Carnival arrives in a blur of masks, music, and sugar-dusted indulgence, and at the heart of it all are fritters. From the winding calli of Venice to the stone-paved squares of Dalmatia, fritters have long signaled a season of celebration. Crisp on the outside, tender within, they are more than festive sweets. These edible heirlooms were passed from manuscript to memory, from monastery kitchens to modern bakeries.

As culinary historians turn their attention to Europe’s festive tables, fritters are emerging as one of Carnival’s most enduring traditions. Their story stretches back centuries, carried through cookbooks, travelers’ accounts, and the scent of hot oil drifting through winter air.

Fritters In Medieval And Renaissance Europe

The roots of fritters lie deep in medieval Europe, where frying dough in fat was both practical and celebratory. Before Lent’s austere weeks, households used up eggs, butter, and lard to prepare them. Fritters, or in other words simple mixtures of flour, eggs, milk, and sometimes fruit, became the perfect solution.

In Venice, they evolved into fritole, an iconic sweet of the Republic. Street vendors known as fritoleri sold them from wooden stalls, their recipes guarded and refined across generations. Raisins soaked in grappa, pine nuts, citrus peel, and saffron enriched the dough, reflecting Venice’s position at the crossroads of trade.

Bartolomeo Scappi, the great Renaissance chef, included fritter variations in his monumental 1570 cookbook, Opera. Later writers and gastronomes continued to document them, weaving fritters into the broader tapestry of European festive cuisine. By the 18th and 19th centuries, nearly every region had claimed its own version.

