Cenotaph of the Alamo defenders (fragment), San Antonio, Texas, USA (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In 1923 Charles Scribner’s Sons, the famous New York-based publishing company founded in 1846 by Charles Scribner at the start of the Mexican-American War, released The Autobiography of Davy Crockett (1786-1836) – a work about the famous Tennessee frontiersman-turned politician who died in Texas at the Battle of the Alamo.

Even before the storming of the Alamo by Mexican forces, Crockett was well known and thus his early death punctuated a life that achieved legendary status – making him into an American icon and storybook favorite in an age of heroics. In the accompanying bibliographical note following the introduction written by poet and novelist Hamlin Garland, there is an explanation regarding the works about Crockett published before his death:

The Sketches and Eccentricities of Col. David Crockett, of West Tennessee (1833), as an unauthorized work which its subject resented, has properly no place here; but A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett, of the State of Tennessee (1834) is now once more given precisely as it first appeared, with a very few obvious misprints corrected, as is An Account of Col. Crockett’s Tour to the North and Down East (1835), with the verbose and repetitious political speeches all omitted except one and the scattered arguments and reflections at the end entirely omitted.[1]

Pseudo-Crockett

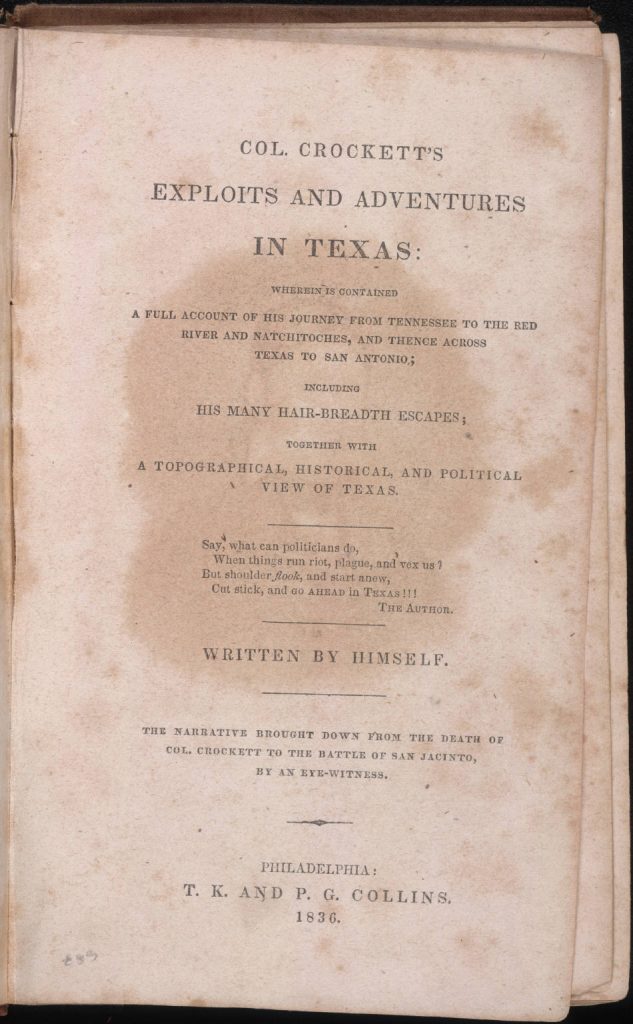

Crockett’s persona sold books, and as Garland noted, most of the 1923 “autobiography” – up until the point Crockett went to Texas to meet his destiny – was the 1834 autobiography A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett. The Remaining one-third of the story centering around Texas was the 1836 book, Col. Crockett’s Exploits and Adventures in Texas.

Garland was not shy in pointing out that the 1836 work was “spurious no one now seriously doubts: even if the Colonel had been willing or able to write any such journal as he is credited with — as he almost certainly was not — he would not have made it a cento of extracts from other frontier materials of the time — as his pretended editors did.” Garland further explained the fake autobiography:

In the original form the Exploits and Adventures has a preface signed by Alex. J. Dumas, who, writing from New Orleans, says he had the manuscript from Charles T. Beale; and a final chapter recounting the last hours of Crockett after he broke off his journal. It has seemed worth while to reprint this pseudo-Crockett, except for the preface and the final chapter, not only because it is itself interesting but because the existence of such a book shows that there was current at the time a popular legend and literature of the frontier which made it possible for catchpenny hacks to manufacture a reasonably characteristic, reasonably convincing “autobiography” of a dead hero while his death was still in the news.[2]

The Legend Lives On

Indeed, Exploits and Adventures was most likely the imaginative work a one or two men anxious to make money off the popularity of the American legend and his well-known sense of humor, which undoubtedly inspired authors like Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), who was born one year before Crockett’s death. Exploits and Adventures noted how Crockett’s 1835 election loss contributed to his decision to go to Texas but in the verifiable 1834 Narrative of the Life of David Crockett – the autobiography actually written by Crockett – there is not one reference to “Texas.”

Although Crockett discussed Texas in speeches and letters, the absence of commentary is somewhat enigmatic given it defined his legacy and leads one to believe he did not deeply ponder the Lone Star Republic until destiny brought the two together. In the preface of his 1834 Narrative Crockett harangued James Strange French, author of the 1833 work, The Sketches and Eccentricities of Col. David Crockett, of West Tennessee: “A publication has been made to the world, which has done me much injustice; and the catchpenny errors which it contains, have been already too long sanctioned by my silence.” Crockett despised French’s work, not because it tarnished his good name, but because it was narrated in a manner that led the reader to believe it was written by Crockett himself:

I don’t know the author of the book — and indeed I don’t want to know him; for after he has taken such a liberty with my name, and made such an effort to hold me up to public ridicule, he cannot calculate on any thing but my displeasure. If he had been content to have written his opinions about me, however contemptuous they might have been, I should have had less reason to complain. But when he professes to give my narrative (as he often does) in my own language, and then puts into my mouth such language as would disgrace… he must himself be sensible of the injustice he has done me, and the trick he has played off on the publick.[3]

The fact that Crockett was famous before his battlefield death in the opening siege that presaged the U.S. war with Mexico ultimately says more about American fascination with the frontier and the myths that arose from creative writers looking to capitalize off an icon who represented an epic chapter in western history. Crockett did not know Texas would be his defining moment or he would otherwise have mentioned it in his memoirs.

He thought he would live to write another chapter of that story, but the irony is that his name and the myths associated with it were etched in a timeless manner because of the adventurous and risky way he lived. Two years before his death, he wrote: “There must therefore be something in me, or about me, that attracts attention, which is even mysterious to myself. I can’t understand it, and I therefore put all the facts down, leaving the reader free to take his choice of them.”[4] Facts or no facts, Crockett’s legend lives on.

[1] Davy Crockett, The Autobiography of Davy Crockett (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1923), 11

[2] Ibid. See: Alex. J. Dumas, ed., Col. Crockett’s exploits and adventures in Texas, written by himself (London: R Kennett, 1837).

[3] Davy Crockett, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett, of the State of Tennessee, Written by Himself (Philadelphia: E.L. Carey and A. Hart, 1834), 3-4. See: James S. French, Sketches and eccentricities of Col. David Crockett of west Tennessee (New York: J.J. Harper, 1833).

[4] Ibid. 7

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.