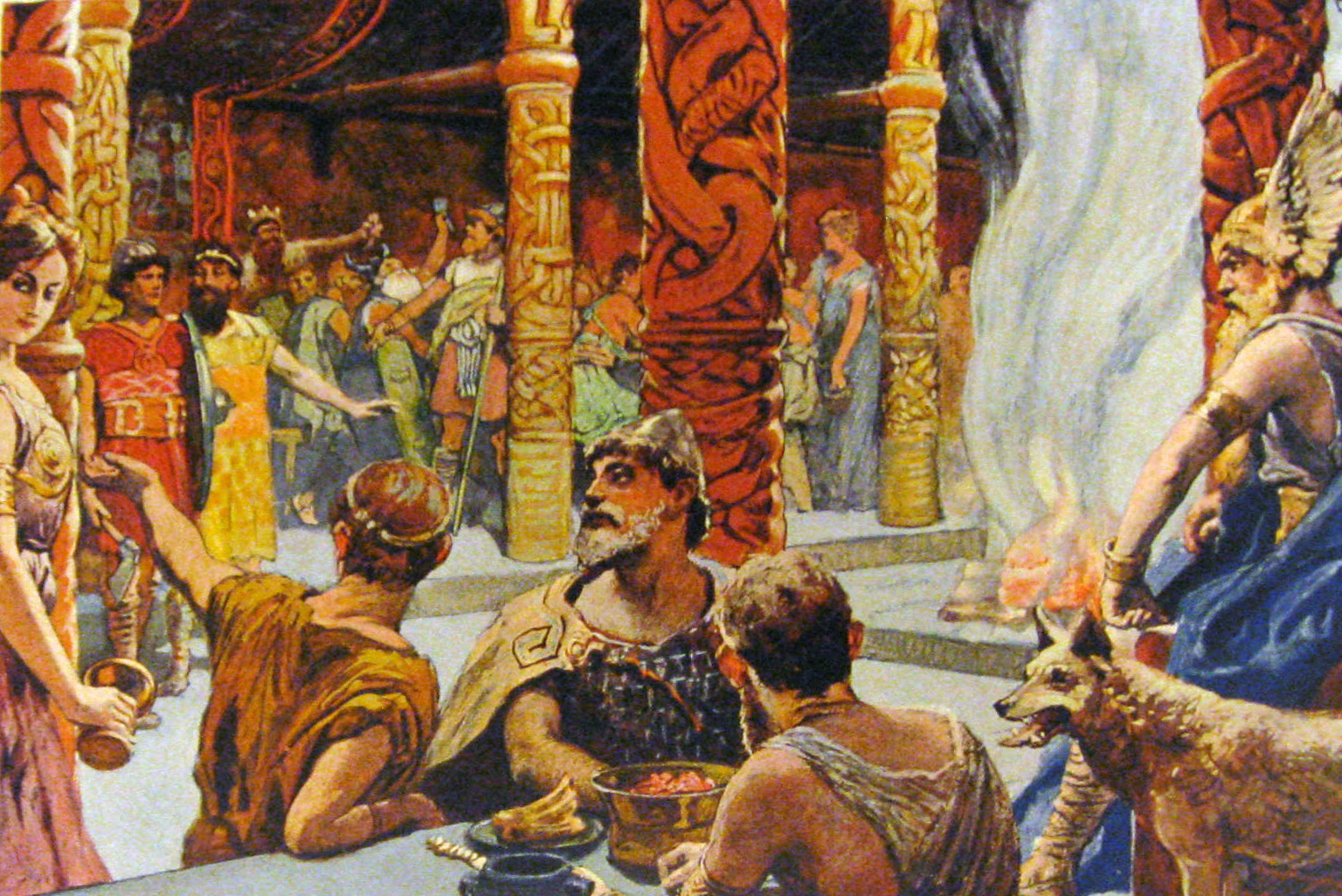

Feast at Valhalla. Illustration by Emil Doepler, 1905

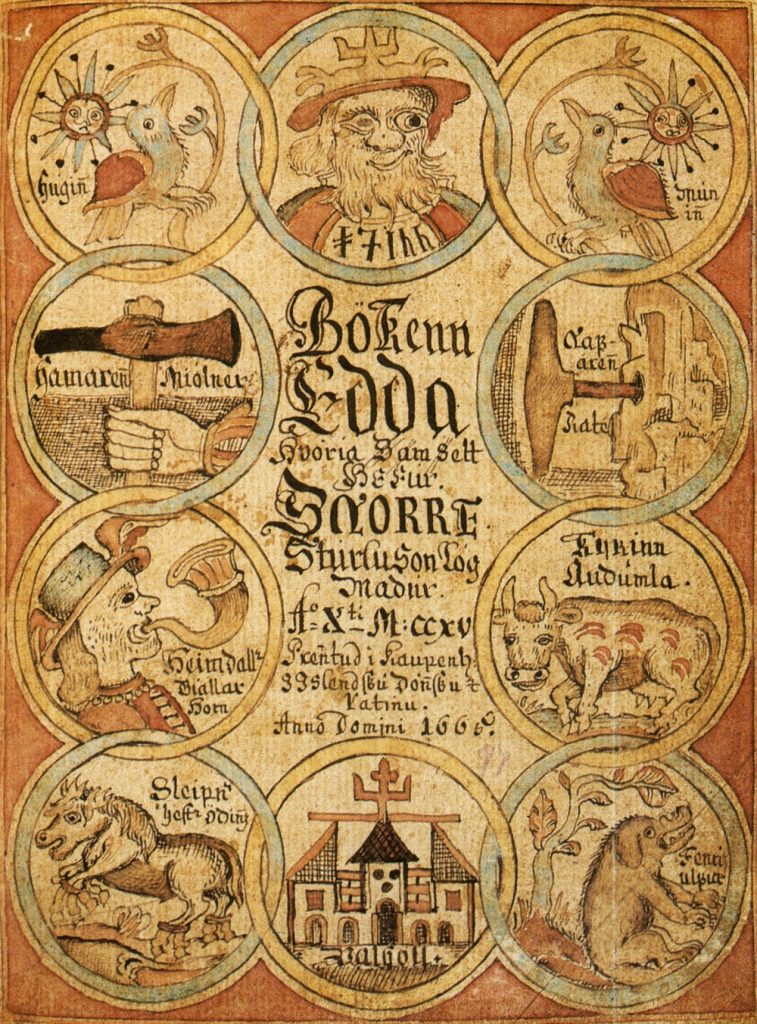

In 1842 George Webbe Dasent completed his translation of Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson’s early thirteenth-century The Prose Edda – often referred to as the Younger (Snorra) Edda – which is considered a vital text informing Norse mythology and Viking culture.

In a review of Dasent’s translation, the writers at The Times of London seemed astounded at the Edda’s praise for drinking – which contrasted conservative Victorian sensibilities:

But the Norseman looked merely for copious libations of mead and swine’s flesh, without stint, and certainly shows some powers of imagination in conjecturing celestrial contrivances for securing an inexhaustible supply of these dainties. The praises of mead are everywhere sung, for the poor Norseman seems to have coveted nothing higher… Drinking mead, eating swine’s flesh, and fighting in mortal combat, constitute the joys of Valhall[a], the Norseman’s Heaven.[1]

As the Times indicated, there are endless references to imbibing in the Younger Edda. Odin, the most powerful god in the Norse pantheon, “needs no meat, wine is to him both meat and drink…” In Valhalla, the majestic destination for Viking warriors killed in battle, there were those “whose duty it is to serve… bear drink and tend the… alehorns…”

The most famous example of drinking prowess appearing in Norse mythology, however, occurred at King Loki’s castle called Jötunheim. According to the Edda, Thor and his companions came upon the massive castle one day with “a great hall” and entered it. Once inside, Loki “looked slowly on them, and smiled scornfully” before telling the travelers it was “‘late to ask tidings of a long way’” but that if they could perform some skillful feats, they would be allowed to stay the night:

Loki asks Þórr [Thor], what those feats may be which he would be willing to show before them, answering to the tales men had made of his great works. Then said Þórr that he will rather begin a drinking-bout with any man. Utgarð’s Loki says that may well be, and goeth into the hall and calls his cupbearer, bids him take the horn of harm that his thanes are wont to drink of. Then strait way comes forth the cupbearer with the horn and gives it into Þórr’s hand.[2]

“Not off in three” gulps

Loki explained to Thor the horn would be “well-drunken” if downed in one gulp but that “some men drink it off in two,” and lesser men finish it “not off in three.”

A thirsty Thor examined the horn and concluded it was not large, but rather long, and proceeded to swill it thinking one gulp would be sufficient. After tiring, he set the horn down, but it was “hard to tell whether it were now any lower in the horn than before.” Loki said to Thor: “‘Tis well drunken and (yet) not much, I would not have believed, had it been told me, that AsaÞórr could not have drunk a greater draught; but I wish thou must wish to drain it off at the second drink.’” Defiantly, Thor put the horn back in his mouth thinking…

…he shall drink a greater draught, and drinks deep as he was wont; and yet sees that the tip of the horn will not go up so much as he likes, and when he took the horn from his mouth, it seems to him now as if he had drank less than the first time, but the horn could now be borne without spilling. Then said Utgarð’s Loki: “How now þorr! thou must not spare thyself more in a drink than befits thy skill; so it seems to me, if thou shalt now drink off the horn the third drink, thou must strive to make this most of all: but never wilt thou be called among us here so great a man as the Asa say, if thou makest not more of thyself in other games than it seems to me will be (the case) in this.” Then was Þórr wrath, sets the horn to his mouth, and drinks amain the best he can, and held to the drink as long as might be; but when he saw into the horn, now at last some small change had come upon it; and then he gives up the horn, and will drink no more. Then said Utgarð’s Loki. “Easy to see is it now, that thy might is not so mickle as we thought; but wilt thou try more games?”[3]

“Thou hast drunk in the sea”

Thor played three games that day and seemingly failed in every attempt to impress his host. Nevertheless, Loki allowed Thor and his men to stay in Jötunheim. The next day they ate and drank together, and before Thor and his companions set out to leave, Loki mentioned to Thor that he hoped he would not see him again. “‘Now shall I tell you the truth, since thou art come out of the burg, that if I live and may have my way, then shalt thou never more come into it: and by my troth I wish thou hadst never come in, if I had known before thou hadst so much strength in thee, and that thou wouldst have brought us so near to great mishap.’”

Loki then explained that Thor had actually surpassed his expectations in all the feats he performed, and that when he “‘drankest of the horn, and it seemed to thee to sink slowly… the other end of the horn was out in the sea, that sawest thou not, but now when thou comest to the seashore, then wilt thou be able to see what a sinking thou hast drunk in the sea, that is now called the ebb.’” When Thor heard of how Loki’s magic made him lower the sea level and the trickery played on him, he reached for his hammer to smash the castle, “but when he should dash it for will forthwith break down the burg, then sees he there vales wide and fair, but no burg.” Neither was Loki to be seen.[4]

[1] “Norse Mythology” The Times. London January 7, 1843. George Webbe Dasent, The Prose or Younger Edda (Stockholm: Norstedt and Sons, 1842). See: Andrew Wawn, The Vikings and the Victorians: Inventing the Old North in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2000).

[2] Dasent, The Prose or Younger Edda, 40-46, 59.

[3] Ibid. 60-61. AsaÞórr (Thor of the Æsir). Æsir are the principal gods in the Norse pantheon.

[4] Ibid. 63-65. See: Stefanie von Schnurbein, “The Function of Loki in Snorri Sturluson’s ‘Edda,’” History of Religions 40, no. 2 (2000): 109-24.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.