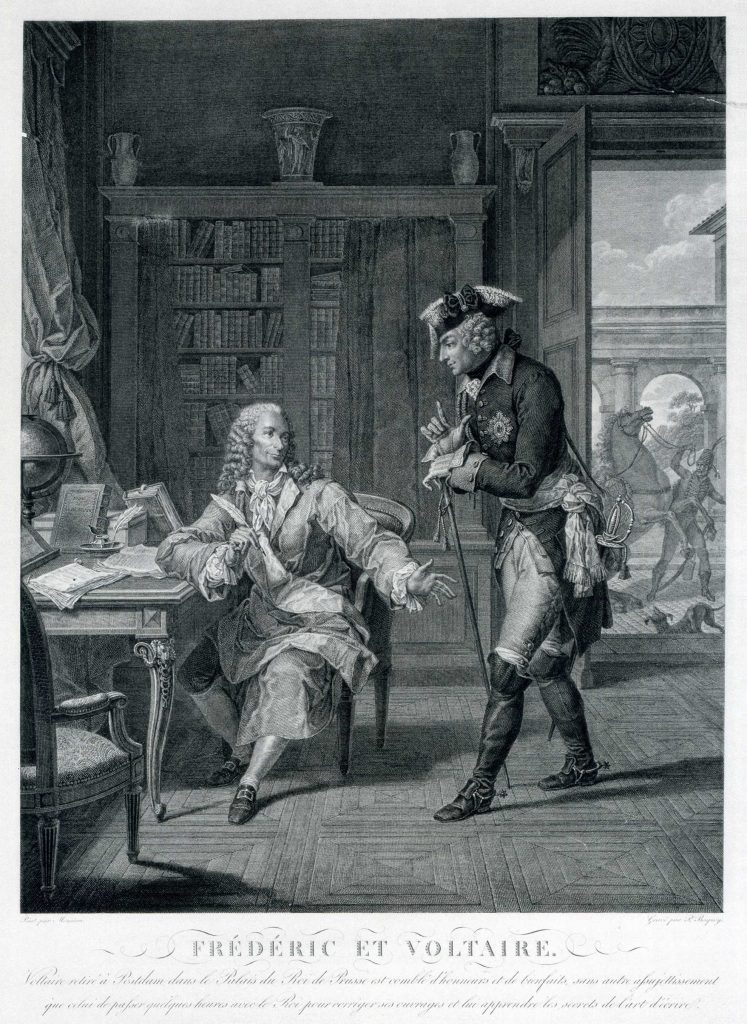

Frederick the Great, a portrait from the 1740s (by David Matthieu)

Reason, senses, liberty, progress, fraternity, toleration, constitutional government, and separation of church and state are some of the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment, or, in other words, the Age of Reason, the age that marked the 18th century. In the government of that age, there is an interesting term that lives along the idea of enlightenment, and the term is “absolutism.” Enlightenment and absolutism together explained the idea for a new form of government. That government was based on the principles of Enlightenment and that is enlightened absolutism. Enlightened monarchs claimed they rule for their subjects’ well-being and that made them different than traditional rulers. One of the rulers of Enlightened absolutism was Frederick the Great. In contrast with Niccolò Machiavelli, in his work “Anti-Machiavel,” the Prussian king depicts the ideal ruler.

