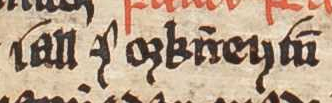

Rollo, Duke of Normandy. Detail from the roll of the dukes of Normandy, 13th century

According to the thirteenth-century Icelandic Heimskringla, before the Viking Rollo became the first ruler of Normandy and of the Normans – the people who later conquered much of England, Ireland, and Sicily – he was known as Hrolf Ganger, or Rolf the Walker. Why the son of Earl Rognvald (Eysteinsson) – the legendary Norwegian nobleman and friend of King Harald Fairhair – ended up creating a powerful ducal dynasty in the early tenth century on the coast of modern-day France is less known because it may have involved his older brother Einar – who at the behest of their father sailed to the Orkneys from their home in Møre (western Norway) and established his own dynastic earldom enduring centuries.

The saga describes Rognvald as having six sons: two by his wife Hild, “Rolf and Thorer” and Ivar by another marriage (possibly Ragnhild). Before that, “Ragnvald had also three sons by concubines, – the one called Hallad, the second Einar, the third Hrollaug; and all three were grown men when their brothers born in marriage were still children.” When the storm of fury, fate, and fortune finished its course; Rognvald was dead by the hands of King Harald’s wicked sons, Harald’s son Halfdan was executed by Einar in revenge on the island of North Ronaldsay, and Rolf was banished from Norway and sailed to the Orkneys before conquering the coast of France.[1]

Inheriting the Orkneys

According to the Heimskringla, after becoming the first true king of Norway at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872 Harald Fairhair, the “dearest friend” of Rognvald, sailed west to the Scottish Isles to war on the Vikings who during the summer “plundered far and wide in the middle part of Norway” but lived in the Hebrides, Orkneys, and Shetlands during the winter. Rognvald’s son Ivar accompanied Harald during his campaign and was killed in battle. As a result, “King Harald gave Ragnvald, as a compensation for the loss, the Orkney and Shetland isles… but Ragnvald immediately gave both these countries to his brother Sigurd, who remained behind them…”[2]

“jarl í Orkneyum”, Codex Flateyensis, folio 101v, 14th century

This occurred in the late 800s. The twelfth-century Saga of King Olaf Tryggvason written by the Icelandic monk Oddr Snorrason (which likely informed the Heimskringla) adds that when Sigurd suddenly died Rognvald “sent into the west his son Hallad, upon whom King Harold bestowed the title of Earl.” The problem for Rognvald, however, was that Hallad soon “grew tired of living there” and “formally rejected the position of Earl,” and returned home to Norway to live as a farmer. Rognvald “was much displeased” with Hallad and held a meeting with his sons. That Oddr Snorrason chronicled two separate but similar accounts of the meeting indicated its importance. While the first account is mostly about Einar, the second account is about Rolf and his legacy:

“My sons,” he said, “are not like my forefathers.” To this remark of his father, Einar answered: “You give me little of your affection; it will be a very small matter to me to lose such regard as I have received from my childhood until now… If, therefore, you will grant me some assistance, I will go to the Orkneys, and I promise you that I will never come back to Norway.” “I shall be well pleased,” the Earl answered, “if you come not again; but I have little hope that you will ever be an honour to your kinsmen… The Earl then gave Einar a ship of war, sufficiently well manned, and in the autumn he sailed to… the Orkneys, [and] he made war upon the Wickings who had settled there, and slew them. He then became Earl over the Islands, and was a great and powerful chief.

Rognwald then called his sons together and asked which of them would accept the Earldom of the Orkneys. Thori[r] answered that he would leave the decision to his father, whether he should go into the west or not.” You answer well,” said the Earl; “but you are a legitimate son, well fitted to be a chief, and you must hold rule here, and inherit after me.” Then Rolf came forward and offered himself. “You are well fitted both in strength and acquirements,” replied the Earl; “but I think there is an overbearing temper and a warlike ambition in you, too great to let you thus settle quietly down to rule so small a kingdom.” …The Earl then sent his son Einar to the Orkneys.[3]

Rognvald’s Death and Einar’s Revenge

The Saga of King Olaf Tryggvason also describes Rognvald’s murder by Harald’s two sons, Halfdan and Gudrod, who “became excessively overbearing in their conduct, slaying the King’s Earls and other powerful men.” One spring they sailed to Møre, surprised the earl at his home, and burned it down with dozens of other people inside.

