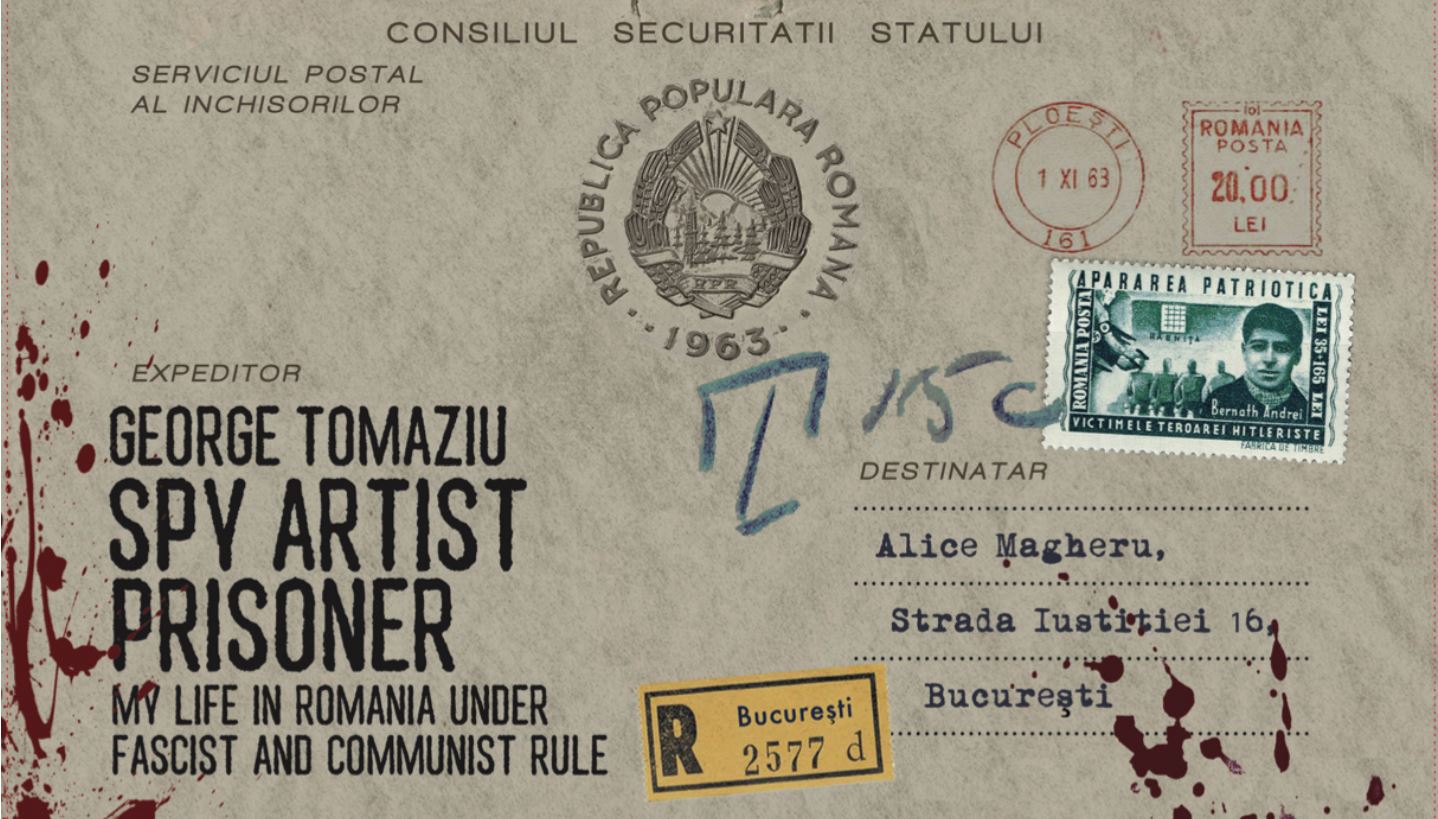

Source: EnvelopeBooks

This post is sponsored by EnvelopeBooks.

