Calutron operators at their panels, in the Y-12 plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. They worked in secrecy, most having no idea to what end their labors were directed.

During World War II, amidst the tumult of global conflict, the Manhattan Project was one of the most secretive undertakings. This top-secret initiative, led by the United States, aimed to develop the atomic bomb, a weapon of unprecedented destructive power. At the heart of the project lay a web of classified operations and intense security measures, shrouding its activities in secrecy. Yet, despite these efforts, the Manhattan Project was not immune to espionage and leaks. They affected the intricate layers of secrecy and security surrounding the whole project, as well as the veil of silence surrounding it.

The Team

Led by the United States, the Manhattan Project brought together some of the world’s brightest minds in physics, chemistry, and engineering, as well as military and government leaders, to harness the power of nuclear fission for military purposes.

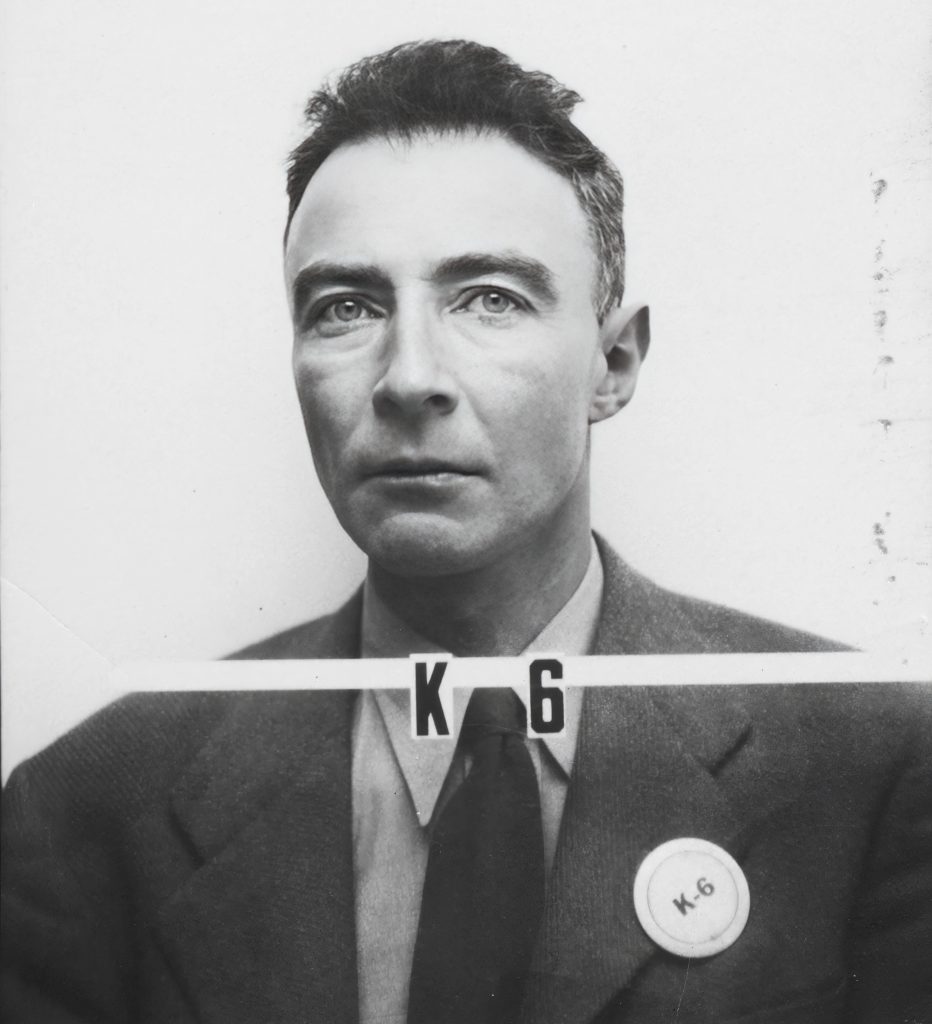

Robert Oppenheimer: Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory

J. Robert Oppenheimer, often referred to as the “father of the atomic bomb,” served as the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, the primary research and development facility for the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer was a brilliant theoretical physicist whose leadership and scientific acumen were instrumental in overseeing the design and construction of the atomic bomb. His leadership at Los Alamos earned him recognition as one of the central figures in the development of nuclear weapons.

General Leslie R. Groves: Military Director of the Manhattan Project

General Leslie R. Groves was appointed as the military director of the Manhattan Project, tasked with overseeing the project’s management, logistics, and security. A highly capable administrator with a background in engineering, Groves was responsible for coordinating the efforts of scientists, engineers, and military personnel across multiple research facilities. Under his leadership, the Manhattan Project achieved remarkable progress in a remarkably short time frame.