A 1606 Recipe: Fritters In Epulario

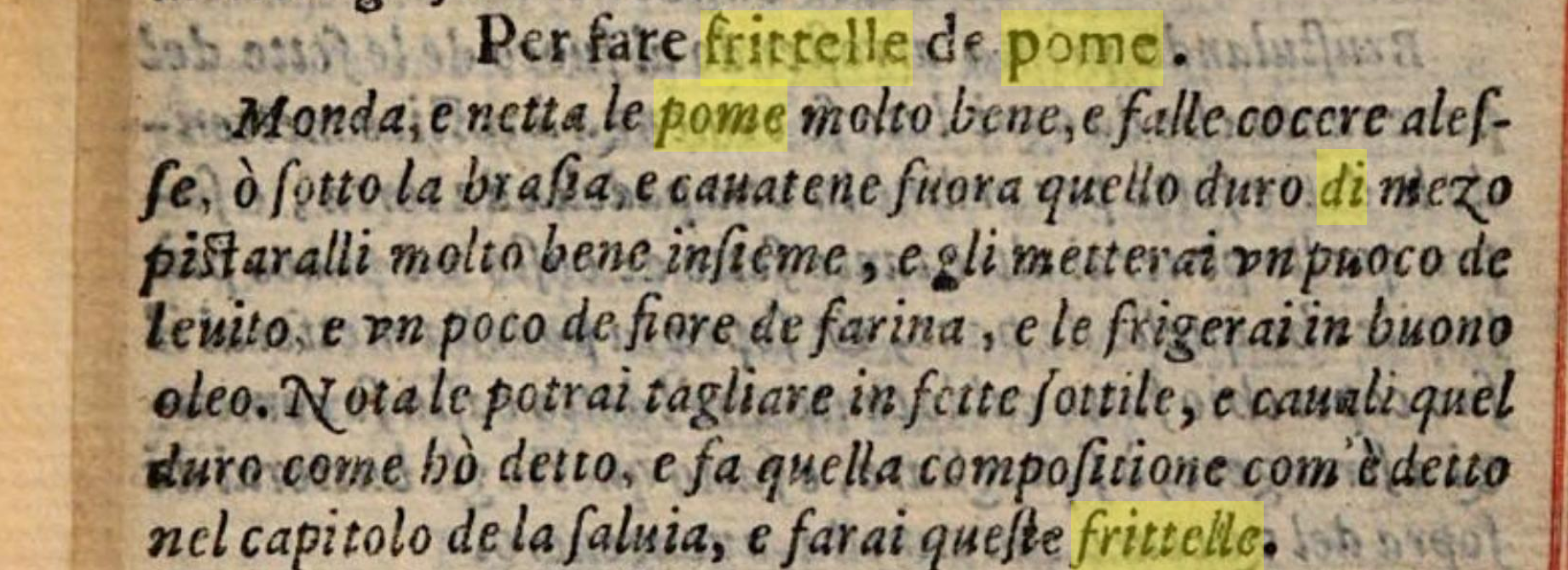

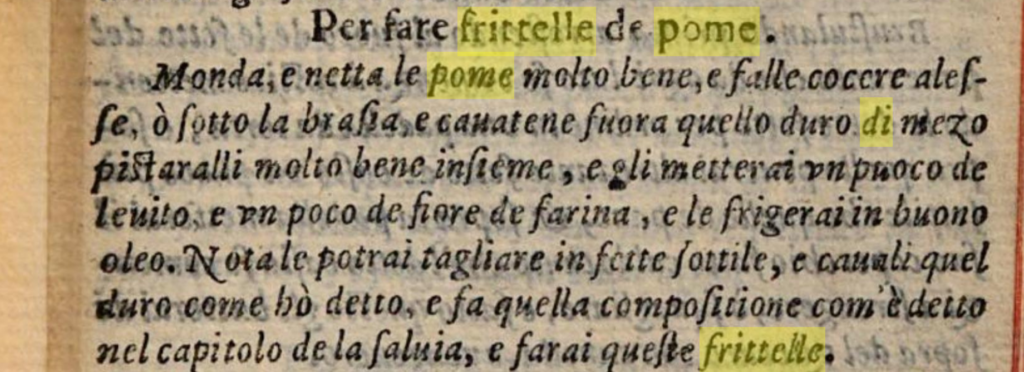

One of the most evocative early printed references appears in Epulario, il quale tratta del modo del cucinare ogni carne, uccelli & pesci d’ogni sorte (1606), attributed to Giovanni de’ Rosselli. The book, widely circulated in the 16th and early 17th centuries, was one of the most famous Italian Renaissance cookbooks.

In the 1606 edition, a recipe titled “Per fare frittelle de pome”—to make apple fritters—offers a glimpse into early modern technique. The text instructs the cook to peel and cook the apples, remove the hard core, mash them finely, and mix them with a little leaven and flour before frying in good oil. The language is direct, almost conversational, revealing a kitchen grounded in practice rather than ornament.

Epulario, il quale tratta del modo del cucinare ogni carne, uccelli & pesci d’ogni sorte, Giovanni de’ Rosselli, 1606, Google Books

What stands out is the balance between simplicity and sophistication. Apples, a humble ingredient, are transformed through careful preparation and frying. The addition of leaven suggests an awareness of texture, while the instruction to fry in “buono olio” hints at quality as a defining feature. These fritters were definitely seasonal delicacies, likely prepared for festive days when indulgence was not only permitted but expected.

The survival of this recipe in a 1606 printed volume underscores how deeply embedded fritters were in everyday and celebratory cooking alike.

Fritters Across Borders: From Venice To The Adriatic

Travel east along the Adriatic coast and fritters take on a new name: Croatian fritule. Smaller than their Venetian cousins, fritule are often enriched with rum, citrus zest, and sometimes yogurt. They appear at Christmas as well as Carnival, linking winter festivities across cultures.

In Rome, Carnival brings castagnole, round fritters rolled in sugar. In Naples, zeppole arrive in March, sometimes filled with custard. In France, beignets echo the same frying tradition, while in Spain, buñuelos carry Moorish influences in their airy texture and honeyed finish.

Each variation tells a story of migration and adaptation. Ingredients shift according to climate and trade routes, but the essential act—dropping spoonfuls of batter into hot fat—remains unchanged. Fritters are culinary proof that celebration travels well.

Writers have long been captivated by these treats. Pellegrino Artusi, in his 1891 classic La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene, includes multiple fritter recipes, reflecting their ubiquity in Italian domestic life. Folklorists and travel diarists of the 19th century frequently described Carnival scenes scented with frying dough and sugar, anchoring fritters firmly within the sensory memory of place.

The Everlasting Appeal

Today, as historic recipes are rediscovered and digitized, fritters are enjoying renewed attention. Bakers experiment with heritage grains; home cooks revisit Renaissance texts; food scholars trace the evolution of frying techniques from medieval hearths to modern kitchens.

Yet the appeal of fritters remains wonderfully uncomplicated. They are communal by nature, best eaten warm, passed hand to hand, dusted generously with sugar. They mark time, signaling a fleeting season before restraint returns. And they embody continuity, connecting a 1606 apple fritter in Epulario to a paper cone of fritole bought in a Venetian campo today.

In an age of fleeting trends, fritters endure. Crisp, golden, and fragrant, they remind us that some traditions need no reinvention, only hot oil, good ingredients, and the promise of celebration.