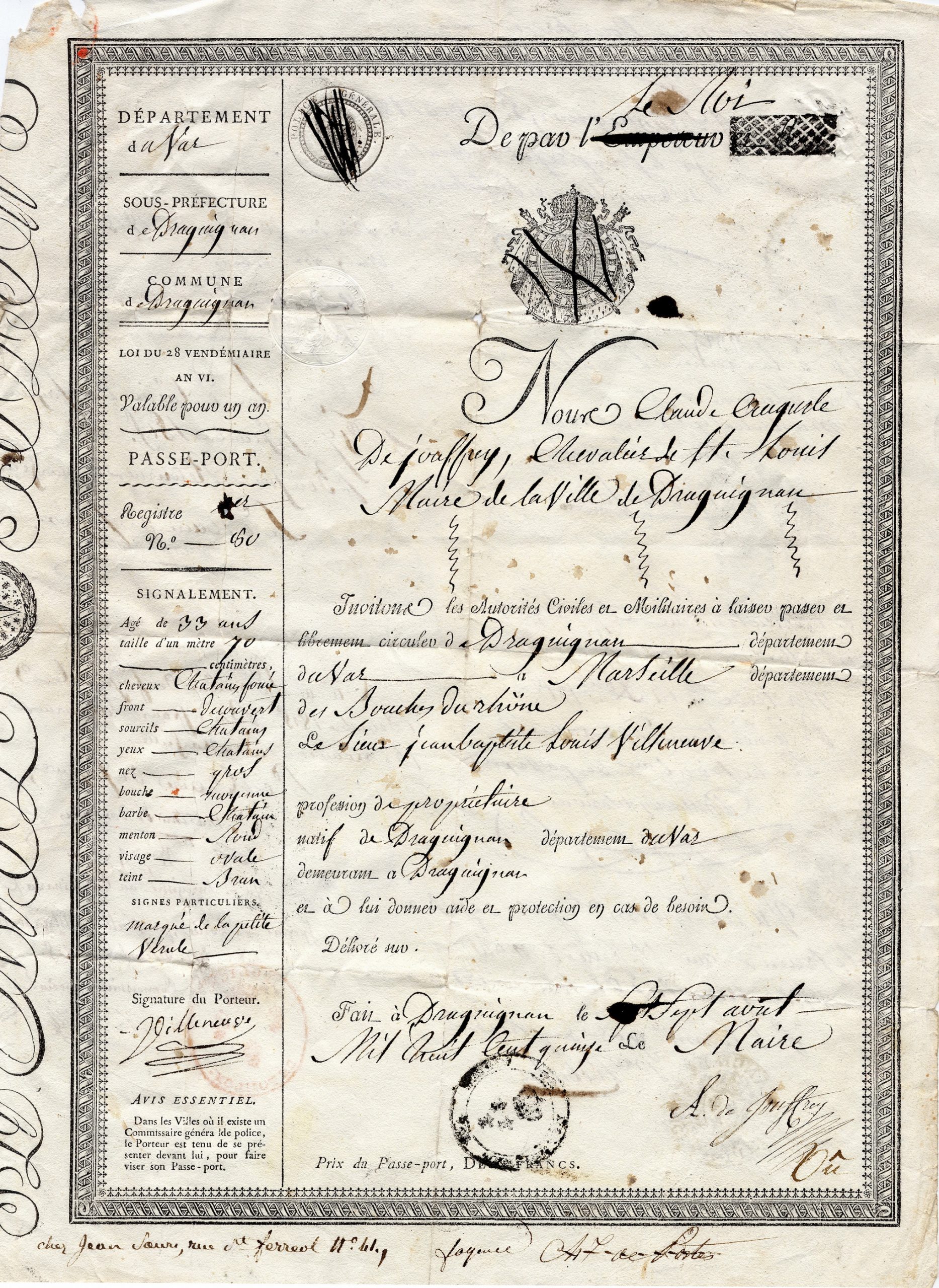

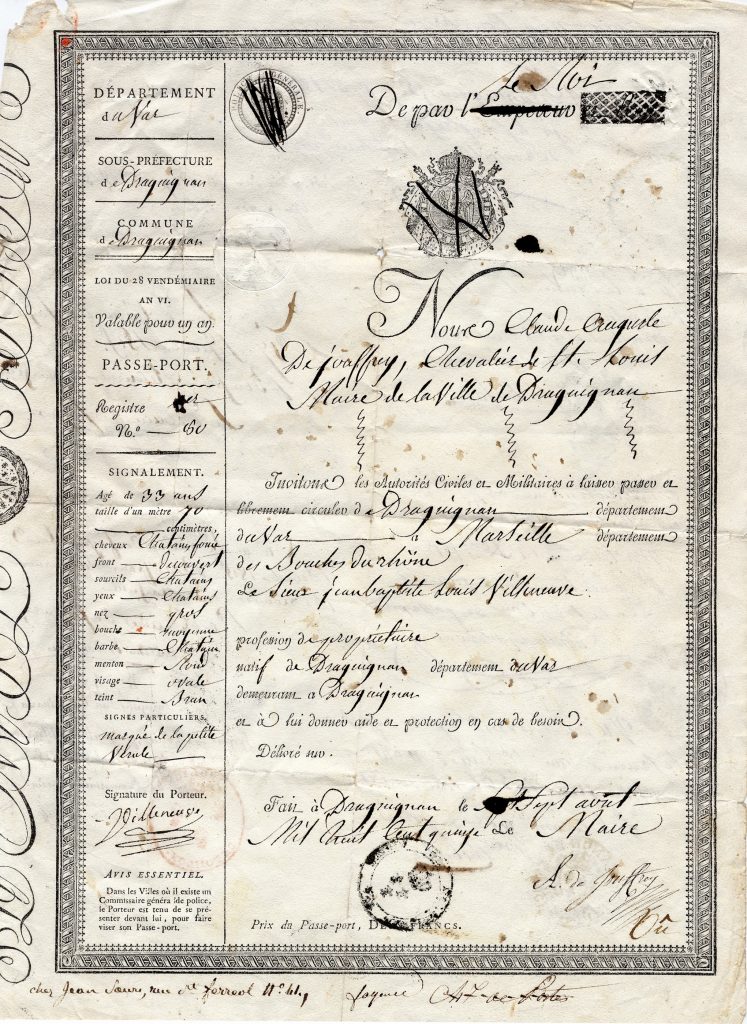

One of the many ways Napoleon Bonaparte attempted to control populations was the mandating of passports. Passports in various forms have been around for centuries but not in the manner most people associate with them today.

(Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Etymologically the term “passport” originated during the medieval period when foreign travelers and merchants were required to obtain permission to pass through a city gate or “port.” For a long time, harbors used for international trade generally did not require such documents but travel into the interior of a country was restricted. In the eighteenth century, mercantilist-minded governments increased the use of such documents – particularly during periods of war. During the French Revolution (1789-1799), passports were used by the regimes to better control people coming and going from towns and cities both within and without France. By the time Napoleon began his infamous blockade of British goods to continental Europe, passports had become a common requirement in cities and seaports.[1]

Counterinsurgency, Control, and Collaborators

During the French occupation of Spain military authorities facing an unprecedented hostile population supporting a guerrilla insurgency began forcing people to use passports or “cards of security” to travel between towns and cities. This program – designed as part of a multifaceted counterinsurgency operation – was implemented throughout the country. In the Valladolid region, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessieres issued thirteen repressive decrees in the summer of 1811.

“No inhabitant can remove from his township, without being provided a passport…” Other decrees warned that anyone giving “asylum to any individual unprovided with a passport or card of security” would be arrested. To add to the seriousness of the decrees, the marshal warned communication with “brigands shall be punished with death.” Like other French governor-generals in occupied Spain contending with guerrillas, Bessieres tried to restrict the movement of anyone who could potentially be aiding the resistance:

“Domicilliary visits shall be made, in pursuance of the orders of the Commandments of Towns, at periods of which they shall deem proper; every individual unprovided with a card of security, shall be immediately arrested and sent to prison; the public functionaries alone are excepted from the order.”[2]