Enrico Fermi: Pioneer of Nuclear Reactor Technology

Enrico Fermi, an Italian-born physicist, made significant contributions to the Manhattan Project‘s efforts to develop nuclear reactors for the production of fissile material. Fermi played a key role in achieving the first controlled nuclear fission reaction in December 1942, a crucial milestone in the development of atomic weapons. His expertise in nuclear physics and reactor design laid the foundation for the production of plutonium, a critical component of the atomic bomb.

Niels Bohr: Danish Physicist and Consultant

Niels Bohr, a Danish physicist and Nobel laureate, served as a consultant to the Manhattan Project, offering insights into the theoretical and practical aspects of nuclear physics. Bohr’s collaboration with American scientists, including Oppenheimer and Fermi, facilitated the exchange of ideas and accelerated progress in atomic research. His contributions to the project helped shape the scientific understanding of nuclear reactions and reactor design.

Oppenheimer’s Scientific Team at Los Alamos

The scientific team assembled by Oppenheimer at the Los Alamos Laboratory comprised some of the brightest minds in physics, chemistry, and mathematics. Notable scientists such as Richard Feynman, Edward Teller, and Hans Bethe made significant contributions to the theoretical understanding of nuclear reactions, the design of implosion-type nuclear weapons, and the development of bomb components. Their collective expertise and innovation were essential to the success of the Manhattan Project.

Military and Industrial Partners

Beyond the scientific and technical personnel, the Manhattan Project relied on the support of military and industrial partners to achieve its objectives. Military personnel provided security, logistics, and operational support, ensuring the safety and secrecy of project operations. Industrial partners, including companies such as DuPont and General Electric, contributed expertise in engineering, manufacturing, and materials science, enabling the mass production of fissile material and bomb components.

Origins and Objectives of the Manhattan Project

The origins of the Manhattan Project can be traced back to the discovery of nuclear fission by German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938. Recognizing the immense potential of harnessing nuclear energy for military purposes, the scientific community in the United States became increasingly concerned about the prospect of Nazi Germany developing atomic weapons. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the establishment of the Manhattan Project in 1942, with the primary objective of developing an atomic bomb before the Axis powers.

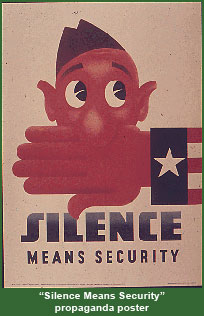

Secrecy as a Cornerstone of the Manhattan Project

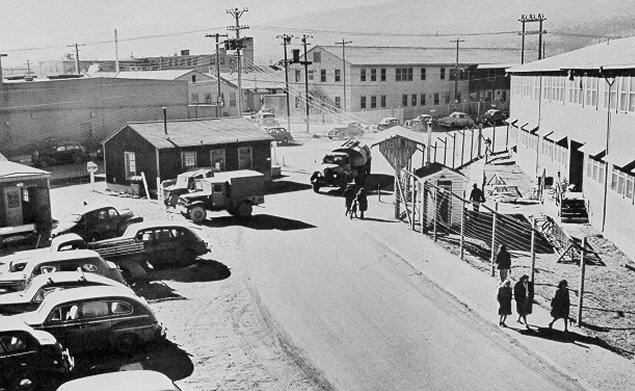

From its inception, secrecy was paramount to the success of the Manhattan Project. Under the direction of General Leslie R. Groves, the project operated under a veil of tight security, with access restricted to a select group of scientists, engineers, and military personnel. Key research facilities, including Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, Oak Ridge Reservation in Tennessee, and Hanford Site in Washington, were established in remote locations to minimize the risk of detection and espionage.

Classified Operations and Compartmentalization

Within the Manhattan Project, compartmentalization was a fundamental security measure. Each aspect of the project was divided into discrete compartments, with limited access granted on a need-to-know basis. This compartmentalization ensured that individuals only had access to information relevant to their specific tasks, minimizing the risk of unauthorized disclosure. Scientists working on the development of the bomb, for instance, were often unaware of the broader scope of the project or the identities of their colleagues.

At its core, the Manhattan Project was a project within a project, with layers of secrecy embedded within its operations. Even among those with high-level security clearances, access to certain areas and information was restricted based on the principle of strict compartmentalization. For example, scientists working on uranium enrichment at the Oak Ridge facility might have not known about the bomb’s design being developed concurrently at Los Alamos. Access to classified information within the Manhattan Project was strictly controlled, with clearance levels assigned based on an individual’s specific duties and responsibilities. Scientists, engineers, and military personnel were granted varying levels of clearance, depending on their involvement in the project. Clearance levels were regularly reviewed and updated to ensure that access remained commensurate with the individual’s role and the sensitivity of the information involved.

