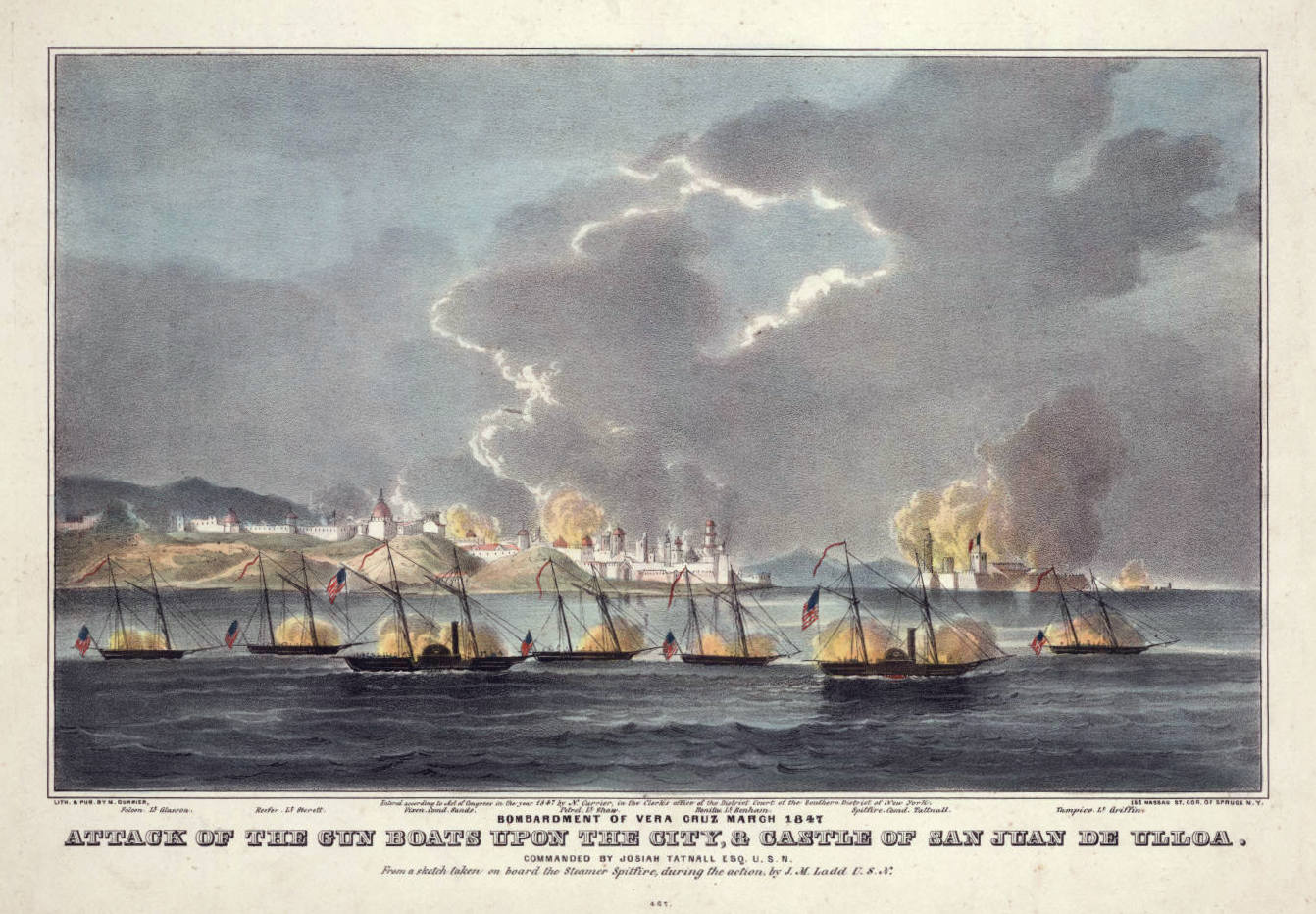

Bombardment of Veracruz by N. Currier, 1848

Many young men, who are the pride of their friends, and the hope of their parents, will return home to bring down their grey hairs with sorrow to the grave. Like causes produce like results, and nine-tenths of the inmates of our penitentiaries, and criminals whose outrages shock humanity, terminated their career in the path that is crowded here to excess by our officers. I say nothing about the common soldier. My desire “to see the world and study mankind” never yet has induced me to visit the “dark places of the earth”, or the purlieus and sinks of villainy, as shadowed forth in this city. Vice… makes us abandoned to all restraints of society, and many who are now here, that were an honor to our country, would doubtless, if they were sailors turn pirates, when this war is over; but as it is, they will return home to add to the number of those who are a curse to any community. I do not wish you, Mr. Calhoun, to think that I set myself up as a regulator of other men’s morals, or profess the spirit of the Pharisee, but the outrages here at times, would make any man reflect, who is not drawn within the vortex of dissipation. What is to be the result of it, God only knows.[1]