George (Gheorghe) Tomaziu was a Romanian painter, illustrator, memoirist and poet. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bucharest. During World War II, he operated as an MI6 agent. As an agent of the British Intelligence Service, he organized a secret group of collaborators that included Alexandru Balaci, Romanian italianist, literary critic and historian. During 1944, Tomaziu was arrested, beaten and placed under investigation under suspicion of espionage. The same year he was released from Malmaison prison in Bucharest.

During war, Tomaziu observed German troop movements through Romania towards the Russian front, observing, on one occasion, the mass-killing of Jews in the small Ukrainian town of Brailov. He knew he might be arrested, tortured and killed by Romania’s rightwing regime but thought that if he survived, his contribution to the war effort would be recognised. It wasn’t. After Romania turned Communist, he was sent back to prison in 1950 and kept him there for 13 years. Following his release, the British helped him get out of Romania and he settled in Paris.

The Communist Fire

The years after WWII brought a new system for the Romanian state. The Communist fire tried to “burn” everyone who didn’t comply with the new regime. Skillful in words as in other artistic works, Tomaziu describes all the things the communist regime brought in an interesting, surrealist tone that makes the reader sympathize with the reality that wasn’t surreal, but 100 percent real and definitely harsh.

“Our new master did not tolerate any show of reluctance,” says Tomaziu in Chapter 10 that speaks about the post-war years. The new government took all possible resources in collaboration with the Soviet Union, trying to create the new “democratic state where everyone will be equal.”

“I had a telephone call from the editor of the Romanian version of the Red army Journal,” explains Tomaziu. The editor didn’t give his proposition or ask politely for a review. On the contrary, he brusquely demanded Tomaziu write a review of the exhibition. Tomaziu tried to find an excuse like pressure of time or flu, but the editor just said: ”We will send for your article the day after tomorrow.”

Not having a choice, Tomaziu tried to “get away” elegantly, so he wrote about the beauty of Cyrillic letters, the richness of black print, the delightful illustrations, etc. But, the real surprise followed a day or two later. One of Tomaziu’s friends called to congratulate him on the “collaboration.” Therefore, Tomaziu sent for the article and read it in horror. The sentences he wrote were replaced with a stockpile of slogans like “the victory of Socialism,” ”glory to the heroes of popular culture,” ‘thanks to the generous example,” etc. After that, he met the editor, his friend, and demanded an explanation, throwing the money he was paid onto the editor’s desk. His friend told him he wanted to save him “from a mountain of problems.”

All the Privileges for the Party Members

Tomaziu didn’t want to fill in the application for the Party membership, although the members had all the possible privileges and avoided the drama to which “mere mortals” were exposed. Mysterious assassinations, denunciations, disappearances, suicides and starvation; all of that was everyday reality under the new regime. One day too, Tomaziu was invited to his friend’s house and by chance, found him preparing to hang himself from the ceiling because he wanted to “end everything.” It was easier to do that rather than accept something to he considered wrong. The powerlessness, inhumanity and injustice are three words that describe the feelings in post-war Romania. The best harvested wheat went from the country to the USSR and even canned food the International Red Cross brought was kept by the government and reserved for the Party members. According to Tomaziu’s words, “the rest could starve.”

The Surreal Atmosphere of Fear

The chance for escape was poor. “We seemed to be on the point of making our escape when the infamous Ana Pauker became minister of Foreign Affairs. She gave the order that any living thing approaching the frontier should be machine-gunned down,” notes Tomaziu. Therefore, there was no choice but to come back and try to live in the atmosphere of fear and anxiety, especially when it comes to secret police raids who later arrested and interrogated Tomaziu.

Tomaziu also describes that part of his life, making the book a complete view on an authoritarian regime, written by a citizen who didn’t want to sacrifice his own freedom for the system of certain norms, rules and regulations.