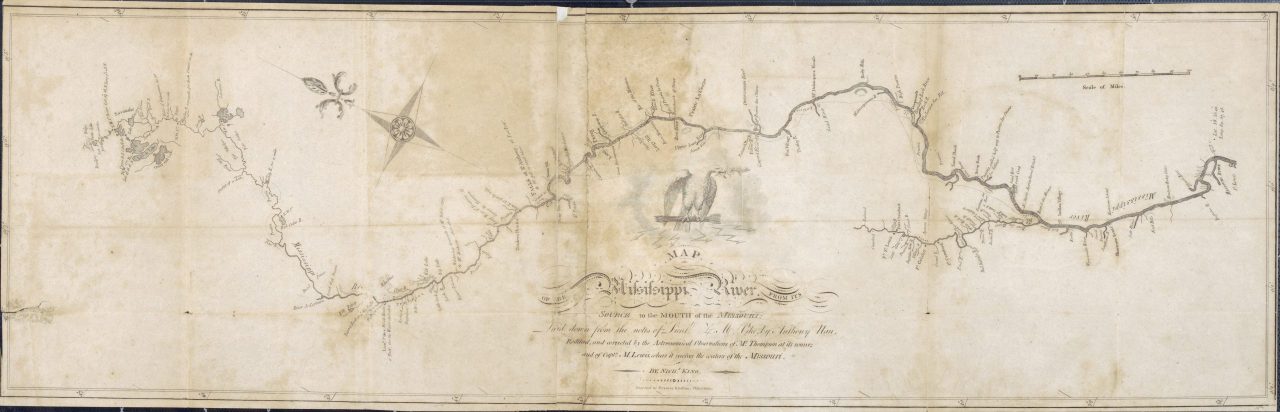

Map of the Mississippi River by Nicholas King, Zebulon Pike, Anthony Nau, and Francis Shallus, 1810

In 1803, with the approval of President Thomas Jefferson, American diplomat Robert R. Livingston purchased the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in a deal that nearly doubled the size of the United States. Two years later, the infamous U.S. general and first governor of Louisiana Territory, James Wilkinson – who was later accused of working with the Spanish to enrich himself – sent explorer Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike (1779-1813) up the Mississippi River to discover the source of that vital waterway, which was believed to be located somewhere within the Minnesota region.

Pike would go on to explore swaths of North America – becoming a legend in a growing nation. Not yet thirty years of age, other assignments for Pike on his journey north – which coincided with the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-6) into the west and Pacific – included expelling British fur traders operating in Minnesota, establishing contact with Indian tribes, and mapping the region. Pike set out in canoes with twenty men in late summer of 1805. In an 1872 publication of his expedition diary, he outlined his duties:

In the execution of this voyage I had no gentleman to aid me, and I literally performed the duties of astronomer, surveyor, commanding officer, clerk, spy, guide and hunter frequently preceding the party for miles, in order to reconnoitre, and returning in the evening, hungry and fatigued, to sit down in the open air, by firelight, to copy the notes, and plot the courses of the day.[1]

Fort Snelling Treaty

On September 21, the Pike expedition encountered the encampment of Jean-Baptiste Faribault, a fur trader from Lower Canada, in a place called St. Peters (Mendota Heights), near the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. Faribault, who died in 1860 at the age of 77, was said to be “the oldest white resident of what is now Minnesota.”

It was there, in the vicinity of an island known today as Pike’s Island, the explorer reached an agreement with tribal chiefs of the Sioux Nation to acquire territory to build a fort:

That the Sioux Nation grant unto the United States, for the purpose of establishment of military posts, nine miles square, at the mouth of the St. Croix, also from below the confluence of the Mississippi and St. Peters, up the Mississippi, to include the Falls of St. Anthony, extending nine miles on each side of the river, that the Sioux Nation grants to the United States the full sovereignty and power over said district forever.[2]

“Benumbed with cold”

One morning in late October, after embarking near present-day Little Falls, Pike and his men “became so benumbed with cold that our limbs were perfectly useless. We put to shore on the opposite side of the river, about two-thirds of the way up the rapids.” After building a fire, they realized that their “boats were nearly half full of water; both having sprung large leaks so as to oblige me to keep three hands bailing.” In addition, several of the men were sick, and so it was decided to make camp to rest and refit the boats:

My sergeant (Kennerman) one of the stoutest men I ever knew, broke a blood-vessel and vomited nearly two quarts of blood. One of my corporals (Bradley) also evacuated nearly a pint of blood, when he attempted to void his urine. These unhappy circumstances, in addition to the inability of four other men whom we were obliged to leave on shore; convinced me, that if I had no regard for my own health and constitution, I should have some for those poor fellows, who were killing themselves to obey my orders.[3]

Headwaters at Lake Itasca

In December, Pike set out again with twelve men (leaving the rest behind), killing deer to eat, using sleds like the local Chippewa Indians he encountered, and even “observed the flag of Great Britain flying” near Cedar Lake. However, a Chippewa Indian told them the flag was not flown by the British. “I felt indignant and cannot say what my feelings would have excited me to,” Pike wrote, “had he not informed me, that it belonged to the Indians.” By mid-January the expedition neared another fort near Big Sandy Lake:

On our march, [we] met an Indian coming into the fort; his countenance expressed no little astonishment, when told who I was and from whence I came; for the people in this country themselves acknowledge, that the savages hold in greater veneration, the Americans, than any other white people. They say of us, when alluding to warlike achievements, that “we are neither Frenchmen nor Englishmen, but white Indians.”[4]

