Birger Jarl, 17th-century engraving by Erik Dahlberg

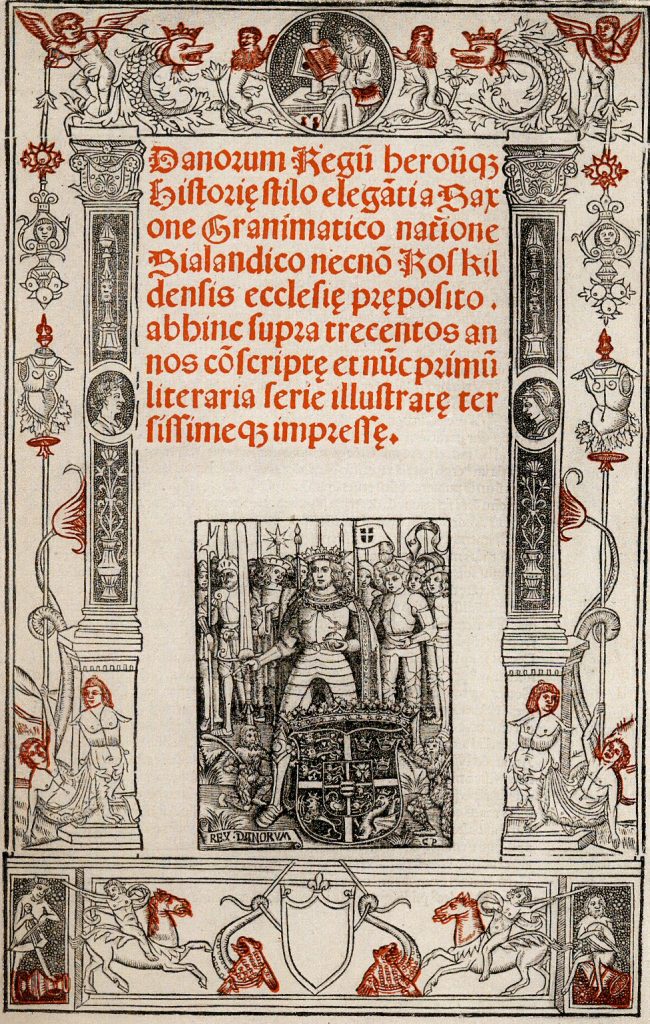

The twelfth-century Gesta Danorum (Deeds of the Danes) by Zealand scribe Saxo Grammaticus chronicles ancient hostilities between Vikings and Finnish tribes living between the Arctic and Baltic seas. However, the earliest relatively verifiable account of the Second Swedish Crusade against the Tavastians – a people who lived beyond the southwest Finns proper (Egentliga Finnar) region of Turku – appears in the anonymous fourteenth-century Erik Chronicle (Erikskrönikan).

It is generally accepted by historians that Birger Jarl (Magnusson) – the progenitor of the Ostrogothian House of Bjelbo – led the crusade in 1249 and became the most powerful man in Sweden after the death of King Erik XI in 1250. Birger’s rise to power and papal-supported military campaign culminating in his establishment of Stockholm soon after Erik’s death – would not have been possible without the Treaty of Lödöse between Norway and Sweden. In essence, the 1249 treaty effected before the Second Crusade allowed the Swedes to focus on their Baltic campaigns without overly concerning themselves with protecting their western territories. By making a lasting peace with Norway, the nascent Swedish state was free to focus on eastern expansion and developing commercial activity from their future capital.

Old Enemies and Northern Crusades

In the fifth book of the Gesta Saxo Grammaticus distinguishes between Finland (Finnimarchia) and Bjarmaland (Biarmia, a region presumably further north) by identifying their two kings and their conflicts with Norwegian and Swedish Vikings – particularly a mythological Swedish berserker named Arngrim, although Saxo goes on to explain that…

…the Finns are the people of the extreme north, and indeed the habitable part of the world is complex in culture and habitation. …No other nation enjoys a more rapid shooting skill. They fight with large and broad arrows. …Their habitation is uncertain, and their houses are wandering, and wherever they have taken possession of the wild, they rent their seats. Mounted with the beams… covered with snow, they traversed the ridges. Arngrimus, having conquered them, crushed them for the sake of glory.[1]

