For hundreds of years European explorers braved the Arctic Sea’s treacherous waters in search of an elusive “Northwest Passage” – a route to Asia and Cathay circumventing the Indian Ocean and treacherous horn of South America. The Vikings of Iceland and Greenland were the first to ply the frigid American waters beginning in the late 10th century but colonized and exploited regional resources rather than look for a route to the Far East.

John Cabot and William Weston’s voyages (1497-1500) from Bristol navigated the seas Vikings pioneered, but it was not until the early 1600s that Henry Hudson (under the Dutch East India Company) formally embarked upon a series of journeys to specifically find the fabled route. Hudson’s last voyage in 1611 on behalf of the British East India Company resulted in mutiny, and he was set adrift in a small boat with seven loyal crew members never to be seen again. Beginning In 1612, William Baffin unsuccessfully attempted to find the Northwest Passage by sailing through the Hudson and Davis straits. Others, like Vitus Bering (1681-1741) and James Cook (1728-1779), looked for the passage from the Pacific side of North America.[1]

The Modern Quest, 1845-1906

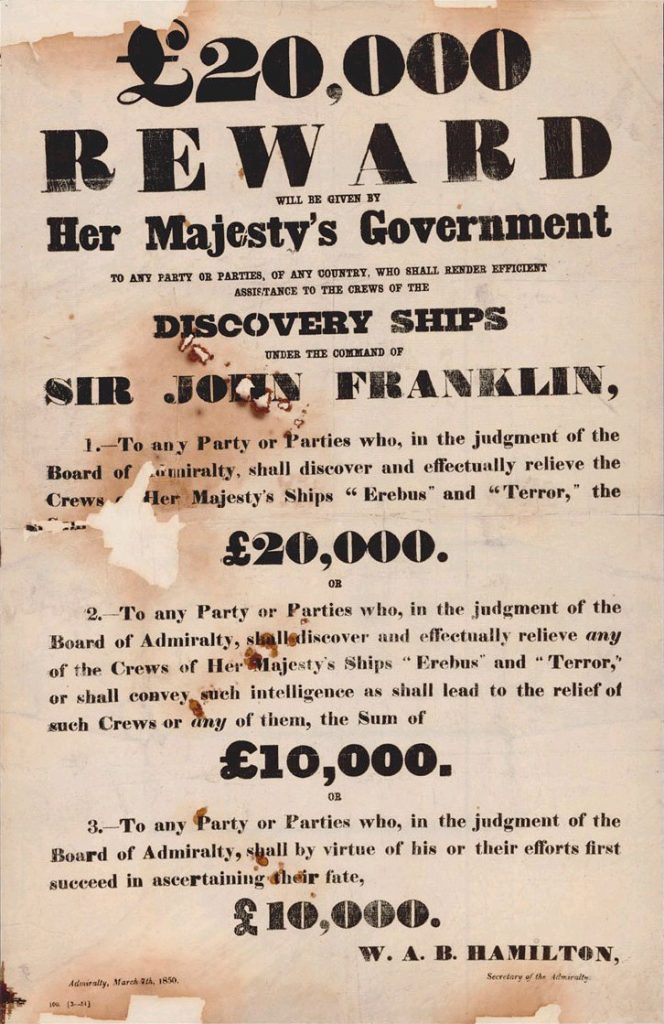

The modern search for the passage is marked by the tragic expedition under the command of Captain Sir John Franklin (1786-1847), which left England with two ships and a total of 129 men in 1845 and mysteriously disappeared.

Roald Amundsen (1872-1928), a Norwegian explorer who became the first to successfully traverse the passage between 1903 and 1906, wrote admiringly of Captain Franklin: “Of all the brave Britishers who for 400 years had given freely of their treasure, courage, and enterprise to dauntless but unsuccessful attempts to negotiate the Northwest Passage, none was braver than Sir John Franklin.”

Amundsen noted that one of Franklin’s harsh return voyages “thrilled me as nothing I had ever read before. …for three weeks he and his little band had battled with the ice and storms, with no food to eat except a few bones found at a deserted Indian camp…”[2] At the time, Franklin’s well-prepared attempt to traverse the Arctic was touted as the most technological ever:

A great portion of the crews, as well as the officers, are from the north country… Double pay has been allowed… and besides an abundant supply of provisions for three years (that may last for four), there has been furnished a full supply of clothing, blankets, and shoes. The great superiority of this expedition will possess over its predecessors…[3]

Contrasted with a large crew and two boats, Amundsen’s small sloop Gjøa was manned by merely six men including the captain. How else did Amundsen’s expedition differ?

One answer can be found in Amundsen’s memoirs, where the Norwegian gathered information based on numerous “expeditions sent out by the British government in attempts to rescue Sir John Franklin, who had never come back…” Amundsen noted that Franklin “and his men had perished from starvation—oddly enough, at a spot where, when we reached it, we happened to find an abundance of game on land and fish in the water.”[4] Out of deference to his predecessor Amundsen did not mention that Franklin’s tragic mistake after becoming icebound was to stubbornly cling to the very things that made him less mobile. In other words, the British would not abandon their ships. In contrast, Amundsen made a point of wintering with local Inuit when the opportunity arose and learned from them the best way to survive the Arctic’s unforgiving climate.[5]

[1] See: James P. Delgado, Across the Top of the World: The Quest for the Northeast Passage (Vancouver: D&M Publishers, 1999)

[2] Roald Amundsen, Roald Amundsen – My Life as an Explorer (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927), 2.

[3] Glasgow Herald, May 23, 1845.

[4] Amundsen, My Life as an Explorer, 61.

[5] See: Stephen R. Bown, The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen (Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2012); Paul Watson, Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017).