Other areas under French control implemented passport controls. In Poland, for example, travel was also restricted. The Morning Chronicle of London reported that they had “heard a great deal about preventing persons from traveling from one part of the kingdom to another without passports from Napoleon. …it is directed, no doubt, principally against merchants and foreigners.”[3] Unsurprisingly, passport restrictions were also directed at people attempting to leave France. In 1809 in the Confederation of the Rhine (a client state of Napoleon) the Grand Duke of Frankfurt issued a decree forbidding French citizens from entering the city from the “left banks of the Rhine” River. The police were instructed to watch for violators and arrest anyone traveling without official permission from Parisian authorities:

“The French Government have made reiterated representations, that in the country of the Confederation bordering upon France, desiring all necessary measures should be taken to prevent the emigration of French subjects, who set out with their families… to pass in and through the territories of this town, notwithstanding any foreign-passports they may have, unless they can prove their emigration is expressly authorized by the Minister of Police at Paris…”[4]

While Napoleon successfully managed to control France and most of the major cities of Spain, the shortage of collaborators in the towns and villages to enforce the passport program meant that guerillas and others supporting the insurgency could move relatively undetected. Reprisals against those helping the French occupy Spain also reduced its efficacy. Ultimately, Napoleon’s passport system was more successful in controlling people living closest to the administrative heart of the First French Empire than those in the occupied regions on the periphery.[5]

[1] See: John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

[2] Hartford Courant, October 23, 1811. Quoted from the London Courier August 30, 1811.

[3] The Morning Chronicle (London), January 3, 1811.

[4] The Times (London), October 12, 1810.

[5] See: Isser Woloch, Napoleon and His Collaborators: The Making of a Dictatorship (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002).

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

3 thoughts on ““Public functionaries alone are excepted”: Napoleon’s Passport System in Europe”