Frumentarii on Trajan’s Column, 113 AD

The security of the Roman Empire relied upon the three divisions of the ancient law and order – the urbani, the vigiles and the frumentarii. Urbani was the force that handled criminal and political cases. They were responsible to the praefect of the city. When the praefect issued regulations, urbani needed to insure obedience to these regulations. They usually operated inside the great Roman markets like the Campus pecuarius, the Forum boarium, the Forum suarium and others. Urbani were based in the vicinity of the Forum suarium, in the barracks. They were founded in 24 AD by the Emperor Augustus who wanted to protect the welfare of the city. The vigiles were also established by Augustus. They had a similar role as today’s police officers or firemen and were inferior to the urbani. Founded in 6 AD, also by Augustus, they acted as a night watch and their duty was to prevent fires. Therefore, they were a sort of ancient firemen. These nocturnal police numbered more than 7000 men. They received orders from the Praefectus Vigilum who had an “office” on the location of today’s Piazza dei Santi Apostoli in Rome.

Ordinary Men for Special Tasks

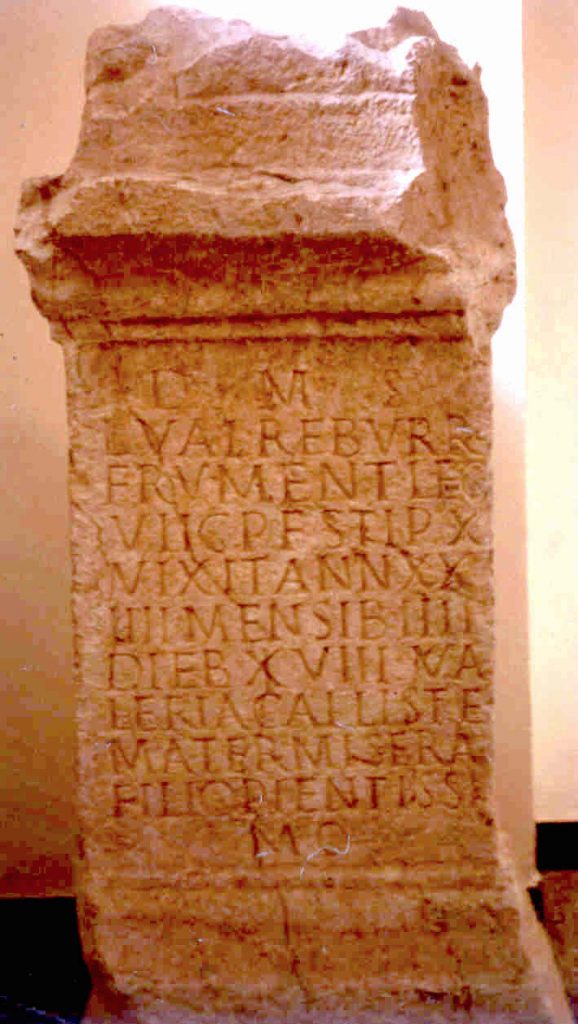

The urbani and the vigiles were the forces that handled typical, everyday cases. But, those who were recruited for special tasks were frumentarii. Frumentarii were a sort of commissariat of Ancient Rome, secret agents and detectives. While the former two forces were policemen and firemen, the job of frumentarii was to carry dispatches, to spy, to inform, and also to arrest suspects if needed.

Some frumentarii acted similar as today’s detectives. The frumentarii were founded by the Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD. The situation in the Empire during his reign clearly required the quality intelligence service. It wasn’t easy to create a sort of bureau, so Hadrian had the solution. He gave these tasks to frumentarii – the wheat collectors. Their day job was an excellent cover for the activities Hadrian wanted them to do – spy on Roman citizens. Thanks to frumentarii, Hadrian was well-informed as to what is happening at the court, among his family and friends, and in general, in the whole Empire.

During the persecutions of the Christians, frumentarii were the chief agents. Among the duties, they also had the prisoners of the state under their supervision. There is a story that Cuodomeo, King of the Germans, after he was made prisoner at the Battle of Strasbourg and brought to Rome, died at their hands. Their superior was an officer called princeps, an ancient version of the 20th century commissar. Princeps also commanded peregrini – the strangers. Peregrini had a similar role as frumentarii. Both frumentarii and peregrini were dissolved during the reign of Diocletian who replaced them with agentes in rebus.