“Attack on New Ulm” by Anton Gág, 1904

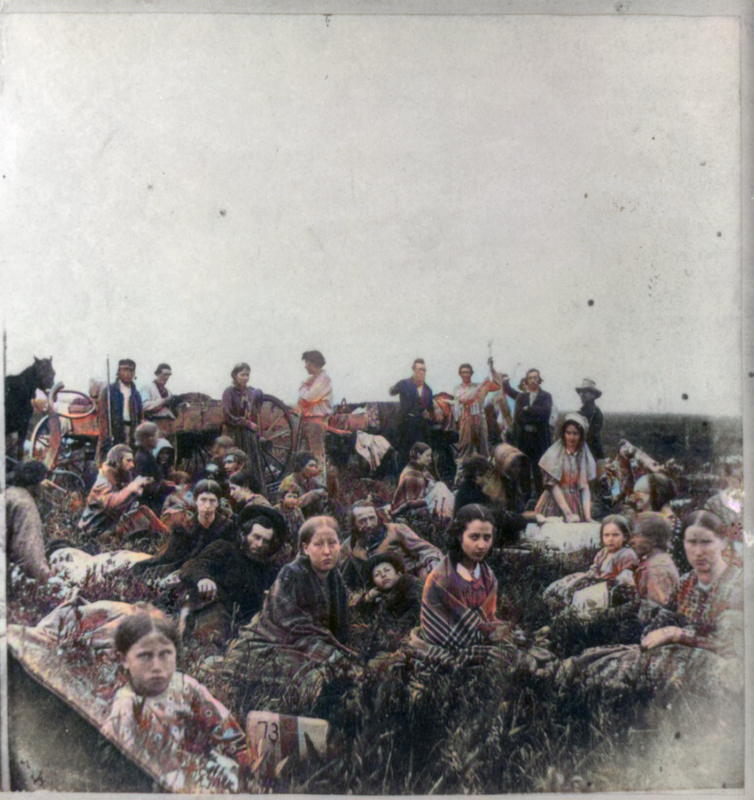

In the late summer of 1862, during the U.S. Civil War, a cadre of Dakota Indian warriors – known among their enemies as “Sioux” – forsook a life of farming and coexistence with settlers in the Minnesota River valley by sparking an uprising among the tribal bands living on nearby reservations abutting the river. The ensuing violence and murder of hundreds of farmers and their families caused widespread hysteria. Hundreds of hostages, mostly women and children, were taken. Others committed suicide rather than be captured. Lieutenant Governor Ignatius Donnelly, who accompanied an expedition to assess the emergency, reported that “You can hardly conceive of the panic existing along the valley.”

Indeed, as the expedition moved south from the new state capital of St. Paul the group observed thousands of refugees flooding the roads for the safety of larger towns. The small western settlement of New Ulm, which hosted a modest fort and garrison, was sieged for nearly two weeks before reinforcements arrived in late August to escort people out. To repay their suffering, when the remaining townspeople were evacuated to the community of Mankato, “all the strychnine in the place was put into some whiskey, which was left there for Indian consumption.”[1]

Jean LaRue’s Mysterious Disappearance

Nearby in the township of Owatonna, on a farm owned by Edward Gleek, worked a servant named Jean LaRue. LaRue had come from the Bouches-du-Rhone department of southern France and evidently left his home and mother Suzanne in search of a new life on the frontier prairie of southern Minnesota. On August 30, during the height of the uprising, LaRue was on Gleek’s farm and heard gunfire, which made him believe Indians were fast approaching. In fact, the sound of shooting came from “a boat load of soldiers on their way up the Minnesota river from St. Paul to New Ulm…” Apparently, the soldiers had “foolishly discharged their muskets many times as they steamed up the river from Henderson, carrying terror to the hearts of people among the river who were already about to flee from the dreaded Indians.” According to Gleek, LaRue also thought his life was in danger and lost his “reason from fear…” The Frenchman rushed into the farmhouse, grabbed his rifle, bullet pouch, powder horn, some other belongings, and the $783.50 he had diligently saved. After that, he ran into the nearby woods and was never seen or heard from again.[2]

By the end of September of 1862 federal authorities and state militia had put down the rebellion. Some of the uprising’s participants were captured and jailed in Mankato but a handful fled north to Canada to avoid the retribution demanded by the settlers and locals:

The citizens of Mankato and New Ulm, indignant and disgusted at the tardy movements of the Government in dealing out justice to the savage wretches who had but recently rioted in the blood of their friends and relations, attempted to break the jail at Mankato, and take the matter into their own hands. They were prevented by military force, but it is a warning to the Government that this is no child’s play.[3]

In the end, 38 Dakota were sentenced to death by hanging on a large scaffold hewn for the occasion, but Jean LaRue’s mother most likely died without knowing what had ultimately happened to her son – and must have assumed he was one of the many victims cut down by the marauding Sioux.

“Diary Tells the Story”

Nearly fifty years later in the early summer of 1919, as American soldiers returned home from war in Europe, workers for Mr. Gleek, who was by that time quite elderly, made a “startling discovery” while clearing a wooded area of his farm:

In clearing a piece of land it became necessary to cut down a gigantic white oak tree, which broke in falling, disclosing the fact that it was hollow for a distance of about fifteen feet above the ground and the cavity ending in a large opening concealed among the branches of the lower side of the tree, which leaned considerably. Within this hollow was found by the horrified choppers the mummified body of a man, not at all decayed, but dried and shriveled by the lapse of time into something rivaling the best Egyptian art. Mr. Gleek, on being summoned by the frightened laborers, recognized at once in the mummy the body of Jean La Rue…[4]

According to a local newspaper LaRue “must have known of this hollow tree, sought to his safety there, slipped down too far, and being unable to extricate himself, must have perished there where his body, preserved in the living oak, failed to decay.” Thus, LaRue was felled by his own fear and imagination, and became the victim of that which he mistakenly believed would protect him. The Frenchman who had abandoned his homeland for benign adventure on the Minnesota prairie, also left a diary “which Mr. Gleek says La Rue always faithfully kept…” The diary entry after August 29, 1862, was undated and penned in a “trembling” script: “Can not get out; surely must die. If ever found, send me and all my money to my mother, Madam Suzanne La Rue, near Tarascon, in the province of Bouches Du Rhone, France.”[5]

[1] The Manitowoc Pilot (Wisconsin), September 5, 1862. See: Charles S. Bryant, A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians in Minnesota (Cincinnati: Rickey & Carroll Publishers, 1864); Isaac V.D. Heard, History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863 (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1865).

[2] Mankato Free Press, June 21, 1919. “Body Found in Tree”

[3] The Goodhue Volunteer (Redwing, MN), December 10, 1862.

[4] Mankato Free Press, June 21, 1919.

[5] Ibid.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

I don’t know where you got your information Mr Swenson but Owatonna is nowhere near the Minnesota River ,,it’s about 40 miles away so Mr LaRue in no way at all could have heard somebody coming up the river firing a rifles .

just thought I would make a correction there for you .

The information was from a June 21, 1919, article titled, “Body Found in Tree,” in the Mankato Free Press. I guess you’d have to take up your argument with Mr. Gleek. Something scared LaRue into that tree and if it wasn’t gunfire, as the article claimed, then it was something else. Since I’m from Mankato and know the area (Owatonna township was larger in those days), I thought that was interesting as well. Thanks for reading.