Battle of Navarino, 1827, the Greek War for Independence

The Greek War of Independence (1821-1829) against the Ottoman Empire drew so much popular support in Europe that eventually Great Britain, France, and Russia were compelled to lend it military support. On the opposite side of the Atlantic, U.S. statesmen immediately petitioned the government to recognize the First Hellenic Republic despite a foundational tenet to avoid foreign “entanglements” by intervening in European affairs.[1]

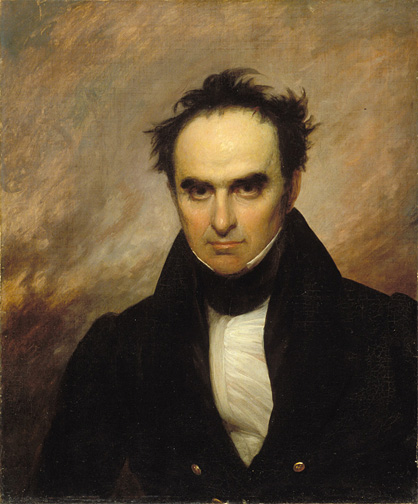

Daniel Webster, who would later become one of the three “Great Triumvirate” Antebellum-era Senators, noted in an 1823 speech that the Greek navy – which began using small ‘fire ships’ to counter Ottoman naval superiority – excelled in “a mode of warfare in… of such distinguished skill and bravery, as would draw applause upon the best mariners in the world.” One of those Greek mariners included the first female admiral Bouboulina. More importantly, Webster noted that the Greeks “awakened a sympathy throughout Europe and throughout America; and they have formed a government which seems suited to the emergency…”[2]

Another advocate for Greece was the future diplomat and Massachusetts governor Edward Everett. An accomplished scholar of the Classics, Everett worked through the magazine The North American Review on behalf of the Greek “Struggle” (Agonas) – a movement to overthrow four hundred years of Ottoman rule. Everett not only compared the war to the American Revolution, he invoked themes from ancient conflicts between Greece and Persia. “To say nothing of the valiant heroes who fight beneath the banners of a Coke and a Blackstone, the scholars of the East are in arms, and like Homer’s Greeks, ‘breathing rage in silence,’ are advancing, with Achilles at their head, from a thousand hills.”[3]

U.S. Maintains Neutrality

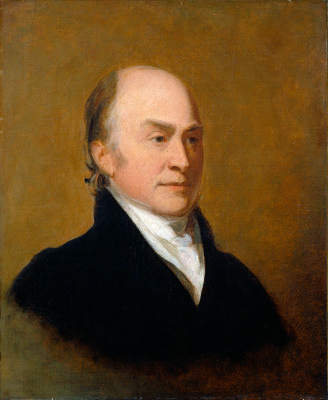

Even though Americans supported the cause, U.S. did not officially recognize the revolutionary government. Andreas Luriottis, an envoy to London from the Greek Provisional Administration, sent a letter to the United States seeking diplomatic recognition while noting that the new Greek “organic law assimilates to that [U.S.] constitution under which your nation so happily and securely lives.” In response, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams outlined his concerns to the U.S. minister there that formal assistance to the Greeks “would constitute [the U.S.] in a state of war with the Ottoman Porte, and perhaps with the Barbary powers” – which the U.S. fought from 1801 to 1805, and again in 1815. Nevertheless, Adams responded warmly to Luriottis:

The sentiments with which he [President Monroe] has witnessed the struggles of your countrymen for their national emancipation and independence… are cordially felt by the people of this Union… But, while cheering with the best wishes the cause of the Greeks, the United States are forbidden… from taking part in the war…[4]

After his presidency, the positive outcome of the war so inspired John Quincy Adams that he tried to write its history “to show that the Ottoman nation is the bitterest enemy to the human race, and the severest scourge that was ever sent by Providence to chastise mankind…”

However, due to the conflict’s complexity and the lack of detailed sources in the United States, Adams abandoned the project. “I selected and read over the whole succession of extracts from the English newspapers relating to Greece and to the war between Russia and Turkey. Of the military operations I found nothing but lame accounts of small affairs…”[5] Formal recognition was equally anticlimactic but finally achieved in 1837. Although the U.S. only tacitly supported the struggle, it was not until World War One that America involved itself in European wars.

[1] George Washington’s Farewell Address, September 19, 1796.

[2] “Mr. Webster’s Speech on the Greek Revolution” (Washington DC, J.S. Meehan: Library of Congress, Miscellaneous Pamphlet Collection, 1824), 44.

[3] George Bancroft, Edward Everett, The Grecian Wreath of Victory (New York: W.E. Dean, 1824), 29.

[4] The United States Gazette (Philadelphia), January 6, 1824. Richard Rush, U.S. Minister to the UK to John Quincy Adams, London, February 20, 1823 (letter from Andreas Luriottis attached); Adams to Rush August 18, 1823 (letter to Luriottis from Adams attached).

[5] Charles Francis Adams (ed.), Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848, Vol. 8 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1874), 202-3. March 18, 1829.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

2 thoughts on “When America Avoided Entanglements: The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821-1829”