The marketplace in Novgorod, circa 15th century, by Apollinary Vasnetsov

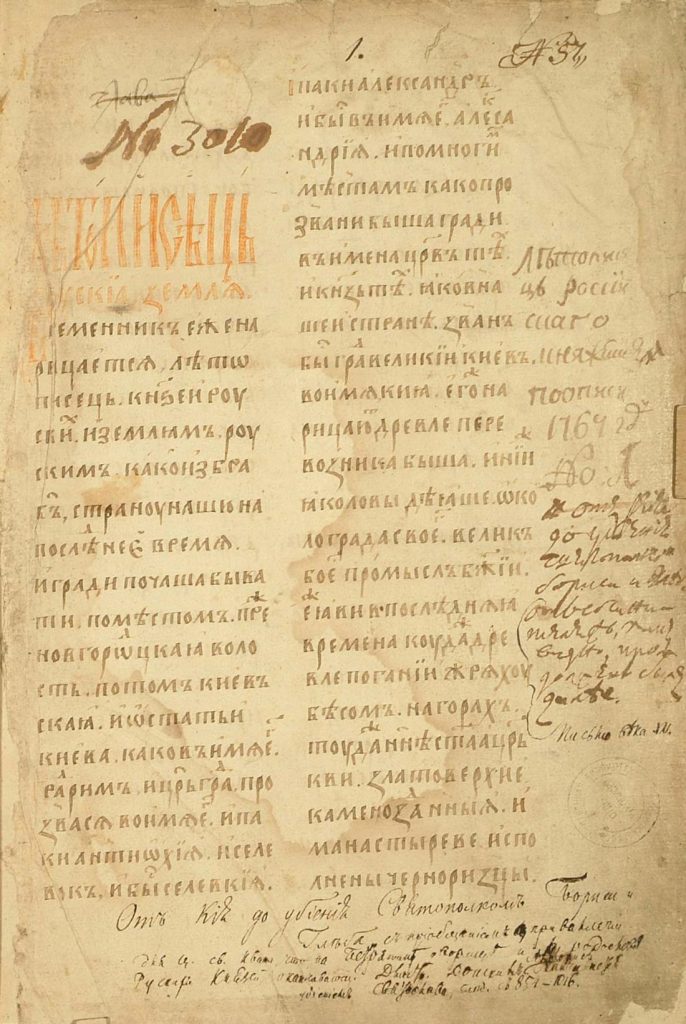

Established as a republic in 1136, much of the history of Novgorod was written in the Old Russian Chronicle of Novgorod. Also known as The Novgorod First Chronicle, the document praising four centuries of conflict and achievement of the capital connecting the Baltic and Byzantine worlds begins in 1016 and ends in 1471 after Novgorod finally succumbed to Moscovite rule. A theme of the Chronicle documenting Novgorodian expansion from the Dnieper to the Polar Urals lies in the expression “beyond the Volok” – which roughly meant “beyond the portages” – or the regions north and east of its lucrative fur and mineral trade.

Although the Novgorodians were the dominate pioneers and traders in the White Sea during the medieval period they were not the exclusive explorers. Norwegian Vikings called the area around Archangel “Bjarmaland,” and the Norse sagas attest to their activity there in the late 800s and early 900s. The most well-known Norse expedition was led in 1026 by Thorir Hund (“Thorir the Hound”) – a chief of Halogaland in northern Norway around modern-day Tromsø. According to the Heimskringla – a history of the Norwegian kings written in Old Norse sometime in the 1230s by Icelandic historian and parliamentarian Snorri Sturluson, the expedition started out benignly enough, but the Norsemen ultimately decided to take what they could not obtain through trade:

When they came to Biarmaland they went straight to the merchant town and the market began. All who had money to pay with got filled up with goods. Thorer also got a number of furs, and of beaver and sable skins. Karle had a considerable sum of money with him, with which he purchased skins and furs. When the fair was at an end they went out of the Vina [Dvina] river, and then the truce with the country people was also at an end. When they came out of the river they held a seaman’s council, and Thorer asked the crews if they would like to go on the land and get booty.[1]

Baltic Foes and Mongols

In the early 1200s the Swedes reappeared to threaten Novgorod’s position but were neutralized after Novgorodian forces led by Prince Alexander Nevsky decisively defeated them “by the power of St. Sophia” at the Battle of Neva on July 15, 1240. More important to their victory, however, may have been the fact that the Karelians – who occasionally warred with Novgorod – sided with the Novgorodians against their common enemy. Two years later, Alexander sealed his legacy by repelling the Teutonic Livonian Order in a battle held on a frozen lake separating modern-day Russia and Estonia.[2]

