Alcázar de Segovia, Spain, 12th century. Photo by Ángel Sanz de Andrés, CC BY-SA 4.0

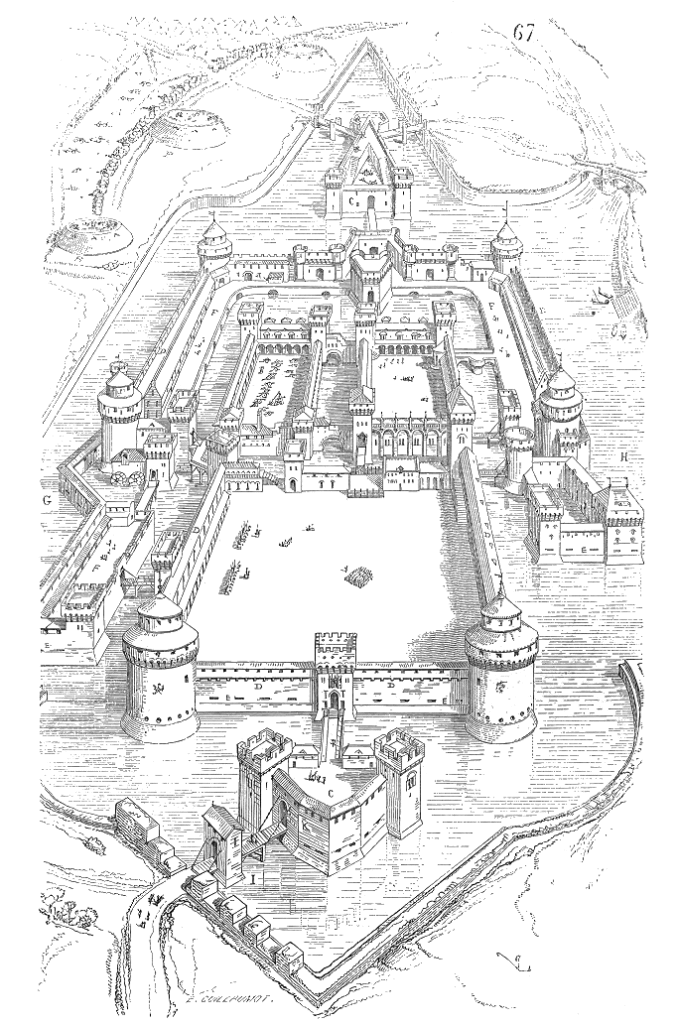

When most people imagine the Middle Ages, they picture medieval castles—stone giants rising from mist-covered hills, their battlements bristling with spears and banners. Originally built for defense, these fortifications soon evolved into architectural statements of dominance, wealth, and legitimacy. In a fragmented Europe where power was often measured by the strength of one’s walls, medieval castles became both military fortresses and instruments of propaganda—designed not merely to repel invaders, but to impress subjects, rivals, and foreign envoys.

By the 12th century, stone keeps began replacing wooden motte-and-bailey structures. The Norman lords understood the psychological weight of permanence—stone did not just defend; it endured. It told peasants and princes alike that this was not a temporary rule, but a dynasty in the making.

Walls as Power: The Political Symbolism of Fortification

Every tower and curtain wall carried meaning. A medieval castle was a carefully curated message to the world: “Power resides here.” From the Loire Valley to the Rhine, rulers invested heavily in fortifications not only for protection but for prestige. The design of a castle reflected a lord’s ambition as much as his fear.

Consider Windsor Castle in England, fortified by William the Conqueror yet transformed by successive monarchs into a symbol of royal authority that still serves the British monarchy today. Or France’s Château de Vincennes, where Louis IX ruled behind imposing towers that doubled as both palace and fortress—a living testament to divine kingship and earthly authority.

As centuries passed, the balance between functionality and grandeur shifted. Moats widened and towers grew taller, but so did the appetite for ornamentation. By the 13th and 14th centuries, medieval castles weren’t only about defending borders, but also about defining status. The stone walls that once protected life now also protected lifestyle.

Castles as Centers of Culture

Inside those fortified walls, a new culture flourished. What began as barracks and armories gradually evolved into courts of learning, music, and diplomacy. The medieval castle became the beating heart of European culture—where political alliances were forged through marriage, treaties were signed over lavish feasts, and troubadours turned noble deeds into immortal song.

The courtly ideal—refined manners, patronage of the arts, and the chivalric code—was born within these stone walls. Eleanor of Aquitaine’s court at Poitiers, for instance, became a hub of poetry and philosophy, setting standards for taste and intellect across Europe. Even as wars raged outside, medieval castles inside nurtured an early form of the Renaissance spirit—where architecture, literature, and governance intertwined.

Stone and Status

Constructing a medieval castle was not merely an act of defense; it was an act of financial declaration. Building one could drain a treasury, but to own one was to command respect. Feudal lords used their castles to project both economic strength and divine favor. The greater the keep, the greater the claim to power.

Architectural innovations spread quickly through Europe, reflecting competition among elites. The concentric castles of Edward I in Wales—such as Caernarfon and Conwy—weren’t just engineering marvels. They were imperial manifestos in stone, blending Norman military precision with symbolic geometry.

In Italy, urban medieval castles like Milan’s Castello Sforzesco or Verona’s Castelvecchio became instruments of civic pride and regional identity. They announced the arrival of powerful dynasties—the Sforza, the Scaligeri—whose rule depended as much on architectural spectacle as military strength.

From Fortress to Palace: The Decline of Defense and the Rise of Display

By the late Middle Ages, the very technology that once justified the castle’s existence—stone walls and arrow slits—was being rendered obsolete by gunpowder. Cannons could tear through even the thickest walls, and lords began to favor comfort over defense. Yet rather than vanishing, medieval castles adapted.

Moats became ornamental. Gatehouses became ceremonial entrances. Courtyards opened into gardens, and thick defensive walls gave way to stained glass, frescoes, and halls of mirrors. The architecture of power shifted from protection to projection—of taste, culture, and continuity.

The medieval castle had become a palace in all but name. Its power no longer lay in its battlements but in its symbolism. Just as monarchs transitioned from feudal lords to absolute rulers, so too did castles evolve into the architectural foundations of Europe’s future royal courts—from Versailles in France to El Escorial in Spain.

Power Etched in Stone

Today, the ruins and restorations of medieval castles across Europe still speak the language of authority. They draw millions of visitors annually—not because they promise safety, but because they whisper of ambition, legacy, and grandeur.

Their evolution—from pragmatic strongholds to artistic statements—mirrors Europe’s own transformation from fragmented feudalism to centralized states. In the age before parliaments and skyscrapers, castles were the architecture of politics. Their towers cast both literal and symbolic shadows over medieval life, shaping the visual identity of power for centuries to come.

In every crumbling keep and restored palace lies a message from the Middle Ages: true power is not just held—it’s built, displayed, and immortalized in stone.

One thought on “Medieval Castles and the Culture of Authority”