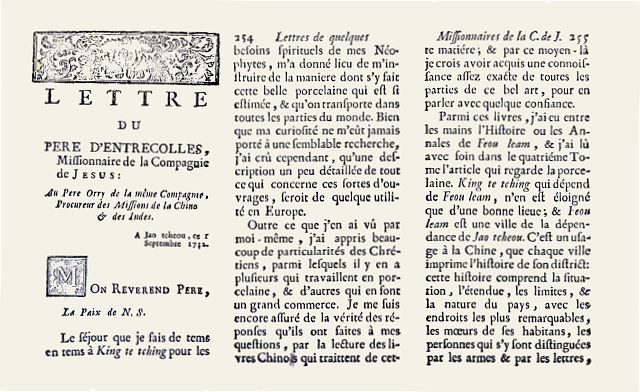

Teapot with relief and painted decoration of actresses, Vezzi porcelain factory, c. 1725. Photo by David Jackson, CC BY-SA 2.0 uk

Victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win.

Sun-Tzu, c. 5th century BC

They had a knack for designing the luxury life of European nobility. Although involved in controversies such as industrial espionage, the Vezzi porcelain factory offered a touch of the exotic to society, crazy about new things and those things that reminded them of distant and exciting countries.

Trade and Society of the 18th Century

In the 18th century, global trade saw a boom never seen before. European society was interested in new luxury goods that added a significant touch to their luxurious life. That life was marked by two interesting trends of the time: hot drinks and socializing hubs. Drinking hot chocolate in a coffee house in the center of the big city was more popular than in the royal court, so fashionable in the previous centuries. Exchanging the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment with a cup of hot chocolate was a hot trend. And drinking from a special cup was a matter of prestige.

Opportunities on the Market

Francesco Vezzi, born in 1651 in Udine, was well aware of the opportunities the beginning of the 18th century offered to an ambitious businessman. When he was young, he worked as a goldsmith and was interested in financial speculation. It is not known why he decided to enter the porcelain business, but he entered it in 1719, when he was in Vienna. There, he became familiar with the business Claude du Paquier started in 1718. From Vienna, Francesco sent financial support to his son Giovanni, born in 1687. Considering the cultural, social, and economic development of the era, investing in this business seemed a logical move. The target market, nobility hungry for knowledge, adventure, and a lifestyle that echoes the exotic, was growing. And the investment would develop in the city already famous for its appreciation and sense of luxury life and aesthetics.

Controversy: Industrial Espionage

The booming interest in exotic luxury items in this era boosted the interest in the secret of their creation. So, it’s no wonder that people like Father Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles, who visited Jingdezhen, China in 1712, revealed to Europe the manufacturing methods of Chinese porcelain. This is considered an early case of industrial espionage. Something similar happened with Francesco Vezzi. Apart from du Paquier, while he was in Vienna, he also met Christoph Conrad Hunger, a duplicitous man who previously worked for the Meissen porcelain factory. In 1719, he moved to Vienna, where he started to work for du Paquier. During this era, men like Hunger were highly sought because of their expertise and skills. Hunger could provide access to kaolin clay that was used for Meissen and expertise.

Exotic Motifs

The initial idea for the production was good. The factory, operating for seven years, produced porcelain tableware with many oriental-inspired motifs. On the hard-paste porcelain from this factory were tropical landscapes, exotic birds, flowers, and other exotic decorations. Vezzi often designed product models by himself, offering them in deep blue, green, brick red, and yellow to the target market, having a special taste for luxury life.

Why Couldn’t Vezzi Porcelain Survive?

The factory was closed in 1727. Although the demand for these products was growing, Vezzi and his son didn’t consider a few facts that led to their ultimate fall. The Vezzi factory was first a commercial factory supporting itself. Most of the businesses of the era supported themselves with the state or ruler’s aid. That made the situation worse when they entered into financial difficulties that would lead to their dissolution in the end. Also, the raw materials probably weren’t always ideal. And it was expensive to import them. The factory also lacked a skilled workforce. There was also competition from Meissen and the growing Doccia factory. The ultimate nail in the coffin was Hunger’s betrayal. In 1727, he came back to Meissen with the information about the Venetian factory. Shortly after, the export of Saxon clay was banned.

Did ambition destroy Vezzi Porcelain? Maybe. But his case is a story of an individual in the 18th-century business world, still developing and preparing the real opportunities for future brands.