Claude Duval, a French highwayman in Restoration England on the painting by William Powell Frith, 1860

Long thin rapiers. Razor-sharp. Elegant (black or white) waistcoat. Sassy adventurer and damsel in distress. Danger. Challenge. Adrenaline. These alluring motifs can easily capture your imagination if you are an adventure lover. Today, there are dozens and dozens of stories and movies about early 19th century adventures. From today’s perspective, the early 1800’s could seem like a distant era and another world, challenging with a certain dose of danger. But, for people living in the Age of Romanticism, this era wasn’t so attractive. They preferred more escaping to other, medieval, or early modern age realms, at least in books. Therefore, it’s no wonder why folk tales, as with novels and stories based on folk-tales, were so popular. So, why was the figure of the bandit or highwayman so popular? Well, these were different times, and as any time shapes the tastes and preferences of the individual, so did the Age of Romanticism.

Gazers lost in thoughts

If you take a look at the art during the Age of Romanticism, you’ll probably remember some of the most famous paintings, those of people gazing at the distance, completely lost in thought. For example, in the painting by Caspar David Friedrich, a man gazing at the distance, returned to nature, completely alone is contemplating at the ruins, representing in that way the whole generation.

Young people, thinkers who didn’t find their world very attractive. They noticed their world changed too fast and didn’t like the “brave new world.” Therefore, they decided to find the comfort in escaping. That was possible primarily through art – literature, painting, performing arts… In other words, medieval architecture, medieval art, medieval values… They found inspiration in bygone eras. The modern was too much for a “tormented and disappointed soul.” Therefore, as today’s young people often find their idols in celebrities or other famous people, it’s interesting how the young people of the Age of Romanticism often idolized outlaws, highwaymen, bandits and similar figures by researching numerous folk-tales and by creating literary and other works of art inspired by these old stories.

These stories were usually far from the real life of the bandits. 19th century writers idolized them by making them noble heroes who vanished a long time ago. They had a great life, fought for the noble cause, followed certain values… Everything that their time “lacked.” So, the popularity of the “noble bandit” started to rise.

Travelling in the character of a gentleman, Robin arrives at a beautiful villa, near Taunton Bridge in Yorkshire, where he observes an old gentleman walking in the pleasure grounds. Robin enquired at the porter’s lodge, if strangers of respectability were permitted to view the grounds; being answered as he wished, he alighted, and giving his horse to the gardener to hold, followed the walk on which he had observed the proprietor. They soon met, and Robin made a polite apology for his intrusion; upon which the gentleman assured him he was heartily welcome, and that he would himself shew the policies. Having arrived at a quiet and sequestered walk, “Sir,” says Robin, “I hear you are extremely charitable, and I must make bold to borrow the money you have upon you, as travelling in this country is so very expensive.” The gentleman looked very foolish, but resistance was in vain, and he resigned his gold. “Now,” says Robin, “you must have a binding obligation of me for the security of your money.” This the other thought somewhat honourable, until he discovered that Robin insisted on tying him to a tree: Wishing the gentleman good evening, he assured him he would find him honourable, and that “ he would not break the ties under which he was bound.” He gave the gardener a crown, mounted hishorse, and left the stranger to reflect upon the stability of his security.

Romantic representation

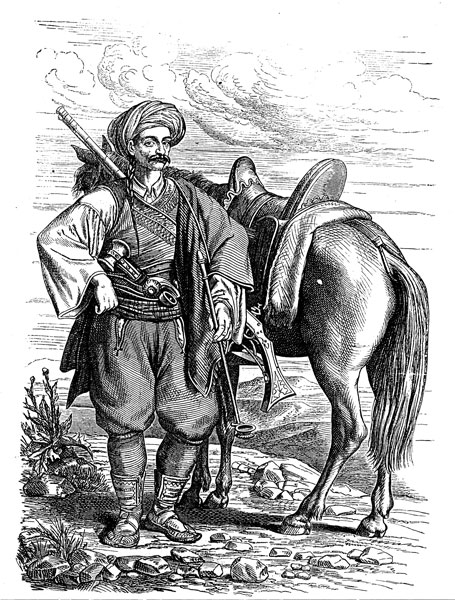

Simply stated, the Age of Romanticism was the period when many young people tried to be someone they admired. And that someone was usually a person (or a character) from the past. Outside appearance wasn’t so appreciated as virtues like nobility, higher ideals, fight for the cause like justice, love, home… Even the outside characteristics like physical strength “were in service” of the character. Therefore, it’s completely understandable why, for example, all those portraits from the early 1800s show brave warriors of extreme physical strength going against wind, against man, against destiny. Realistic people weren’t so popular. The idea was popular, something they wanted to be. Therefore, folk tales about defenders of poor people, mysterious fighters for justice, Uskoks, Haiduks and others were a source of endless inspiration.

Noble outlaws and their lifestyle became an ideal this generation tried to reach. If we look from today’s perspective, many of these outlaws had questionable moral qualities, but early 19th century “fashion” was different and they had a “different image.” So, it wasn’t hard to find yourself in these “old heroes who don’t exist anymore.”

Ideal instead of reality

During the Age of Romanticism, ideals were something young people appreciated. Reality was something harsh, ordinary, and even low for a creature like man, like an individual. Apart from fighting for the cause, the favorite folktale heroes had everything the generation of Romanticism craved – they believed in something, they lived in harmony with nature, were fearless, had a strong character… And also, they were tormented. Just as were the people of this age.

That eternal suffering that cannot be overcome made these characters heroes that everyone viewed with compassion. So, young people during the Age of Romanticism found themselves in that “eternal suffering” and they could identify with everything these folktale heroes and outlaws had.

In history, outlaws had their place and role in a certain era and context. Their lifestyle was a kind of alternative lifestyle to that of common people. Mystery, adventure, danger and everything else that belonged to their lifestyle fired the spirit and the imagination of early 19th century young person. That’s why the often harsh image of the outlaw lifestyle was often beautified so much that it resembled more the “tormented souls of the contemporary era” than to real life historical people. Therefore, bandit and outlaw folktales and stories were a sweet escapism, but also a beautified ideal that was impossible to reach.