“I didn’t have a writing career and didn’t think in those terms. I still don’t. I’ve never really wanted a career in anything. Life’s too short and sweet for that grim, mortgage-in-the suburbs approach”, says John Fullerton, the former spy and journalist who lived and worked in 40 countries and covered a dozen wars.

Sometimes, it’s necessary to experience something to become excellent in something else. That happened to John. He has been writing since he was young, but it seems his Middle East adventures shaped that fine writer inside him.

“I wrote plays while at preparatory school. I was a boarder and I’d make up stuff, using a torch for lighting effects. It was to entertain my friends in our dormitory at night. These were simple, melodramatic murder mysteries. They evolved into three-act plays with a curtain, several parts and usually quite a political plot. This was apartheid South Africa, incidentally. My historical knowledge was poor and simplistic – the British were cast as the good guys, the Boers (Afrikaners) the bad. The plays were shown at weekends when some of us didn’t go home and I’m sure they must have been toe-curlingly awful”, says John about his writing beginnings.

The Middle East Adventure created Richard Brodick

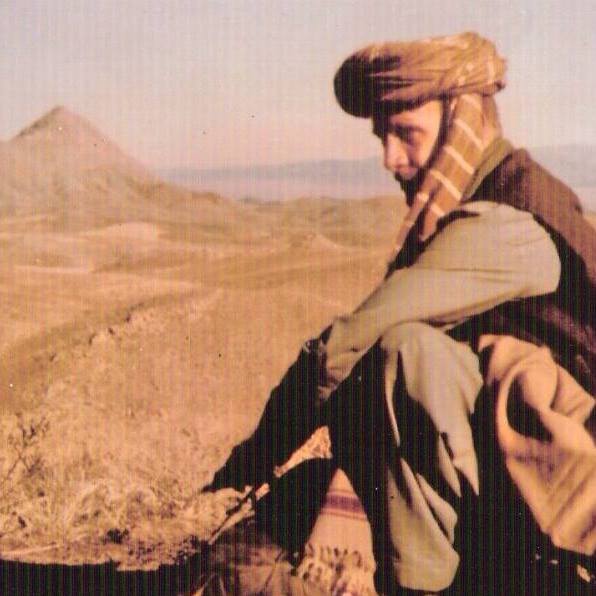

Things would become more interesting later. The Cold War took John to the Middle East. Being the head agent on the Afghan-Pakistan frontier was a dangerous and fascinating adventure.

THA: How did your work as an intelligence officer affect your writing career?

I was never an intelligence officer but what the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) calls a contract labourer. I was hired on a two-year contract. My role was that of ‘head agent’; I was the cut-out between the intelligence officers working under diplomatic cover out of a local SIS station and the sub-agents I recruited.

Right at the end, I asked if they wanted to take me on as an intelligence officer. They said they didn’t because I had a tendency to rush off and do what I thought needed doing without waiting for authorisation. They were right. They said I would probably ‘chafe under the restrictions of a peacetime service’. Right again.

I didn’t have a writing career and didn’t think in those terms. I still don’t. I’ve never really wanted a career in anything. Life’s too short and sweet for that grim, mortgage-in-the suburbs approach. My first book was a short non-fiction work, The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, which I wrote once my contract was over. I knocked it out on my beloved Olivetti portable in six weeks. I emptied my notebooks into it. It had no style, no special appeal. It was a basic guide to the Afghan conflict for journalists and diplomats new to the region in the early 1980s.

My first novel, The Monkey House, set in Sarajevo, was published in 1996.

THA: During the Cold War, you worked as a head agent on the Afghan-Pakistan frontier. How dangerous was it to work there?

Chance always plays a role. It does in the safest and most secure life. You could be in the wrong place at the wrong time, or you could do something stupid, such as stick your head above the parapet and get it blown off. Or you could be accused of being a spy, or having a price put on your head, which I had for a while, though I didn’t take it seriously. It was fun, mostly. Or you could be shot at random and for no apparent reason. Every single day was different and the people – on all sides – were fascinating.

THA: How much is the real Cold War atmosphere reflected in your novels?

