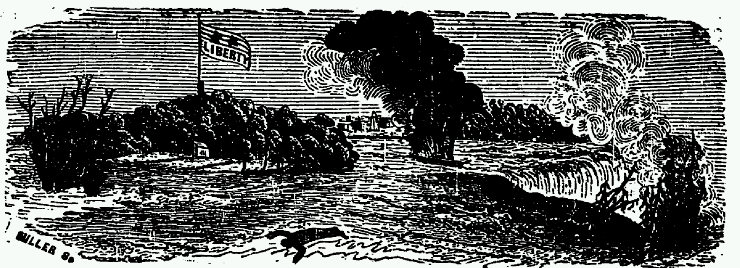

The Destruction of the Caroline by George Tattersall

In 1837 former Toronto mayor William Lyon Mackenzie organized an insurrection among the farmers of Ontario in an attempt to wrest political control over Canada from colonial authorities. The rebellion received substantial sympathy and support from Americans living in the border region – particularly around the city of Buffalo – which used a local American ship the SS Caroline to ferry weapons and supplies over the Niagara River. When Mackenzie’s forces were defeated by loyalist soldiers and volunteers in early December of 1837, they fled to Navy Island and aboard the Caroline declared the Republic of Canada. On December 29, a royal Canadian unit seized the Caroline while moored on the U.S. side of the river (at Schlosser’s Landing) killing American Amos Durfee and wounding several others. After that, they set fire to the ship and sent it over Niagara Falls.

“War with England… unavoidable”

Americans were outraged. New York Governor William Marcy sent a message to the state legislature proclaiming the “territory of this state has been invaded, and some of our citizens murdered, by an armed force, from the Province of Upper Canada.” The New York Daily Herald concluded that “War with England, seems almost now to be unavoidable.”[1]

Americans from Detroit to Buffalo began organizing and coordinating with the rebels to invade Canada. On January 5, President Martin Van Buren issued a statement “to prevent any unlawful interference” by U.S. citizens in the conflict, and urged “insurgents” organized on U.S. soil supporting the rebellion to respect neutrality laws and “return peaceably to their respective homes…” To help enforce Van Buren’s policy and prevent escalation of cross-border violence, General Winfield Scott was ordered to the Niagara frontier.[2] London newspapers closely followed the news to gauge American sentiment: “People, in expectation of a battle, had assembled… The excitement here is great. Curses, not loud, but deep, greet you on every side. Men do not huzza – they grit their teeth, and talk of vengeance!”[3]

Patriot War and Border Demarcation

Despite U.S. authorities’ efforts to stymie violence several incidents occurred in 1838. In addition, secret organizations supporting the rebels called “Hunters’ Lodges” were established along the un-delineated border stretching from Vermont to Michigan in places such as Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Detroit. According to the historian Andrew Bonthius, the “bi-national Patriot movement” has been underappreciated as it required considerable cooperation between the Anglo-American governments to avoid war: “Combined with other simmering border disputes in the northeast, periodic Patriot filibustering posed the question of war between the US and Britain, ultimately compelling the two nations to coordinate diplomatic and military efforts to suppress the movement.”[4] Border raids continued and prisoners were “taken at the Schooner Anne, Pelee Island, Short Hills, St. Clair River, the Battle of the Windmill and the Battle of Windsor….” Several rebel leaders were hung. In 1839, seventy-nine Canadian men were “convicted of treasonable practices” and put aboard the H.M.S. Buffalo and sent to Hobart, Tasmania. Others followed.[5] Fighting also broke out in northern Maine along the border with New Brunswick – prompting officials to push for a demarcation of the long border. Mackenzie was briefly jailed in New York but due to widespread support from the American public, was pardoned by Van Buren in 1840 and became a U.S. citizen. In 1842 the Webster-Ashburton Treaty delineated the vast U.S.-Canadian border (until Minnesota/Ontario) and settled the Caroline issue. In 1844 more talk of an Anglo-American war arose, but cooler heads prevailed. In 1849, Mackenzie received amnesty by the Canadian Legislature and returned home.

[1] New York Daily Herald, January 5, 1838. Letter from Marcy (Albany) dated January 2, 1838.

[2] Baltimore Sun, January 8, 1838.

[3] The Observer, London, February 4, 1838.

[4] Andrew Bonthius, “The Patriot War of 1837-1838: Locofocoism with a Gun?” Labour/Le Travail 52 (2003), 10. See: Oscar A. Kinchen, The Rise and Fall of the Patriot Hunters (New York: Bookman Associates, 1956), 37. “One of the most active in the organization of lodges along the lake frontier was Orrin Scott, a nephew of General Winfield Scott…”

[5] J. C. Carter, “One Way Ticket to a Penal Colony: North American Political Prisoners in Van Diemen’s Land,” Ontario History 101, No. 2 (Autumn 2009), 191-2.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.