During the 17th century, the Franco-Ottoman relations were quite stable. The alliance, established in 1536, continued during the majority of this period. There were no large conflicts. Despite that, intelligence activity during this period was very lively. The example of Mahmut, an Ottoman spy undercover, gives us valuable information on the Ottoman international politics.

“Titus”: One Day He Went Abroad and Never Returned

Mahmut, an Ottoman spy, lived for forty five years in Paris undiscovered. This allowed him to observe all the important events in the west between 1637 and 1682, during this time he gave an impartial account to the Divan at Constantinople, of the most remarkable transactions of Europe and discovered several intrigues and secrets of the Western Courts.

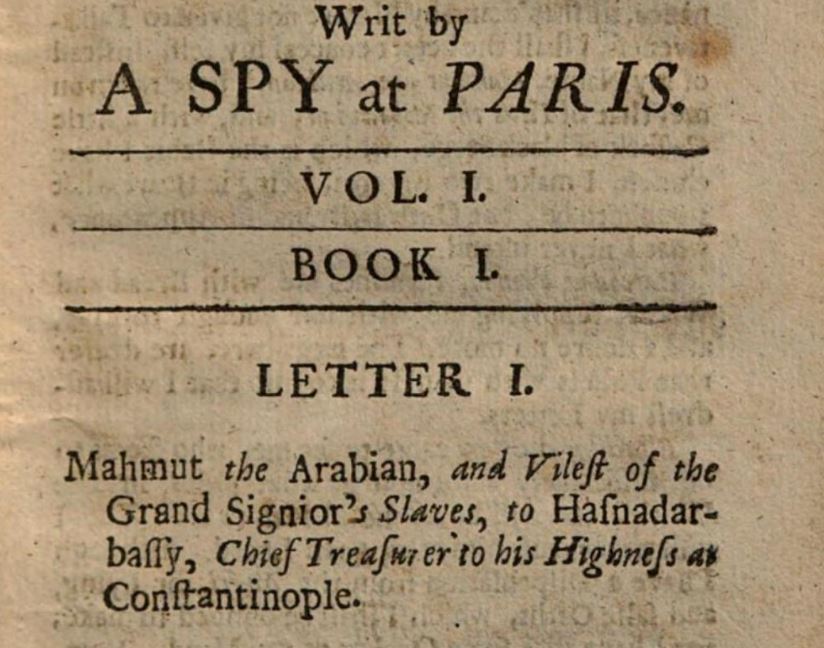

The letters were originally written at the end of the 17th century in Arabic and translated into Italian, French and English. They were revealed by an intellectual who, in the year 1682, visited Paris. By mere chance he discovered many letters written in Arabic lying in the corner of a room in the house where he stayed. The landlord of the house said that, before this visitor, a man who claimed to be a Moldavian native lived there for a long period. He was a well-educated, well-mannered man interested in science and affairs like many refined men of that era. But one day, he just went abroad and never returned.

The letters were published in a few volumes and are a very valuable resource for this era of European history.

Mission Not Impossible

Mahmut arrived in Paris on September 11, 1637. Upon his arrival, he wrote a letter to the hasnadar, a chief Ottoman treasurer. What did the life of an Ottoman spy look like in the 17th century? Mahmut reveals:

”Being but newly arrived, I scarce know any Body, and am as little known myself. I have suffered my Hair to grow a little below my Ears; and, as to my Lodging, ‘tis in the House of an Old Flemming, where my Room is so small, that Jealousie itself can scarce enter. I will have no enemy near me, I will therefore admit of no Servant.”

Therefore, upon his arrival he rented a small room and declined to have any servant near him. Of course, he couldn’t present himself as the Mahmut the Arabian, so he took a new identity – “Titus the Moldavian.” The only man who helped him was Eliachim who instructed him Western customs and behavior, but Mahmut emphasized he didn’t believe too much to this man.

”Yet I will never trusted more than I need.”