Physical and Informational Barriers

Physical barriers, such as restricted areas, guarded facilities, and secure storage facilities, played a crucial role in safeguarding classified information within the Manhattan Project. Access to sensitive sites was strictly controlled, with perimeter defenses, identification checks, and surveillance measures employed to prevent unauthorized entry. Furthermore, classified documents and data were stored in secure locations, protected by encryption, locks, and other security measures.

Consequences of Violating Security Protocols

The consequences of violating security protocols within the Manhattan Project were severe, ranging from loss of security clearance and dismissal from the project to criminal prosecution and imprisonment. Security breaches were rigorously investigated by project security personnel and could result in the identification and apprehension of suspected spies or infiltrators. These measures reinforced the culture of secrecy and security within the project, impressing upon participants the gravity of their responsibilities and the importance of safeguarding classified information.

The compartmentalization of the Manhattan Project left a lasting legacy in the field of US security and intelligence. The principles of restricted access, need-to-know basis, and compartmentalization have been adopted and adapted by subsequent classified projects and intelligence agencies, shaping modern practices in safeguarding sensitive information. However, the challenges of balancing security with the need for collaboration and transparency continue to be debated, underscoring the complex nature of managing classified operations in an interconnected world.

Espionage Threats and Countermeasures

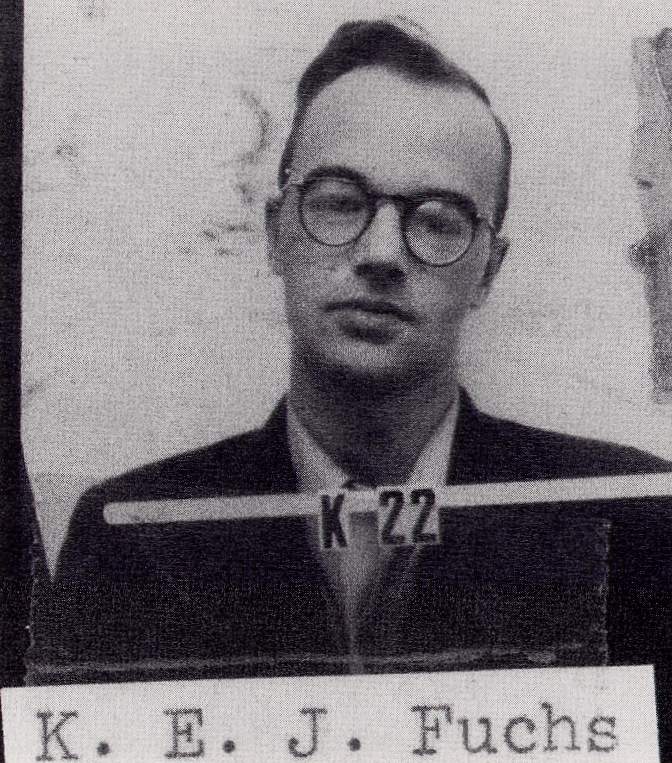

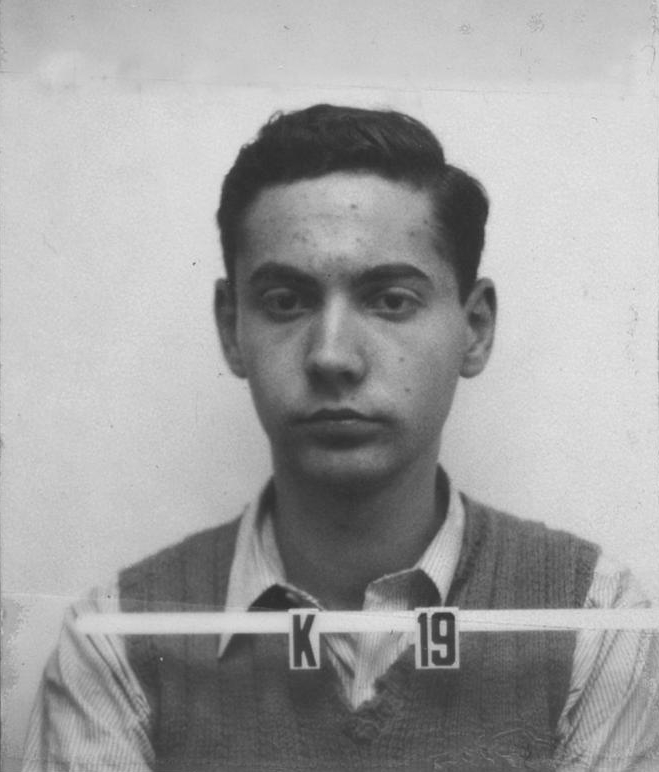

Despite the stringent security measures, the Manhattan Project faced persistent threats from espionage. Soviet spies, most notably Klaus Fuchs and Theodore Hall, infiltrated the project and transmitted valuable information about the bomb’s design and development to the Soviet Union. Fuchs, a German physicist who worked at Los Alamos, provided detailed technical drawings and calculations to Soviet intelligence agents, significantly accelerating the Soviet Union’s own atomic weapons program.

