King Sverre crossing the mountains of Voss. Artwork by Peter Nicolai Arbo, 1862

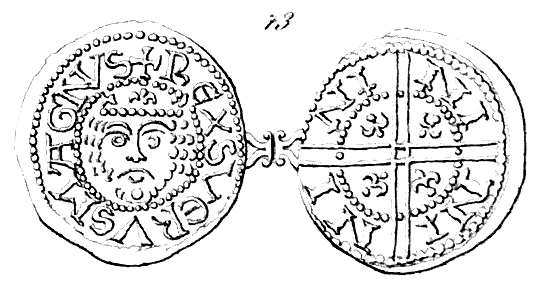

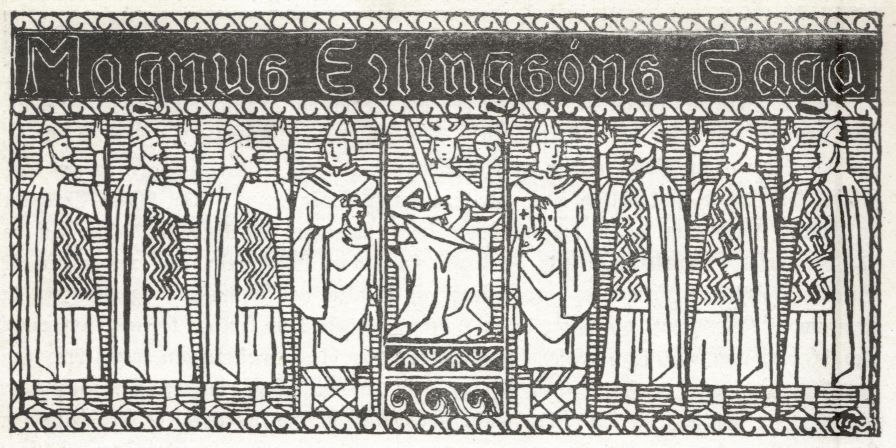

Around the year 1175, when Sverre Sigurdsson learned he was the son of King Sigurd (II) Munn, he left the Faroes where he was raised and returned to the land of his birth. Twenty years earlier, in 1155, Sigurd was murdered by his brother – an act sparking a major blood feud known as The Brothers’ War. This fraternal conflict intensified an ongoing civil war in Norway following the death of the powerful King Sigurd the Crusader in 1130. To take the crown from King Magnus Erlingson, the figurehead on the throne directed by his influential father and regent, Earl Erling Skakke, Sverre aligned himself with a small but tenacious rebel faction known as the ‘Birkebeiner’ (literally: “birch bones” or “birch legs”) – men of humble rank from the highlands of the Norwegian-Swedish borderlands with little to lose and who allegedly wore leggings made from birch bark. According to the Heimskringla, “They were a hardy people, and the boldest of men under arms; but wild, and going forward madly when they had a strong force.”[1] In the Sverres Saga, written around 1179 under Sverre’s direction by the Icelandic abbot Karl Jonsson, when Sverre arrived in Norway he cautiously surveyed the political landscape and sailed to Tunsberg, where “he was regularly in conversation with Erling jarl [Skakke] himself, and was so hidden from him that the earl did not know what Sverre had in mind or who he was.” Because Sverre appeared as a simple commoner, Erling Skakke revealed much about himself and the way he ruled Norway:

He [Sverre] was often with hirdmaend [bodyguards] or other kongsmaend [court men] and was so happy between them that they thought it was old-fashioned and funny every moment he talked to them. And by his conversation and his wisdom he asked them thus, that he got to know from them many things, which they would not have revealed, if they had known who had been there or with whom they had spoken, for the common people were somewhat ambiguous in their wording, for no one suspected his words, and no one knew what he had in mind.[2]

Birkebeiner Alliance

Sverre then went east into the borderlands to win the support of Earl Birger Brosa, who was also involved in a civil war plaguing the Swedish throne. Birger Brosa, who had married Sigurd Munn’s sister Brigit, was among many opposed to the intrigues of the Danish King Valdemar, who supported Earl Erling, and thus Birger Brosa found in Sverre an ally – regardless of whether he believed Sverre’s claims.

The Heimskringla notes that “Earl Erling was a man of great understanding and power, an excellent leader in war, and an able and prudent ruler of the country; but he had the character of being cruel and severe.” Because of this, Erling “never allowed his enemies to remain in the country, even when they prayed to him for mercy; and therefore many joined the bands which were collected against him.” For that reason, the Birkebeiner became the staunch foe of Erling and Magnus, and when they lost their leader in battle in 1177, Sverre rose to power with Birger Brosa’s blessing, and was proclaimed king later that year:

[Sverre] went to Viken, but at that time so many people flocked to him… and his men immediately wanted to give him the name of king. He excused himself, saying that it was better that his right should first be revealed by true testimony. But they said that they did not want to dwell on it, and expressed that they did not want to serve him in such a way that he did not bear a higher name than the others who followed him.[3]

Battle of Kalvskinnet, 1179

For some time afterward, Sverre and the Birkebeiners remained afoot, canvassing Norway north and south to garner support but focusing their attention upon Trøndelag – the region where the capital Nidaros (Trondheim) lay and seat of the traditional religious and political authority in Norway.