In mid-February, after determining the source of the Mississippi River near Leech Lake, Pike’s expedition began their return – arriving at Pike Island in April. Writing in 1949, historian W.E. Hollon noted that “Pike knew of Lake Itasca’s existence, but he believed that Leech Lake was the more important of the two bodies of water.” Hollon also stated that, “Doubt of his ability was not like the man, and if it had been, he would never have reached his objective, in the face of innumerable hardships.”[5]

Legacy

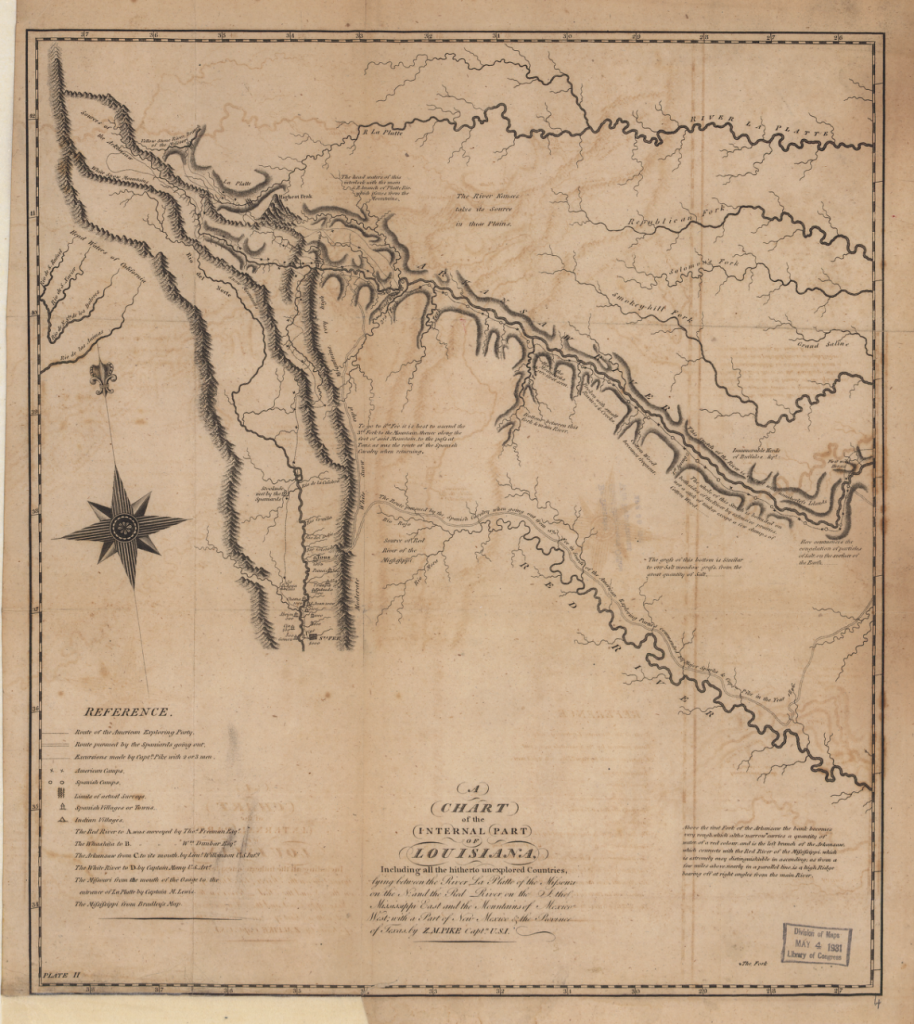

Pike’s second expedition for Wilkinson, who became a mentor of sorts for the explorer, was tasked with finding the headwaters of the Arkansas River originating in the state of Colorado. In 1807, as the group explored the Red River area of New Mexico (outside of American territory) they were captured by Spanish authorities and taken to Santa Fe. Soon after, they were released back into Colorado. During the War of 1812, Pike fought on the frontier against Native Americans allied with Great Britain, and was present at the Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana in late 1811. He rose in rank to become a general, and was killed during the American engagement at the Battle of York, in Toronto, April 27, 1813.

On September 27, 1919, five miles south of Little Falls along the Mississippi River, a ceremony was conducted dedicating a monument to Pike’s stay there in the winter of 1805-6. Honored with unveiling the modest monument on the ruins of the blockhouse built by the expedition, and sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution, was Lyman Warren Ayer, said to be “the first white child born in Minnesota” in 1834. The son of a missionary to the Chippewa Indians, Lyman was “mustered into service at Ft. Snelling” during the Civil War and survived to spend his life on the Minnesota frontier as a timber cruiser – often dogsledding the wintry region and making surveys before working with James J. Hill’s Northen Pacific Railroad in a similar capacity. The man with “remarkable vitality at his advanced age” who thought “nothing of walking forty or fifty miles in a day,” pointed out during the ceremony in Little Falls “how Pike and his party must have endured many hardships…”[6] Ayer would have known.

[1] Zebulon Pike, Pike’s explorations in Minnesota, 1805-6, Minnesota Historical Collections (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1872), 368.

[2] Ibid. 377-382. Pike’s diary indicates the treaty was made Sept. 23, 1805.

[3] Ibid. 388.

[4] Ibid. 396-8.

[5] W.E. Hollon, “Zebulon Montgomery Pike’s Mississippi Voyage, 1805-1806,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 32, no. 4 (1949): 450, 445–55.

[6] “Dedicate Monument” Little Falls Herald, Oct. 3, 1919; Clara K. Fuller, History of Morrison and Todd counties, Minnesota, their people, Industries and Institutions (Indiana: B.F. Bowen & Co.), 662-3.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.