Napoleon Crossing the Alps, a romantic version from 1801 and a more realistic version from 1848

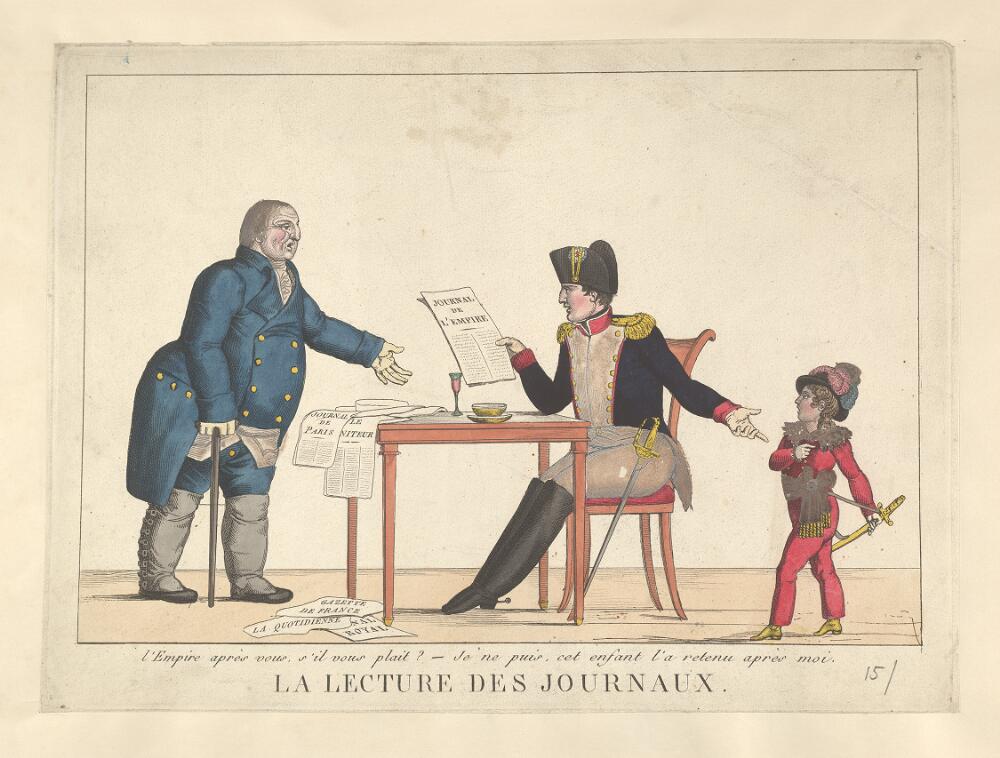

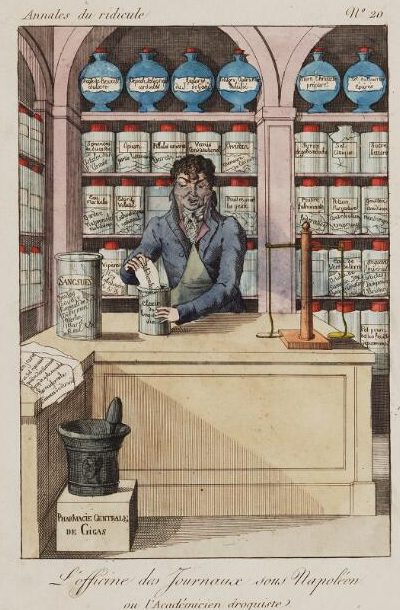

Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s key to perpetuating the war despite setbacks was ensuring the compliance of the people at home. Thus total control over French newspapers fueled the constant call for more soldiers.

Although freedom of the press existed in Enlightenment France and became an ideal during the Revolution, in the era of the Directory all formal media opposition was stamped out. In his 2002 work, Napoleon and His Collaborators, Isser Woloch writes: “Unable to solve the conundrum of when press freedom turns into license or dangerous subversion, they inscribed their ambivalent position in the constitution of 1795.” By eliminating press protections, French leaders aligned with Napoleon paved the way for a one-man military dictatorship. “The first consul had long considered freedom of the press a dangerous shibboleth, and after the experience of the Directory years he encountered scant resistance to muzzling political newspapers decisively.”[1]

The American Perspective

Despite souring Anglo-American relations on the eve of the War of 1812, American animosity to Napoleon reflected that of the British. In October of 1811, New York’s Evening Post ran an article about the emperor, asserting he was “a studious imitator of Roman policy in the business of breaking down states that thwart his views…”

