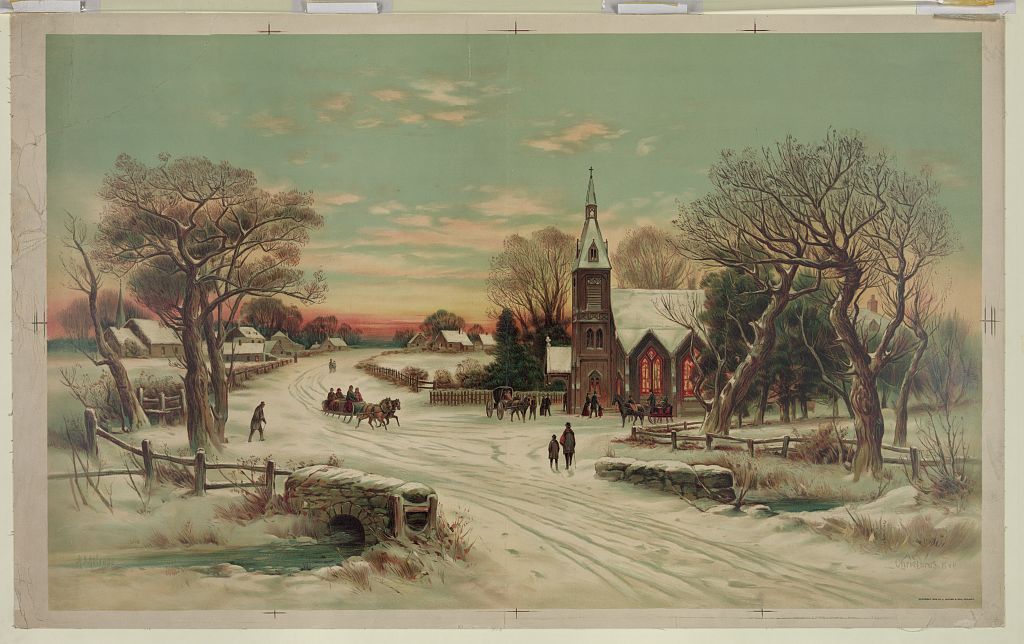

Christmas Eve, graphic by Andrew Melrose and Joseph Hoover, Philadelphia, United States, 1898

While history is often written in ink, it is just as often painted in light and shadow. For those who study the long arc of human culture, Christmas isn’t just a calendar milestone; it is a masterclass in branding and visual evolution. The winter aesthetics we recognize today—the deep evergreens, the sharp contrasts of candlelight against velvet shadows, the clinical purity of snow—didn’t happen by accident. They were curated over centuries, moving from pagan grit to Victorian polish.

The Origin Story: From Saturnalia to Starkness

Like any cultural icon, the “look” of the season has a gritty origin story. Before it was all precision-cut lead crystals and minimalist Scandi-decor, the winter aesthetics of the ancient world were about survival and defiance. The Roman Saturnalia was a riot of color and reversal, a chaotic burst of life against the encroaching gray of the solstice. It was a balance of the profane and the profound in its rawest form.

But as the Middle Ages took hold, the visual language shifted toward the symbolic. The evergreen wasn’t just a plant; it was a “voice for the voiceless” nature that refused to die. Later, when the first trees were brought indoors and wired with candles to mimic the stars, it was a bold pivot in winter aesthetics. It moved the celebration from the public square into the private, candle-lit sanctuary. It took a wild, external tradition and gave it a controlled, domestic framework.

The Victorian Pivot: Scaling the Global Brand

If you want to know how the season became a global juggernaut, you have to look at the 19th century. This was the era of the “Great Pivot.” In 1848, a single sketch of a Royal family gathered around a decorated tree at Windsor Castle changed everything.

Suddenly, winter aesthetics became aspirational.

In a calculated move of cultural distribution, the arbiters of 19th-century taste leveraged the emerging power of the mass-circulation printing press to export this specific visual identity across borders. They transformed the old-school folk traditions into a refined, bourgeois sentimentality. The statistics of the era reflect this boom: by the late 1800s, the production of glass ornaments in Germany skyrocketed to hundreds of thousands of pieces annually to meet international demand. The aesthetic was no longer just a vibe; it was an industry.

The Soft Power of the Hearth: Modern Winter Aesthetics

Today, the stakes for winter aesthetics are higher than ever. In the halls of international influence, the visual language of the season is a tool for connection. When a northern nation hosts a light festival, they aren’t just lighting candles; they are deploying a specific, minimalist brand of winter aesthetics that emphasizes sustainability and communal warmth.

Whether it’s the stark, brutalist winter scenes of mid-century cinema or the lush, maximalist displays of modern retail capitals, these visuals serve a purpose. They are “escapism at the highest level.” They remind us that even in the darkest months, there is a way to curate light.

As we look toward 2026 and beyond, the “Art of Christmas” will continue to evolve, opting for a deliberate, slow-burn transformation rather than a sudden overhaul, blending ancient shadows with high-tech digital projections. Because in the end, winter aesthetics are about more than just a holiday—they are the visual record of how we choose to endure the cold.