To the south and east, the Mongolian invasion of Kievan Rus’ lands began in 1223 with their victory at the Kalka River and culminated with the siege and destruction of Kiev in 1240. Novgorod was the singular Rus principality to avoid this onslaught and thus became the western Orthodox vanguard abutting the khanates – the rulers that replaced the Golden Horde after the Mongols. At the time Moscow had been a mere fort connecting Volga River commerce, but it too was destroyed and subjugated by the Mongols.[3] The mid-twentieth century historian George V. Lantzeff noted that the Suzdal princes who ruled over Moscovy during this period “were crushed” by the Mongol invasion and “their imperialistic plans for the domination of the Volga and its Asiatic trade were frustrated; their attempts to exploit the Novgorodian colonies and to control Novgorod itself came to an end.”[4]

As Lantzeff described, the lack of rivals between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries marked Novgorod’s golden age. Adding to that, in 1323 ambassadors sent by Sweden’s King Magnus formalized “an everlasting peace” with Novgorod and consummated that agreement by allowing the erection of a Novgorodian fortress “at the mouth of the Neva on Orekhov island” on Lake Ladoga. With their rear secure, the following year Novgorodian forces were once again “beyond the Volok” seizing the town (Veliky) Ustyug – an important location upriver on the Northern Dvina at the confluence of the Sukhona and Yug rivers. Ustyug appears in the Chronicle frequently as it became a flashpoint in the rivalry between Novgorod and an ascendant Moscow.[5]

Return of the Scandinavians and Rise of the Moscovite Tsars

In the late 1300s contenders began to seriously jeopardize Novgorod’s hold over its Trans-Volok frontier. In 1398 Novgorod recovered “outlying” Ustyug and the Northern Dvina from Moscow but thirteen years later, the return of the Svei (Swedes) from the west and the Norwegians (“Murman people”) from the north meant that Novgorod was on the defensive. In response, the governor of Dvina was ordered by Novgorod to defend against the Norwegian marauders while an attack was launched “from beyond the Volok to make war against the Murman people, and ravaged their country.” The effect of the assault against the Norwegians was limited because in 1419 some five hundred of them returned, burned three churches, and sacked the Michael Monastery in Archangel.[6]

Writing in the early twentieth century Sir Charles Raymond Beazley used 1445 as the final year Novgorod tried to reestablish its dominance of the region east of the Trans-Volok, but their initial success gave way to “ruinous defeat.” After that, it was only a matter of time before Ivan III, the “‘Re-uniter of Russian lands’” arrived in 1471 to strike the final blow at the Battle of Shelon. Coincidentally, Beazley’s fascinating with the limits of Novgorodian influence in the Northern Dvina and on the White Sea occurred only a few short years before the Allies used that same outlet to supply the forces opposing the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. The North Russia Intervention, begun in the spring of 1918 after the October Revolution, ultimately failed – just as Novgorod succumbed to the rise of Moscow “beyond the Volok.”[7]

[1] Samuel Laing, The Heimskringla or the Sagas of the Norse Kings from the Icelandic of Snorre Sturlason, Vol. 3(New York: Scribner & Welford, 1889), 92.

[2] Robert Michell, Sir Charles Raymond Beazley, et al, The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471, (London: Offices of the Society, 1914), 84-86. See: Artis Aboltins and Erich Anderson, “Controversial Hero: The Reign of Alexander Nevsky.” Medieval Warfare 4, no. 1 (2014): 6–10.

[3] See: Konstantin Nossov, “The Ravage of Rus’: The Mongols’ Western Campaign.” Medieval Warfare 5, no. 6 (2016): 35–41.

[4] George V. Lantzeff, “Russian Eastward Expansion before the Mongol Invasion.” American Slavic and East European Review 6, no. 3/4 (1947), 10. See also: David B. Miller “The Many Frontiers of the Pre-Mongol Rus’.” Russian History 19, no. 1/4 (1992): 231–60.

[5] The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471, 122-123. Relative peace between Sweden and Novgorod lasted about twenty-five years. In 1348, Magnus organized a crusade against Novgorod on the Neva.

[6] Ibid. 170-171, 181, 189.

[7] Sir Charles Raymond Beazley, “The Russian Expansion Towards Asia and the Arctic in the Middle Ages (to 1500).” The American Historical Review 13, no. 4 (1908), 734.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

3 thoughts on ““Beyond the Volok”: The Medieval Frontier and Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471 (Part Two)”