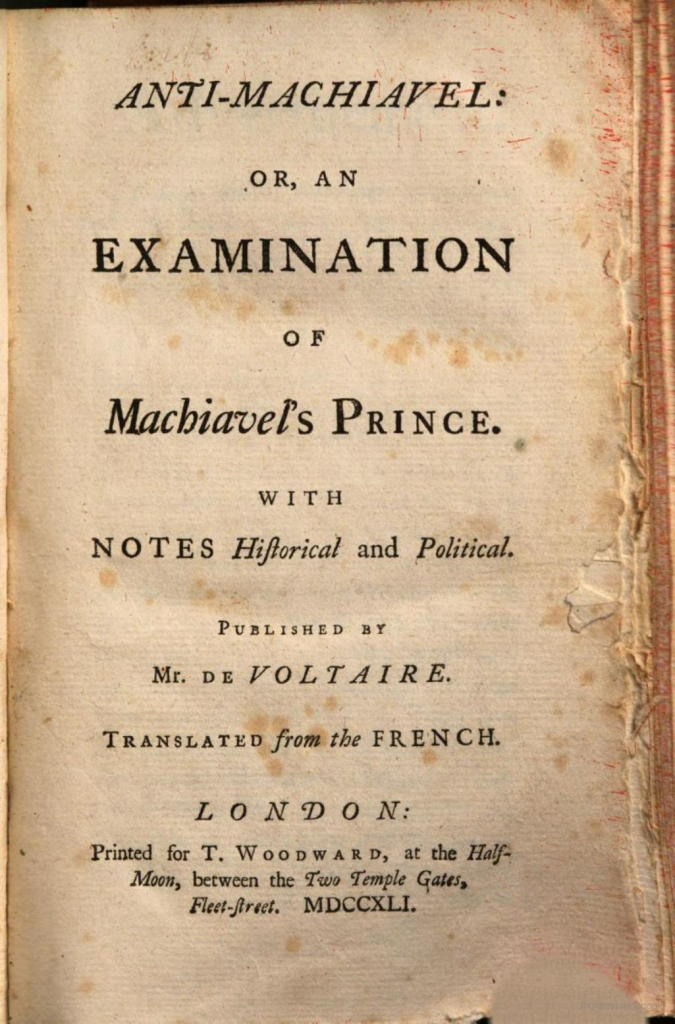

Anti-Machiavel

“Anti-Machiavel” is an 18th century political essay, one of the most famous works of enlightened absolutism. Written by the Prussian king, Frederick II, or Frederick the Great, it is an example of the political philosophy of 18th century. Said differently, it’s a reflection of 18th century political mindset that was new and modern, oriented towards the well-being of the nation, and not the political machinations of the rulers, as it was emphasized in “The Prince” by Niccolo Macchiavelli. The work was published in September 1740, a few weeks after Frederick became king.

18th Century Absolutism: A Matter of Trust

According to Frederick the Great, a good ruler of the 18th century is the one who respects the trust his people gave him:

Therefore, it’s clear Frederick the Great supported the idea of the ruler having all the power in his hands, but he serves his people, and not sacrifices them in his own schemes for acquiring more power.

18th century ruler: How to Govern Conquered Land?

There are three ways to govern conquered area, according to Frederick the Great: ruin it, reside there, and leave the citizens their freedom, making them pay a tribute “under the government of a few Persons who may keep the People in Obedience and Allegiance.”

Frederick also approves total destruction in some cases:

Clearly, Frederick the Great was intrigued by the ideas of control and power, but it must be noted, these ideas had to be in harmony with the idea of the new, 18th-century ruler.

Laws and Arms in 18th Century Absolutism

“There cannot be Good Laws where there are not Good Arms”, notes Frederick reflecting upon the successful 18th-century state. The army the ruler leads can be his own, mercenary, auxiliary, or a mixture. If the ruler confided only in mercenary or an auxiliary army, that wasn’t wise, because they weren’t strongly organized, they were ambitious and treacherous:

Therefore, to avoid the loss of power, Frederick II notes the ruler has to go to war in person and “take upon him the office of General.” So, an army was also an important part of the government. More precisely, for the 18th century ruler, it was a mean to acquire, strengthen and keep absolute power in his own hands.

Frederick II’s idea of successful government was in accord with the 18th century idea of enlightened absolutism. The ruler needed to have all the power. So, the “successful government” of the 18th century maybe can be described as absolute power in service for the citizens. The ruler was an enlightened absolutist, but his government was there for the well-being of the citizens he governed, not for his own personal schemes.

One thought on “‘Anti-Machiavel’: 18th Century Government – Absolute Power in the Citizens’ Service ”