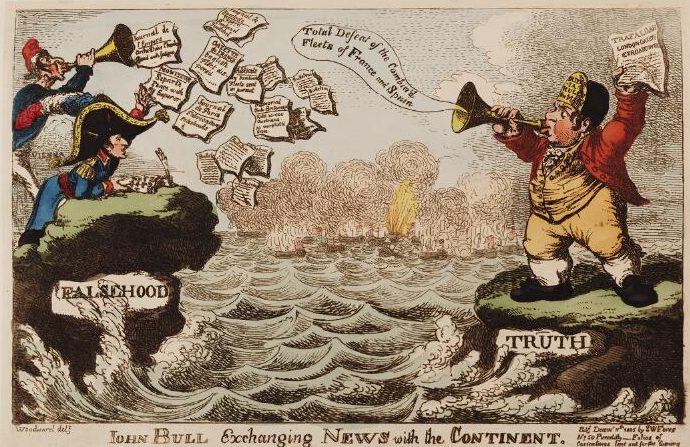

The article further described his methods, which included recognizing foreign collaborators “first to the rank of confederates, and afterwards incorporating them into the body of his empire; in dividing and beating his enemies separately, and in all that is imposing, magnificent and terrible.” The Post claimed that in France “the press is a tremendous instrument in the hands of a tyrant, and a most fearful support of his power.” In their estimation, a compliant press was where Napoleon drew his power:

Through this channel he has exclusive access to the public mind; and pours into it those systematic falsehoods… from the throne to the humblest officer of the empire; those adulatory effusions, bordering on idolatry, which tend to enervate and corrupt the best feeling; and those detestable lessons of despotism which help to rivet upon the minds as well as the bodies of men the most debasing servitude. The press under its present organization in France, instead of being the friend, is the enemy of liberty and truth…[2]

In the early nineteenth century, control of information in France contrasted the American system whose literati were divided evenly along ideological and political lines within a system of checks-and-balances intended by its founders to bulwark political inertia toward despotism. However, in Napoleonic France, in the absence of “any serious constitutional guarantees standing in his way,” the Consulate from an early point forced newspapers to close, and “coerced the sale of several others to reliable individuals, and eventually instituted formal censorship over those that remained.”[3] Without a viable press where politicians were held accountable for their actions, the French system gravitated toward military despotism.

To American observers, Napoleon personified the United States’ potential march toward empire at the expense of “the liberties of the world.” Critics contrasted what the French nation under Napoleon had become to their own nascent republic. The Hartford Courant noted that France was a nation without “freedom of speech and the press, the protection of property, of personal liberty,” and other rights Americans had fought to defend. Even with the disadvantage of late news from Europe, it was easy to see how the system had sown the seeds of destruction over the old continent. “A few years have sufficed to recruit strength after the most disastrous wars.” The movement towards despotism in France, according to The Courant, seemed to be in the “the exuberance of the [French] population, the genius of the people, whether for policy or for war… he who directs them, at will, must always be considered as the most dangerous enemy to other nations of the earth.”[4]

“Dark Age”

In 1810 the New York’s Evening Post called it a “Dark Age,” and commented on a Napoleonic decree for the “suppression of printing” in France. The newspaper’s editors were decidedly against the First French Empire. To them it was designed “to reduce mankind to a state of barbarism, that tyrants can more easily rule them.”

The Post warned that the seeds of such a system fueled by the mass manipulation of ignorant citizens had already been planted on the shores of America. “The system of democracy in this country, goes hand in hand with Bonaparte’s system of tyranny in Europe. Ignorance is supported, and knowledge and civilization are disregarded and discouraged.” In their opinion, it was essentially a matter of time before the United States mimicked what Napoleon was doing in Europe:

The most ignorant and abandoned of mankind are raised to places and offices of trust, while the enlightened and candid are neglected and oppressed. Our government have not yet suppressed information by interdicting the press, but the people have done everything to keep themselves in ignorance. …This kind of system lends to riot and anarchy – anarchy leads to absolute despotism, and ignorance fits the people to bear that despotism. So that we find our country not far behind those of Europe in the road to darkness as many may imagine. We are ignorant… and we want nothing but a Bonaparte to reduce us to as a complete state of slavery, as that which all Europe now groans.[5]

[1] Isser Woloch, Napoleon and His Collaborators, The Making of a Dictatorship (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002), 206.

[2] Evening Post, New York City, October 19, 1811.

[3] Woloch, Napoleon and His Collaborators, 206.“By 1811, only four daily newspapers were appearing in Paris, all virtual instruments of the government.” (Ibid. 207)

[4] Hartford Courant, February 7, 1810.

[5] Evening Post, New York, August 28, 1810.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.