It is believed Swedes began colonizing the uninhabited coastal islands of southwest Finland during the twelfth-century crusades. Crusading in the Baltic intensified in the early thirteenth century under the initiatives of various Germanic military orders from the sea’s southern coast, and eventually extended their influence into present-day Estonia. The historian Pentti Aalto notes that the Swedish crusade carried out by Birger in 1249 was prompted by Pope Gregorius IX, who in 1237 “exhorted the Christians to crusade against the pagan Tavastian tribe… causing much harm and damage to the Roman Catholic Christians in Finland.”[2]

In order to carry out the papal-sanctioned project, however, Swedish leadership under Erik XI and Birger Jarl – who had as late as 1247 defeated their own contenders (the Folkung Party) at the Battle of Sparrsätra – needed to ensure their western territories were safe. Thus, peace with Norway’s King Haakon IV became prudent.

Treaty of Lödöse

Warring in the Norwegian and Swedish borderlands had been going on for generations, but a prolonged civil war in Norway and peace overtures by King Haakon IV beginning in the early 1240s offered an opportunity to the Swedes.

Rapprochement was difficult, and so when the two sides finally met in 1249 at the western border town of Lödöse, Birger consummated their agreement by offering his daughter Rikissa’s hand in marriage to Haakon’s son – heir to the Norwegian throne. According to the Icelandic Hákonar saga, written in the 1260s by historian Sturla Thórdarson:

King Hakon camped… to the west of the river, opposite Ljoðhus [Lödöse], and waited there for the earl [Birger] to come. But then men went between them, and there was spoken the good word of the young King Hakon, and many other things about their peace. …They firmly understood that peace should stand between Norway and Sweden; and whose enemies shall be… in other countries. And with the army King Hakon fastened the young lady Rikizu, daughter of the earl… And after this [they] parted with the greatest affection.[3]

Birger Jarl Conquers the Tavastians

With peace in western Sweden assured, Birger commenced the campaign against the Tavastians. Gustaf Edvard Klemming, chief librarian at the Stockholm Royal Library who printed the first version of the Erikskrönikan in 1865, believed the crusade took place in 1249-1250. Originally written in poetic verse, a literal translation of the Erik Chronicle, reads:

“With their banners they went inland as Christ guided their hands…Their shields they carried shined, over the land their helmets shown. They were gladly tempted to try their swords upon the Tavastian heathens… Christians built a castle there …called Tavesteborg…”[4]

During the crusade in Finland, King Erik passed away and Birger’s young son Valdemar was selected to be king. When Birger returned, he founded the city of Stockholm and ruled through his son. Finland thereafter became known as the Swedish “Easternlands” (Österlanden) and remained part of that realm for more than five centuries.

[1] Alfred Holder, ed., Saxonis Grammatici Gesta Danorvm (Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner, 1886), 165.

[2] Pentti Aalto, “Swells of the Mongol-Storm Around the Baltic,” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 36, no. 1/3 (1982), 11. “In 1256 the Swedes, Finns (including the Tavastians), and the Scandinavians from Livonia carried out an expedition at the mouth of the Neva, but were again defeated by Alexander who then in the following winter attacked the Tavastians across the ice of the Gulf of Finland.” (13) See: Richard Spence, “Pope Gregory IX and the Crusade on the Baltic,” The Catholic Historical Review 69, no. 1 (1983): 1–19.

[3] Sturla Þórðarson (Gudbrand Vigfusson, ed.), Icelandic Sagas (Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar)[The Saga of Haakon Haakonarson], vol. 2 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1887), 263-4.

[4] Gustaf Edvard Klemming, Gamla eller Eriks-krönikan. Folkungarnes brödrastrider med en kort öfversigt af närmast föregående tid. 1229-1319. [Old or Erik’s Chronicle. The People’s Kings’ fraternal conflicts, with a brief overview of the immediately preceding period. 1229-1319.] (Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt & Sönner, 1865), 5-6. For an English version truer to the rhyming nature of the Chronicle see Erik Carlquist,Peter C. Hogg, Eva Österberg, The Chronicle of Duke Erik: A Verse Epic from Medieval Sweden (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2011), 36-37.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.