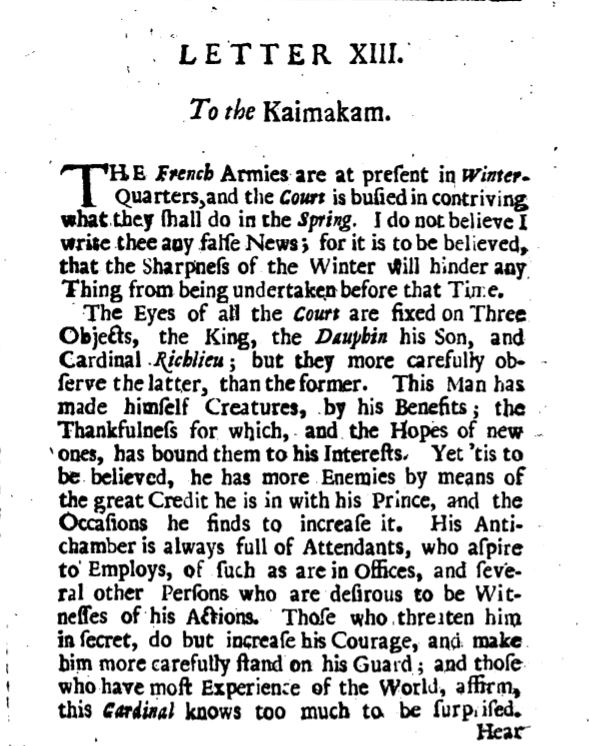

“Titus” also describes the city and the government mentioning bridges and Richelieu.

”This great City is divided by a River, and both parts of it are joined by a great Bridge of Stone, well built and very stately.”

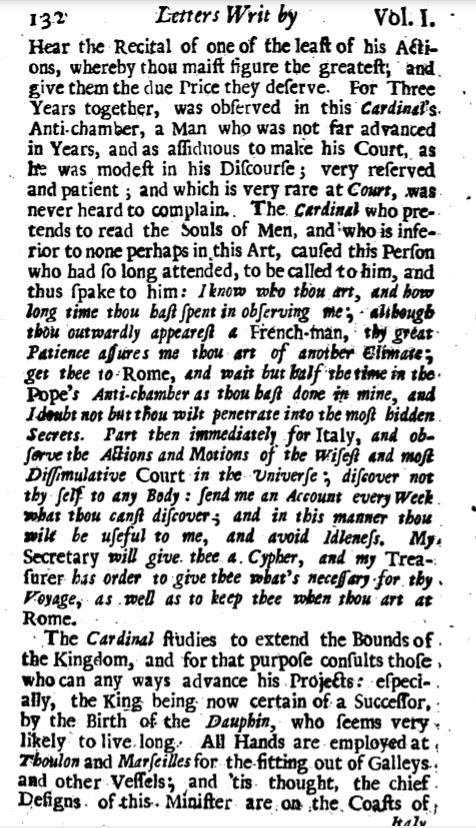

“A Church man, term’d at Rome a Cardinal, is the Principal Minister of State; his name is Armand du Plessis, Cardinal of Richelieu. He is esteem’d a great Politician, a Man of Wit and Action, and every way fitted for the Place he holds.”

After that, the Ottoman spy reveals his mission:

”I go into the Churches, as a Christian; and when I seem attentive to their Mysteries, I hold our sacred Alcoran in my Hands, adressing my Prayers to our Holy Prophet; and thus behaving myself, I give no Offence.”

So, he posed as a Christian, very calm person who minded his own business and avoided conflicts.

”I avoid Disputes, mind my own Concerns, and do nothing which may endanger my Salvation.”

Therefore, Mahmut was a loyal servant of the Ottoman court and he did nothing to endanger his cover. Regarding the 45 years of his service in Paris, “Titus the Moldavian” was one of the finest people the Ottoman court could send on a mission. His life was calm and quiet, but devoted to the cause in every aspect.

Ivana Tucak

2 thoughts on “Forty-Five Years Undercover: An Ottoman Spy in 17th Century Paris”