Captain John G. Tod, Mexico City, 1848

Born in 1808 near Lexington, Kentucky, John Grant Tod, the youngest of nine children born to pious immigrants from Scotland, left home at seventeen. Like many during the early nineteenth century living in the Mississippi River watershed, Tod traveled downriver on a flatboat seeking opportunity and adventure in the thriving port of New Orleans. For whatever reason other than studying mankind and seeing the world beyond the shores of America, Tod enlisted in the small Mexican Navy, which at the time plied the gulf coast from Texas to the Yucatan peninsula. A few years later, a more experienced Tod joined the U.S. Navy, was commissioned a midshipman, and sailed a training ship in the Caribbean until the tropical weather ailed him and was medically discharged in 1836 – the year the Republic of Texas won its independence. Like many Americans inspired by the Lone Star Republic, Tod would make Texas his cause. “If I obtain my commission,” he wrote fellow patriot William Green Hill in 1837, “it will be my pride to do my duty in every situation that my country places me. My greatest honor to prove myself worthy of the interest shown by my friends. My glory in defending the rights and advancing the liberties of our common country.”[2]

Naval Service and Pursuit of Opportunities

In 1838, a year after enlisting in the Texas Navy, Tod was appointed to the position of inspector at the naval headquarters in Galveston. A year later, as a commander, he was in charge of the entire station – a testament to his abilities and service to the upstart republic.

In the early 1840s, Tod resigned his commission and went to Washington DC to advocate for the annexation of Texas to the United States – an act that finally occurred in late 1845 after the presidential election of James K. Polk. Soon after the Mexican-American War began, Tod once again entered the service as a quartermaster agent at New Orleans and Brazos Santiago – the forward supply depot at the mouth of the Rio Grande. In 1847, at the height of the war, and around the same time that General Winfield Scott and the U.S. Army conquered and occupied Mexico City, Tod resigned from the service in the hopes that he would win a lucrative government contract for mail service between New Orleans and Veracruz – Mexico’s main port and outlet to the world. When this failed to materialize, Tod left for Mexico once again in search of opportunity.[3]

Critique of Moral Decay

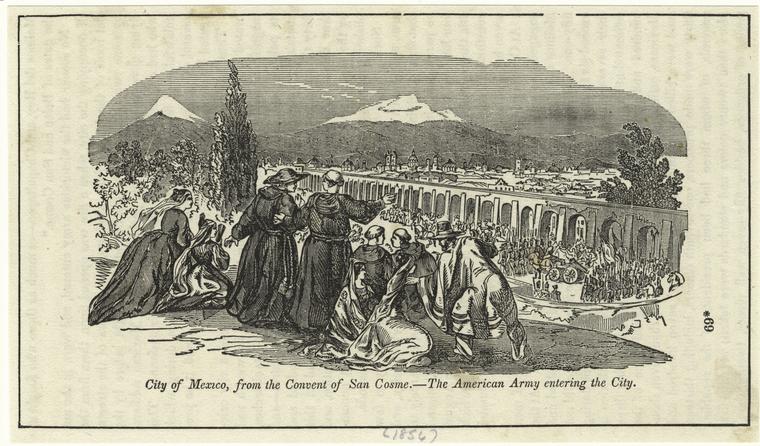

In the 1840s Mexico City was one of the oldest and largest cities in the western hemisphere. However, in 1848 it was also the operational home of the U.S. Army of occupation commanded by General Winfield Scott. Scott was known for being a strict disciplinarian regarding the protection of noncombatants and property during the war, but his laissez faire approach to off-duty recreational activities of the officers and soldiers offended Tod’s conservative sensibilities.