To wear down Magnus and Earl Erling, the Birkebeiners waged a war of attrition – fighting on favorable terms and raiding whenever the opportunity arose. In 1179, the Birkebeiners wintered in Nidaros, and in the spring Magnus and Erling returned to oust them from the region. Despite the rebels’ persistence, they were outnumbered, and “King Sverre and his men put out to sea… sailed and rowed, as best they could, but when King Magnus and his soldiers saw this, they pursued them as furiously as they could, both with sails and oars.” When it appeared as though the Birkebeiners would be overtaken, Sverre appealed to God to grant their escape:

But when Sverre saw that King Magnus’s ship was going much faster, and that it was carrying along with them, it seemed to him that there was no way out that could be of any use, if God did not show them his mercy beyond what seemed reasonable at the time in their case. King Sverre then lay down on his knees, called upon the holy King [Saint] Olav, and then spoke many beautiful words to his men; and at the same time a fog so thick over the sea that one could not see from one ship to the other.[4]

Divine intervention thus gave Sverre and his men an opportunity to escape unnoticed through the fog, and that spring and summer his small army lay outside Nidaros while Magnus’s army occupied the city. “Many months King Magnus’s army lay up in the city and had been drunk in the evening, because the king had kept them moving during the day, and they lay in the farms in which they had taken shelter. But when the earl heard these tidings, he got up and dressed and told the army to arm themselves.” To two forces clashed at Kalvskinnet, and “Erling was struck by a spear, which landed in the middle of his chest.” With this victory, Sverre and the Birkebeiners became masters of Trøndelag and central Norway.[5]

Mariasuden and Battle of Fimreite, 1184

With Sverre ruling from Trondheim the Birkebeiners held more legitimacy and could thus draw more resources in their war. The death of Earl Erling, the true authority of Magnus’s realm, also dealt the young king a blow, and Magnus was forced to accept aid from the Danes, who supported him with ships and men, and made forays into Sverre’s kingdom burning many of the Birkebeiners’ ships.

To offset this disadvantage, Sverre began constructing a large vessel “above the town, and it was the talk of the month that it could not be set forward without some farms being broken down, and people said that the king in this ship-building showed great recklessness and arrogance…” However, when it was finished in 1184, doubters realized…

…the king had foreseen and planned everything in such a way that the ship went forward, and it was not necessary to break houses or farms. And when the ship ran forward from the logs down into the stream, it happened in some confusion, because it had happened in the winter, when King Sverre had gone south to More, that then the ship was, however, raised… and there were nine planking gangs on each side, when the king returned. But when he saw the work, he said: “This ship is much smaller than I want it to be. Now the ship is to be cut into pieces, and it is to be laid 12 cubits to the keel.” The blacksmith spoke against it, but the king got his way… King Sverre was up in the ship when it came out on the water, and said: “God and the holy Mother Mary and the holy King Olav be praised that this ship came unharmed on the water.. as many meant and spoke unfriendly words about it against us, may God forgive them… I also want to give this ship in the trust and guardianship of the holy Mary and call it Mariasuden, and I want to ask that the holy mother Mary will be the guardian of this ship…

On June 15 the two fleets met in the long Sognefjord, near Sogndal. The Sognefjord was large and long, but also narrow, which made Mariasuden’s design ideal because it prevented Magnus’s smaller ships from flanking it, became the focus of the battle causing the enemy to panic, and forced King Magnus “overboard from his ship, and all the men who were on this ship; there the whole mass of their army was drowned..”

The rest who did not accept Sverre’s rule were slain while swimming in the sea. The Battle of Fimreite made Sverre king of all Norway. His reign, however, was marked by revolt and retribution, and thus the cycle of civil war continued for more than thirty years after his death in 1202. With the help of the Birkebeiners, his grandson, Haakon the Old, would finally put an end to the troubles – reigning more than four decades from 1217 to 1263.[6]

[1] Samuel Laing, The Heimskringla or the Sagas of the Norse Kings From the Icelandic of Snorre Sturlason, vol. 4 (New York: Scribner & Welford, 1889), 349.

[2] Gustav Storm and Alexander Bugge, ed. Norges Kongesagaer III: Sverres Saga (Kristiania: I.M. Sternersens Forlag, 1914), 7.

[3] Laing, The Heimskringla or the Sagas of the Norse Kings, vol. 4, 343; Storm and Bugge, ed. Norges Kongesagaer III: Sverres Saga, 7-13.

[4] Storm and Bugge, ed. Norges Kongesagaer III: Sverres Saga, 37.

[5] Ibid. 42-44.

[6] Ibid. 89, 103.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.