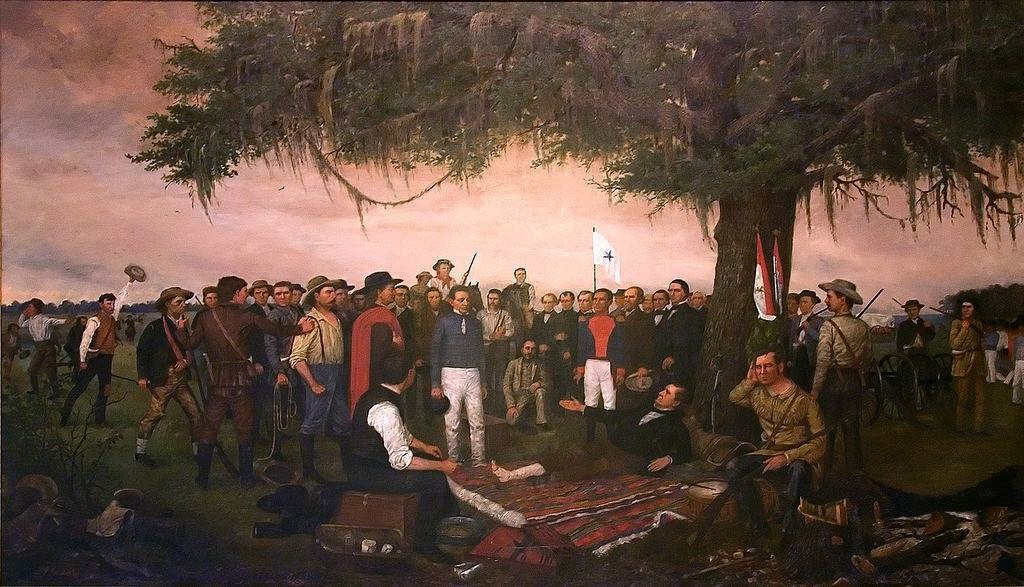

General Antonio López de Santa Anna in a Mexican military uniform, mid-19th century

The Texas Revolution beginning in the fall of 1835 achieved its goal of independence after defeating General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto April 21, 1836. Fought on the heels of the martyred heroes at the renowned siege of Alamo lasting from February 23 to March 6, the victory of the small Texan force against a larger Mexican Army was sweetened when Santa Anna was captured the following day while fleeing in a private’s uniform. On May 14, Santa Anna signed the Treaty of Velasco granting Texas independence – an agreement Mexican officials forever contested due to claims the Mexican president was under extreme duress and threat of execution. News of the victory was not only celebrated in Texas, but in the United States – as that country contributed men and munitions to aid the insurrection. The historian Eugene Barker noted that when the war began…

Public meetings were held in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Baltimore and Washington. Large sums of money were subscribed, and from New York, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati companies of volunteers were sent. Throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana the excitement was high and many volunteers “emigrated” to Texas, the expenses of their equipment being paid by those who remained at home.[1]

Friends and Generals

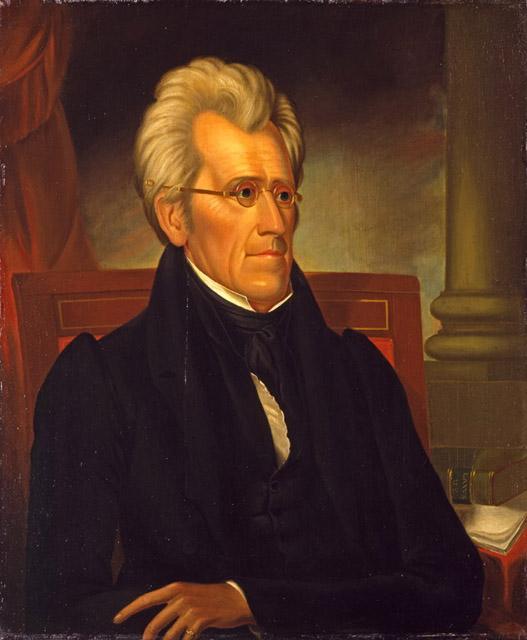

Although it was rumored President Andrew Jackson conspired with the first president of the Republic of Texas General Sam Houston to foment the rebellion with the ultimate goal of peeling away Mexico’s northern department into the hands of Americans, such speculation was unfounded.[2] Houston was not coy about his “desire is that our country Texas shall be annexed, to the United States” because he made his intentions known soon after the battle.

For his part, Jackson made every effort to have Texas recognized as an independent country at an early period. The two were good friends, and it was agreed upon by all parties – including Santa Anna – that a visit to Washington D.C. by the defeated caudillo – escorted by agents of the Texas government – would ameliorate a tense situation and “consummate his pledges given” when he signed the treaty. Houston wrote Jackson:

Dear Sir, Allow me the pleasure of introducing to the notice, and kind attention of your Excellency, General Antonio Lopez de Sant Anna, the President of the Republic of Mexico. The distinction, and character of Genl Sant Anna, will supersede the necessity of my saying anything in his favor, so far as his reputation is a portion of the history of mankind! As an individual, I claim leave to recommend him to your manly, and generous regard. Not unaware, that ma[n]y circumstances connected, with the prejudices of the present time, may be calculated to influence, most minds; and create a feeling which if indulged might be injurious, to the reception, which I claim to solicit for Genl Sant Anna in Washington; I feel confident, that with you, he can at all times realize, a just estimation, of his worth, as a soldier and a Gentleman. As such, I hope you will allow me to recommend him to your attention, and regard. Your Friend[3]

On December 22, 1836, the Richmond Enquirer wrote that the “visit of Santa Anna to Washington is shrouded in some mystery.” Indeed, it was unknown exactly what the two generals discussed: “Gen. Jackson proposed to become a mediator between the two governments,” the article read without citing specifics. There was surprisingly little reporting on the visit. Other rumors of European recognition of Texas existed and renewed war and “invasion” of Texas from Mexico, but there is no evidence of their conversations for historians to cite, nor did either general leave any comments behind for posterity. John Spencer Bassett noted in his 1911 work, The Life of Andrew Jackson, that Santa Anna arrived in Washington in early 1837 and was “well received and set out for his home in February, promising to use his efforts for peace.” Predictably Santa Anna could not keep that promise – if it was truly made at all. However, if Bassett’s timeline is correct, Santa Anna was in Washington for a considerable amount of time.[4]

[1] Eugene C. Barker, “President Jackson and the Texas Revolution,” The American Historical Review 12, no. 4 (July, 1907), 804, 797.

[2] Ibid. 809. “Throughout his administration General Jackson displayed, it seems to the writer, a desire to maintain unsullied the dignity and honor of the United States in regard to the Texas question. …but he did not connive at Houston’s revolutionary scheme, whatever it may have been… and he opposed precipitate recognition of the new state when the revolution was accomplished. (809)

[3] Amelia W. Williams and Eugene C. Barker, ed., The Writings of Sam Houston, 1821-1847, vol. 1 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1938), 487. Nov. 20, 1836.

[4] “Affairs of Texas” Richmond Enquirer, Dec. 22, 1836; John Spencer Bassett, The Life of Andrew Jackson (Garden City, NY: Double Day, Page & Company, 1911), 682.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.

2 thoughts on “The White House “Mystery” Meeting: Santa Anna meets Andrew Jackson, 1836-1837”