Representation of La Pedrada, Andrés Castro overthrowing American filibuster invaders in the Battle of San Jacinto during the War of 1856 in Nicaragua, oil on canvas painting by Luis Vergara Ahumada, CC BY-SA 3.0.

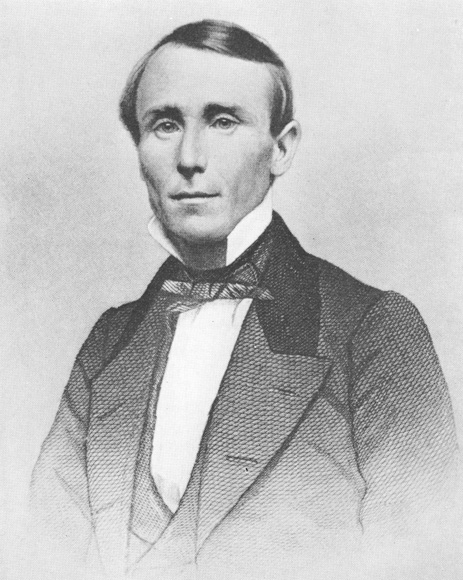

Some people called William Walker the “Grey-eyed man of destiny,” but as John E. Norvell evinces in a New York Times report October 5, 1860, there was nothing romantic about the way Walker died:

“He marched from his cell to the place of execution with a steady step and unshaken mien. A chair had been placed for him with its back towards the Castle. Having taken his seat, he was blindfolded. Three soldiers stepped forward to within twenty feet of him and discharged their muskets. The balls entered his body, and he leaned a little forward; but, it being observed he was not dead, a fourth soldier mercifully advanced so close to the suffering man that the muzzle of the musket almost touched his forehead, and being there discharged, scattered his brains and skull to the winds. Thus ends the life of the “Gray-eyed man of Destiny.”[1]

Between 1853 and 1860 American readers were captivated with Walker’s exploits and expeditions in Latin America. Born in 1824, Walker, who graduated summa cum laud at the age of fourteen from the University of Nashville, tried his hand at respectable professions such as medicine and law, but ended up as the embodiment of a mercenary movement to extend the realm of American empire south of the Mexican border. Beginning in 1853, Walker attempted to establish a republican-inspired American colony in the northern Mexican state of Sonora, briefly captured the city of La Paz in Baja declaring it the “Republic of Lower California” with himself as president, was forced to retreat back into the United States, was indicted in San Diego for violating the 1794 neutrality act, and quickly acquitted by a federal grand jury of his peers. Although Walker’s ambitions were thwarted by the Mexican government, his American supporters undoubtedly inspired him to return to fight another day. The Athens Post of Tennessee gleefully reprinted a romantic account of the ordeal from a Stockton newspaper:

“The New Republic is a Great Fact. We quite relish the audacity of William Walker. His very rashness is charming, Veni! Vidi! vici! – all in one breath. He lands his forces, fights a battle, takes two Governors prisoners, establishes a government… jumps a century in advance even of Christendom in his commercial policy, […] Hurra for Young America and annexation! The extension of the area of freedom, and filibustering generally… from 54 40 down to Patagonia and Terra [sic] del Fuego. […] Captain Walker, no President Walker, is the very Prince of Fillibusteroes, and we hope he may die with his feet on the ground. Ye gods, what peoples!”[2]