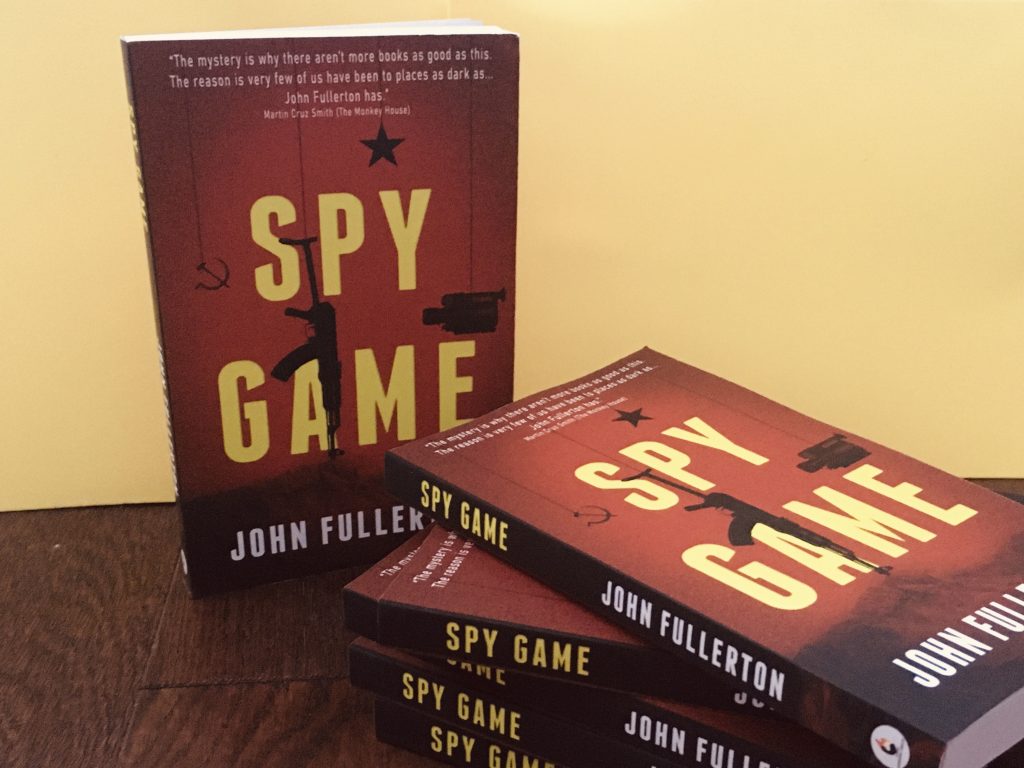

A lot in the Cold War spy trilogy, obviously, starting with Spy Game, which is very much based on my adventures on the Afghan-Pakistan frontier, and also to some extent the other two, Spy Dragon and Spy Trap. The last pair drew on my experiences in places such as Beirut which I knew as the Reuters bureau chief during part of the Lebanon war. They also introduce the reader to the Chinese foreign intelligence service, a huge and active global player today.

THA: For the younger generations who don’t remember: How would you describe the Cold War atmosphere? From your perspective? Was there something about it that affected your writing?

It coloured everything. The Soviets were seen as a very real threat, rightly or wrongly. Somehow, I welcomed it in the sense that my grandfather had fought in World War I as a cavalry officer, both parents and their siblings had done so in World War II, and it seemed only natural that I should look to the Soviet Union as a continuation of an existential challenge after the demise of the Nazis. The Soviets, it seemed to me then, were a continuation of an authoritarian trend. Which is odd, because in my last year at school I discovered Marxism, which I found really exciting – but the Soviet gerontocracy with its labour camps, secret executions and hatred for individualism filled with me dread and didn’t seem to be socialist at all.

Shoot-em-up Heroes are Predictable and Boring

As John says, there is no Hollywood glamour in the real spy life. So, he created a different character. No James Bond here.

THA: We all know the most famous fictional spy, James Bond. I presume the spy life isn’t so glamorous as in the movies? Without casinos and pretty women?

I read all the Fleming books, but to be quite honest, I didn’t like them. There was something distasteful about them, something twisted – misogynistic, sado-masochistic, and the violence mostly gratuitous. Bond was a sick, upper class wet dream. Though I can also see why they were so popular. No, sorry, real life spies don’t pick up beautiful women, carry guns or waste the taxpayers’ money on fast cars and in casinos.

THA: What do you like and dislike about fictional spies?

What I like: the characters in Geoffrey Household, Eric Ambler, Adam Hall, Len Deighton and Norman Rush novels. The cold, ruthless characters in the early Le Carre espionage novels were also well drawn.

What I don’t like: absurd, shoot-em-up heroes, all brilliant, all physically powerful, handsome or beautiful, solving intractable issues with knife, gun, esoteric poison or an improbable blow to the throat. They’re predictable and boring for the most part. There’s one outstanding exception, and that’s Luke Jennings, whose female spies provide first-rate entertainment with considerable flair. Mostly I like flawed characters, characters that change under pressure.

THA: The main character of your novels is Richard Brodick. Briefly, what would you say about him? Is he closer to James Bond or George Smiley?

Brodick begins in Spy Game as young, naive, romantic, too trusting, thoughtlessly patriotic.

In Spy Dragon he falls victim – professionally and sexually – to a more experienced, more worldly and certainly more devious Chinese intelligence officer. She recruits him under duress, then beds him; he tells his masters in London that he’s recruited her. He becomes cynical, deceitful – and ambitious. He’s neither a Bond nor a Smiley.

And at the end, you published two novels, Spy Dragon and Spy Game? When can we expect the third one – Spy Trap?

In April, hopefully. This is what it’s about:

Brodick, who now heads the SIS UK Station, works with the Chinese intelligence officer, whose work name is Fang, Mandarin for ‘fragrant’. An English businessman is reported dead in a Beijing hotel. Officially, his heart failed after a drinking binge.

Brodick knows it’s a lie. The financier is one of his most successful agents, and he doesn’t drink. His Chinese lover has poisoned him – or so it seems.

China’s future is at stake. Its veteran leader, Deng Xiaoping, believes the country will collapse if his reforms fail in the face of opposition from Communist Party hardliners.

For Brodick and Fang, it’s not just their careers but their lives on the line.

That’s it, pretty much.

THA: Thank you very much for your time and I wish you much success in 2022 and in your writing career!

Thank you for the opportunity, Ivana, and all best wishes for a safe, happy and successful year.