Klaus Fuchs’ and Theodore Hall’s Los Alamos security badge photos, 1944

To combat espionage threats, the Manhattan Project implemented counterintelligence measures to identify and apprehend suspected spies. The project’s security apparatus, led by Colonel Boris Pash, conducted extensive investigations and surveillance operations to root out potential infiltrators. Suspected individuals were subjected to rigorous background checks and monitoring, and in some cases, detained and interrogated.

Under Pash’s leadership, the Security Section implemented a range of counterintelligence measures aimed at identifying and neutralizing espionage threats within the Manhattan Project. These measures included:

Background Checks and Vetting

Pash and his team conducted thorough background checks on all personnel involved in the Manhattan Project, including scientists, engineers, military personnel, and support staff. These checks aimed to identify individuals with potential security risks, such as foreign ties or criminal backgrounds, and prevent them from gaining access to classified information.

Surveillance and Monitoring

The Security Section employed surveillance and monitoring techniques to identify suspicious behavior or unauthorized communications among project personnel. This included monitoring phone calls, intercepting mail, and conducting physical surveillance of individuals suspected of engaging in espionage activities.

Security Clearances and Access Control

Pash oversaw the administration of security clearances and access control procedures within the Manhattan Project. Personnel were granted varying levels of clearance based on their roles and responsibilities, with access to classified information strictly controlled and limited to individuals with a legitimate need-to-know.

Interrogations and Investigations

In cases where espionage or security breaches were suspected, Pash’s team conducted thorough investigations and interrogations to identify and apprehend suspects. Suspected individuals were subjected to intense questioning and, if necessary, detained for further investigation.

Coordination with Law Enforcement and Intelligence Agencies

Pash maintained close coordination with law enforcement agencies, such as the FBI, and intelligence agencies, such as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), to share information and collaborate on security matters related to the Manhattan Project. This collaboration enhanced the project’s ability to identify and counter-espionage threats effectively.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

The Manhattan Project‘s success in developing the atomic bomb marked a pivotal moment in human history, forever altering the course of warfare and international relations. However, it also underscored the challenges and ethical dilemmas associated with secrecy and security in scientific endeavors. The project’s legacy serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the delicate balance between national security imperatives and the preservation of scientific openness and freedom.

It is noteworthy to say that there exists extensive documentation regarding the Manhattan Project. In the latter part of 1944, General Leslie Groves, overseeing the Manhattan Engineer District, initiated the development of an extensive historical documentation known as the Manhattan District History. This comprehensive project aimed to chronicle the manifold activities and accomplishments of the Manhattan Project in a manner that could be easily grasped by the general populace.

Under the editorial guidance of Gavin Hadden, a seasoned civilian employee within the Army Corps of Engineers, a team of authors was tasked with compiling this classified history. Their objective was to provide a detailed narrative encompassing the research, design, construction, operation, and administration facets of the Manhattan Project, synthesizing vast amounts of information into a coherent and accessible format.

The volumes comprising the Manhattan District History were richly annotated and supplemented with statistical data, visual aids like charts and engineering drawings, as well as maps, photographs, and meticulously crafted indices. Despite its significance, the production of this historical documentation was limited to a select few copies.

Presently, one of these invaluable copies finds safekeeping under the custody of the Department of Energy’s Office of History and Heritage Resources, ensuring its preservation and availability for future generations to gain insights into this pivotal period of history.

The Manhattan Project stands as a testament to the extraordinary lengths to which governments will go to safeguard their most sensitive military secrets. Through a combination of stringent security measures and compartmentalization, the project succeeded in maintaining a veil of secrecy around its operations. Yet, the threat of espionage loomed large, underscoring the perennial cat-and-mouse game between intelligence agencies and foreign adversaries. The Manhattan Project is also a reminder of the enduring tensions between secrecy, security, and the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

Hi Ivana, several times Richard Feynman found himself in hot water because he was able to pick every secure lock the scientists used to store classified documents. His point was that they weren’t very secure. The security people threatened to charge him with espionage.

Thanks Michael, interesting! 🙂