Invasion of Nicaragua and Death in Honduras

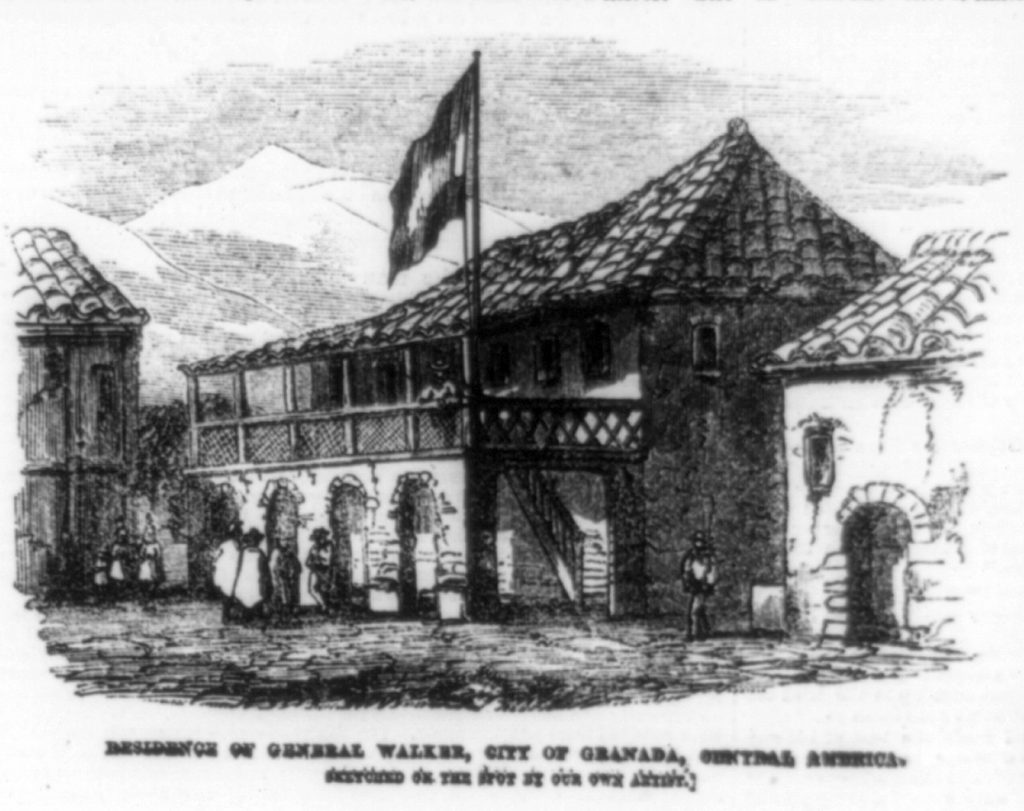

Not content, in late 1854 Walker was invited to Nicaragua by the conservative leader of a civil war faction. At the time, there were rumors that Santa Anna of Mexico was attempting “to realize the dream of Iturbide, and to make Central America a dependency of his proposed new empire.”[3] This was merely sensational speculation, but the geopolitical intrigue gave Walker and his cadre of nearly sixty charismatic adventurers an incentive to act. The “American Phalanx” expedition – as it was called – left San Francisco and arrived in Nicaragua ready to do battle. On September 3 Walker’s forces – reinforced with other supporters – routed the opposition at the Battle of La Virgin. The following month the American-led mercenaries took the capital of Granada. In July of 1856 Walker became the president of Nicaragua.

Soon after, President Franklin Pierce recognized the Walker government. These accounts were published in his own flourished version of events, The War in Nicaragua, the year of his death: “In the evening the musicians came to sing songs in praise of American valor, and… poured forth the sonorous sounds of Castilian verse in glory of the strangers who had delivered Nicaragua from the oppressions of her enemies.”[4]

Despite receiving support from the American president, Walker’s grip on Nicaragua was tenuous at best. The Tennessee adventurer-turned dictator also reinstated slavery hoping it would induce other like-minded immigrants from the United States – which inversely undermined his position among other political leaders in Central America. Adding to his problems, Walker ran afoul of powerful New York-based shipping interests that were using Nicaragua for transit to California and other west coast ports, and Walker was ousted by a combined Central American force in 1857.[5] Back in the U.S., the former president published his book and plotted to reclaim what he had conquered. In 1860, Walker landed in Honduras, was promptly captured by authorities in Trujillo, and executed on September 12, 1860.

The Silent Treatment: A Legacy in a Nation Divided

Obituaries regarding the death of William Walker were emblematic of the growing sectional divide within the United States, but not in the way one might imagine. “Walker died with remarkable fortitude.” – reported the Daily Exchange of Baltimore. The New Orleans Delta wrote that “General Walker may have been a deluded man; he certainly was an enthusiast; and having failed, will be considered a fanatic; but a more sincere, earnest, truthful, and fearless man never looked death in the face.”

One of Walker’s hometown newspapers in Nashville reprinted a report calling him a “brave commander…” In contrast, in the north, where Walker’s most vocal detractors resided, there were few expressions of glee or gloating, but also a noticeable lack of praise or romantic analogies. The Chicago Tribune reported that James Walker, the father of the thirty-six-year-old “‘grey eyed-man of destiny,’ is now on a visit to Louisville, Ky. While there he received the intelligence of his son’s execution by Honduras authorities.”[6] Walker was buried in Trujillo’s Old Cemetery, where he remains today.

[1] John E. Norvell, “How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857”, Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy & History 25, no. 4 (Spring 2012), 149.

[2] The Athens Post (Athens, TN), January 20, 1854. From the Stockton Republican (CA), Dec. 10, 1853.

[3] New York Daily Herald, March 15, 1854.

[4] William Walker, The War in Nicaragua (Mobile, New York: S.W. Goetzel & Co., 1860), 218.

[5] See: William Oscar Scroggs, “William Walker and the Steamship Corporation in Nicaragua.” The American Historical Review 10, no. 4 (1905): 792–811.

[6] The Daily Exchange (Baltimore), October 5, 1860; Louisville Daily Courier (Kentucky), October 10, 1860. Via New Orleans Delta; Nashville Union and American, October 2, 1860. Via New Orleans Delta, Sept. 28; Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1860.