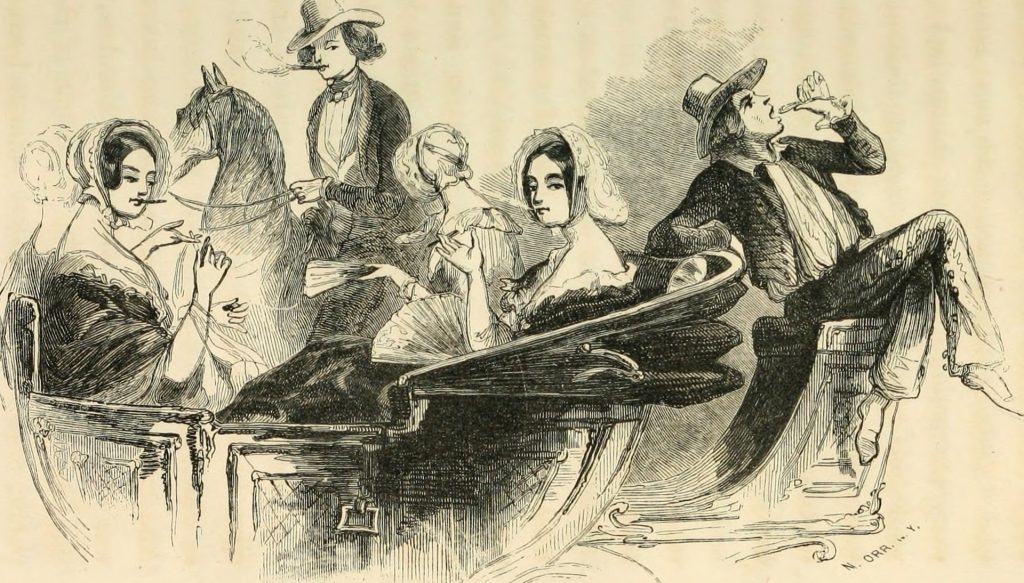

Writing to South Carolinian senator John C. Calhoun, Tod wrote, “If you were in this city for one day, to see and observe the dreadful state of morals amongst our troops, you would not be surprised at the outrages committed here daily against society and humanity.” Of particular distaste to Tod was the fraternization of officers and soldiers with Mexican women in the gambling houses and drinking establishments:

I have always, on proper occasions, denounced the course pursued here by our authorities, in legalizing gambling houses, and places of resort called “Ball Rooms”, which are mere receptacles for a profligacy and corruption unknown, since the downfall of Venice! Not one decent Mexican Lady would dare ever to think of going to a ball here? – And no American gentleman, according to the acceptation of the word at home. Yet the rooms are crowded with our officers night after night. As for the gambling houses, there is a constant crowd, Sabbath as well as week days, around the tables – Colonels, Majors, Captains, Lieutenants, grey headed men and beard-less youths, married and single: hundred[s] of whom keep women, and openly appear in public with them. These things, with drinking, brings down the standard of our morals to a degree, below the conception of Americans at home. Our Generals, and superior officers looking for political preferment at a future day, do not possess the firmness and moral courage sufficient to discountenance, and rebuke the vicious habits, that are degrading the character of our flag: and that is destined in time to roll back a tide of vice and corruption upon our country, that will be felt by many, when the glory of this war has departed… All resulting from vices that have been winked at and tolerated by those to whom are entrusted the honor of our flag.[4]

[1] John Franklin Jameson, ed., Correspondence of John C. Calhoun, vol. 2 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900), 1165. John G. Tod to Senator John C. Calhoun, April 5, 1848.

[2] Alex Dienst, The Navy of the Republic of Texas (Temple, TX, 1909), 74. (From Houston) May 25, 1827; Uli Haller, Texas State Historical Association (1976): https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tod-john-grant-sr For the U.S. government’s pre-Civil War reinstatement of Tod to the rank of Captain, see: “Captain John G. Tod. (To accompany Bill H.R. No. 615.)” Washington DC: Committee on Naval Affairs, May 29, 1858.

[3] Uli Haller, Texas State Historical Association, 1976.

[4] Jameson, ed., Correspondence of John C. Calhoun, vol. 2, 1164–5. John G. Tod to Senator John C. Calhoun, April 5, 1848.

About the author

Based in South Korea since 2008, Benjamin J. Swenson is a professor at Hoseo University in Asan. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed 19th-century Euro-American military history. His work has appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his most recent, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare (2023), was published by Pen & Sword. Its follow up, Wars of the Mexican Gulf, will be published in 2024. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.