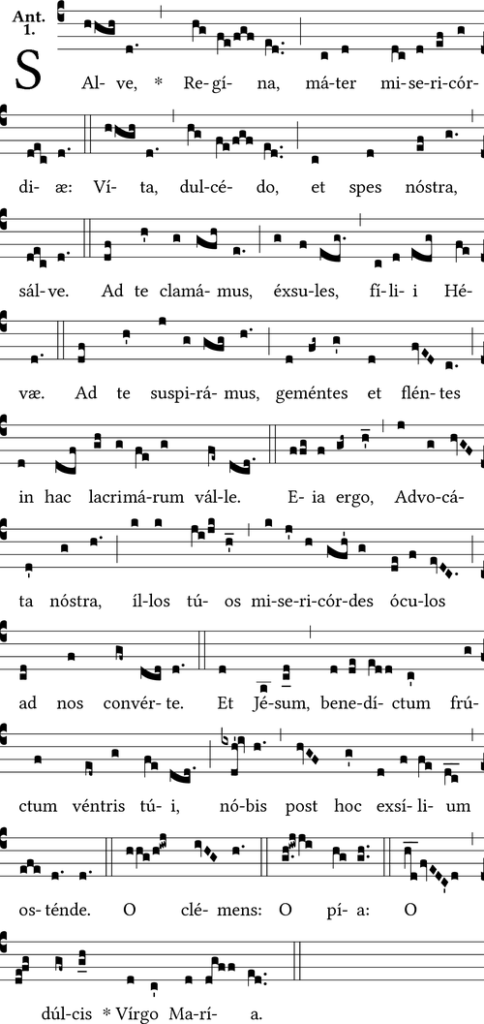

Graduale Aboense, hymn book of Turku (detail). Finland, 14th-15th century

For centuries, long before concert halls, recording studios or streaming platforms, a single human voice carried Europe’s most influential soundtrack. Sung in stone monasteries and echoing beneath vaulted cathedrals, Gregorian chant was never designed for performance or profit. It was created for something far more ambitious: shaping the spiritual, cultural, and political identity of a continent.

Today, Gregorian chant has a value as a legacy deeply rooted in European culture.

The Origins of Gregorian Chant: Order, Unity And Power

The story of Gregorian chant begins in the early Middle Ages, at a time when Europe was fragmented by language, local customs and political rivalries. The Church, one of the few institutions operating across borders, needed a unifying voice.

Traditionally associated with Pope Gregory I (reigned 590–604), Gregorian chant was less a single invention than a carefully curated system. Existing regional chants, from Roman, Gallican, and Frankish traditions, were standardized into one musical language. The goal was clarity, discipline and cohesion.

This was not an artistic experiment. It was a strategic one.

By establishing a uniform sacred music, the Church reinforced theological consistency and influence across emerging European states. In an era without print, Gregorian chant functioned as both doctrine and diplomacy, transmitted orally, memorized collectively, and shared across borders.

The Minimalist Sound

To modern ears, Gregorian chant feels strikingly minimalist. No harmony. No rhythm in the modern sense. No instruments. Just a single melodic line flowing freely with the Latin text.

That simplicity is intentional.

Chant was designed to remove ego from performance. There is no soloist, no applause, no virtuosity. The voice becomes a vehicle for the word, not the other way around. The result is a sound that feels suspended in time, neither fast nor slow, neither joyful nor mournful, but contemplative.

This restraint is precisely what makes Gregorian chant revolutionary. It established the foundations of Western musical notation, modal theory, and vocal discipline, systems that would later shape Renaissance polyphony, classical composition and even modern film scores.

Gregorian Chant As Europe’s Intangible Heritage

Long before UNESCO coined the term “intangible cultural heritage,” Gregorian chant embodied it. It is not an object that can be displayed behind glass. It exists only when practiced, transmitted and lived.

Monastic communities, from France to Spain, have preserved chant not as performance art, but as a daily ritual. This continuity, spanning more than a millennium, is almost unmatched in European cultural history.

For those engaged in cultural dialogue, Gregorian chant offers a compelling case study: a shared heritage that transcends national identity while remaining deeply European. It belongs to no single country, yet shaped them all.

The Modern Revival

In the late 20th century, Gregorian chant re-entered public consciousness in an unexpected way: the charts. Recordings by monastic choirs found global audiences seeking calm in an increasingly accelerated world.

But the revival was about need.

In a digital age defined by noise, Gregorian chant offers silence with structure. Neuroscientists have since explored its meditative effects, while architects and acoustic designers study how chant interacts with sacred space. It also helps travelers who seek immersion.

Anchored to Purpose

What makes Gregorian chant endure is not its age, but its adaptability. It has survived political upheaval, religious reform, Enlightenment skepticism, and modern secularism by remaining anchored to purpose.

It teaches discipline without rigidity, unity without uniformity, and tradition without stagnation.

In a world negotiating identity, heritage, and continuity, Gregorian chant reminds us that legacy is not about preservation alone. It is about transmission, carefully, patiently, across generations.

Gregorian chant represents a shared European language older than borders themselves.

It also remains what it has always been: a sound that connects past, present, and future—one breath at a time.