To his father’s disgust “Gudrod took to himself the authority exercised by the Earl; but shortly afterwards he placed himself in his father’s hands, and was reconciled to him.” As recompense “King Harold granted to Earl Rognwald’s son Thori[r] all his father’s inheritance, as well as the title of Earl, and gave him his daughter Olof Arbot to wife.” Meanwhile, immediately after Rognvald’s death, Halfdan sailed to the Orkneys and usurped Einar’s position as ruler before Einar and his men caught him in the autumn on an island and gruesomely executed him. When Harald heard of Halfdan’s death, he “sailed west with an army to the Orkneys,” but rather than fight, Einar fled and brokered a financial “reconciliation” payment of sixty pieces of gold. In the end, “Einar ruled over the Orkneys for a long time, and died a natural death, leaving three sons, Arnkel, Erlend, and Thorfinn Skullcleaver.”[4]

Banishment of Rolf

The Heimskringla says that sometime later Rolf had a falling out with Harald after plundering in the Baltic and slaughtering cattle on the “coast of Viken,” which was within Harald’s realm and considered an affront to his authority. News of the event put Harald “in a great rage; for he had forbid, by the greatest punishment, the plundering within the bounds of the country.” Harald “assembled a Thing, and had Rolf declared an outlaw over all Norway.” Rolf’s mother Hild attempted to assuage Harald on behalf of Rolf “but the king was so enraged that her entreaty was of no avail.” The saga then states that Rolf “went afterwards over sea to the West to the Hebrides, or Sudreys; and at last farther west to Valland [western France], where he plundered and subdued for himself a great earldom, which he peopled with Northmen, from which that land is called Normandy.”[5]

Did Rolf enlist Einar or perhaps his sons to help him invade Normandy? There is no historical evidence he did, but it is certainly plausible considering their life circumstances and overlapping reigns. The Heimskringla states that at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872 – the same period Vikings intensified raiding in Normandy and Brittany – there were foreign soldiers “From the West countries… English and Scotch, [and] swordsmen from the far French coast.”[6] In his 1982 work, Normandy Before 1066, David Bates, the foremost authority on the history of the Normans, wrote that “Rollo himself was closely related to the Norwegian rulers of the Orkneys. ‘Normandy’ received settlers who had dwelt on other territories: the existence of place-names containing an Anglo-Saxon element in the Pays de Caux suggests the immigration of Scandinavians who had lived for a considerable time in England.”

Four years later, Neil Price cited a number of scholars (including Bates) to assert “place-name research suggests settlers from Scandinavia, England, Ireland and possibly Orkney.”[7] The Cotentin peninsula, in northern Normandy, was settled by Viking immigrants whose geographical origins would have been difficult to distinguish.[8] The connecting remains a mystery, but during an era when people moved from overpopulated areas in search of new places to settle, it is possible the more ambitious warriors in Einar’s island kingdom greeted Rolf’s campaign as an opportunity for themselves and their future progeny.

[1] Samuel Laing, The Heimskringla or the Sagas of the Norse Kings From the Icelandic of Snorre Sturlason, vol. 1 (New York: Scribner & Welford, 1889), 369-370. Rolf received the nickname “the Walker” because he “was of so stout a growth that no horse could carry him, and wheresoever he went he must go on foot…” (370); The hereditary line of the “Earls of Orkney… of Ragnvald Earl of More… appears to have been broken in upon in 1129…” (Laing, intro. 156)

[2] Ibid. 368-370.

[3] John Sephton, ed., Oddr Snorasson, The Saga of King Olaf Tryggwason, who reigned over Norway A. D. 995 to A. D. 1000 (London: David Nutt, 1895), 130-132, 337. “Wickings” were the Vikings who raided Norway in the summer. The twelfth-century Orkneyinga saga (which likely informed Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla) states that Einar “was stubborn and taciturn, disagreeable and avaricious, yet a great warrior.” He was also “called Torf-Einar because he cut peat for fuel.” See: Joseph Anderson, ed. The Orkneyinga saga (Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1873), 1-4.

[4] Ibid. 132-133. The Heimskringla depicts Halfdan’s death: “Earl Einar went up to Halfdan, and cut a spread eagle upon his back, by striking his sword through his back into his belly, dividing his ribs from the back-bone down to his loins, and tearing out his lungs…” (Laing, vol. 1, 379)

[5] Laing, The Heimskringla, vol. 1, 371-2. Laing writes: “Valland was the name applied to all the west coast of France, but more particularly to Bretagne, as being inhabited by the Valer or inhabitants of Wales and Cornwales (Cornwall), expelled by the Saxons from Great Britain in the last half of the fifth century. The adjective Valskr (Welsh) was used to denote what belonged to this Valland. …Gange-Rolf was baptized in 912, and died in 931. He probably left Norway about the year 890.” (372)

[6] Ibid., 364.

[7] David Bates, Normandy Before 1066 (New York: Longman, 1982), 7; Neil S. Price, “The Vikings of Brittany,” Saga-Book 22 (1986), 39/357. “[S]ee Fellows-Jensen 1988, Davis 1976, 21-5; Bates 1982, 16-19; Adigard des Gautries’ definitive studies 1951-9 and Guinet 1980; the Celtic names point more closely to the Hebrides…”

[8] See: Élizabeth Ridel, “From Scotland to Normandy: The celtic sea route of the Vikings,” In West over Sea (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 81. “[T]he Vikings also followed another sea route to the coast of France, one which was less direct and, because of this, certainly less used. This route belonged to the Norwegians who, from their settlements in Scotland and Ireland, sailed either directly to Brittany or Aquitaine, or indirectly… to the Channel Islands and the coast of The Cotentin (Normandy).”

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

One thought on “Earl Rognvald’s Sons: Einar of the Orkneys and Rolf, Conqueror of Normandy”