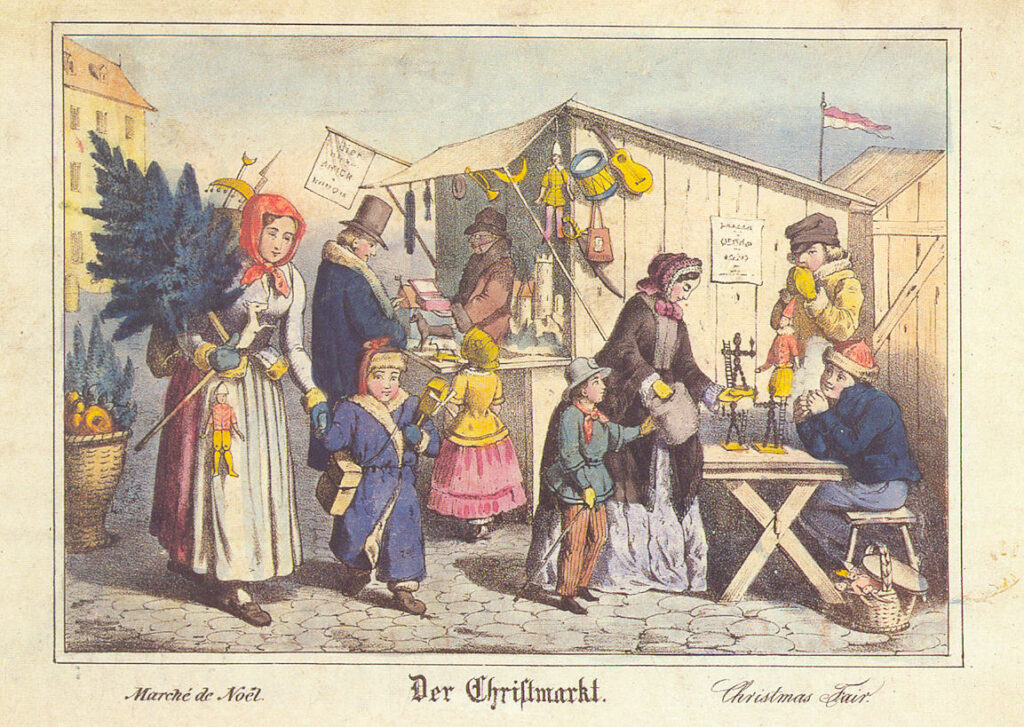

Christmas market in Berlin by J.S.L. Halle, 1796

The modern proliferation of Christmas markets in Europe, a spectacle of light, commerce, and tradition, represents one of the continent’s most successful and enduring cultural deployments. The placement and evolution of these markets have historically been dictated by strategic considerations. These are trade routes, political stability, and the burgeoning demand for festivity.

The lineage of this tradition moved from its disciplined, medieval origins as a localized trade ordinance to its current status as a linchpin of modern European tourism and soft power projection.

The Medieval Blueprint

The genesis of the European Christmas market is not rooted in simple holiday cheer but in a pragmatic necessity for late-year commerce. In the austere climate of the medieval era, localized markets provided essential logistical support for communities bracing for winter.

The first documented precursor to the modern market is often cited as the Striezelmarkt in Dresden, Germany, established in 1434 by Frederick II, Elector of Saxony. However, earlier, less formal “Winter Markets” or “December Markets” had already been granted charters by powerful sovereigns and bishops in other strategic urban centers. Vienna’s Christmas markets in Europe, for instance, trace their origins to a charter granted by Albert I in 1296, permitting a Krippenmarkt (Crib Market).

These early events were tightly regulated and served a critical function. They provided meat, hardy winter produce, and, significantly, crafts and durable goods necessary for survival or celebrating the upcoming religious feasts.

The establishment of these markets was a display of sovereign authority and a guarantee of commerce. They were a vital operational decree ensuring the continuity of the local economy before the onset of the deepest cold.

The early inventory was utilitarian: wood carvings, spices, and baked goods like Dresden’s famous Stollen. Unlike today’s expansive cultural mission, the focus was tactical and immediate.

The Renaissance and Baroque Shift

As Europe entered the Renaissance and the Baroque periods, the function of the markets began to shift. The increasing prosperity of the merchant class, coupled with a cultural move toward more elaborate domestic celebrations, transformed the strictly utilitarian winter market into a more festive, consumer-oriented spectacle.

This era saw the market’s mission expand from basic provisioning to cultural enrichment. Key urban hubs along the major trade arteries, from Nuremberg to Strasbourg, began to formalize the traditions. They specifically branded them around the Advent and Christmas seasons.

Nuremberg’s Christkindlesmarkt

By the 17th century, the Nuremberg market was strategically positioning itself as a hub for ornate seasonal toys and crafts. The market’s shift to selling gifts and decorations, rather than just necessities, broadened its operational profile.

Christkindelsmärik in Strasbourg, France

The Christkindelsmärik, first recorded in 1570, shows how the tradition was being strategically integrated into non-Germanic territories. It acted as a cultural exchange point between German and French spheres. This integration underscored the tradition’s adaptability and enduring appeal across political boundaries.

The markets began to feature dedicated food and beverage items—the spiced wine (Glühwein) becoming a signature feature, analogous to a stable, reliable piece of forward-deployed equipment. This specialization enhanced the visitor experience and began to attract patrons from greater distances.

The Modern Transition: From Local Commerce to Global Tourism

The true transition of the modern European Christmas markets in Europe in a major international event is a 20th and 21st-century phenomenon. Following the devastations of the World Wars, the markets were strategically revived as symbols of cultural continuity, peace, and cross-border cooperation.

In the late 20th century, the rise of affordable intra-European travel (enabled by developments like the Schengen Agreement and low-cost air travel) catapulted the markets into a position of major global significance. Today, they are a primary driver of Q4 tourism, a complex logistical operation involving massive infrastructure setup, security coordination, and international marketing.

Economic Impact

Cities view their Christmas market as a crucial economic asset, a deployment that boosts local retail, hospitality, and artisanal industries.

Soft Power and Diplomacy

The markets also serve as an annual, highly visible platform for cultural exchange. Attending a market in a foreign capital is often a routine yet powerful act of demonstrating respect for European traditions.

Consistency and Quality

The most successful modern markets maintain a high degree of fidelity to their historical inventory (handicrafts, traditional foods) while integrating modern amenities and sustainability efforts—a commitment to mission readiness and evolving standards.

The tradition of the Christmas markets in Europe thus works on multiple levels: it preserves a medieval trade ordinance, celebrates Renaissance cultural enrichment, and, in the modern era, contributes to a sophisticated tourism and diplomatic mission. It is a carefully managed cultural asset, strategically positioned every year across the continent to deliver joy, commerce, and a tangible connection to European history.

One thought on “The Transformation of Christmas Markets in Europe”