Despite overtures to the Catholic Church by American political and military leaders during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), the need to enforce discipline in theater was paramount to the U.S. Army’s success. When more than seventy Irish-American deserters, known as the Saint Patrick’s Battalion (San Patricios), were captured by U.S. forces in late August of 1847 following the Battle of Churubusco on the outskirts of Mexico City, they were summarily court-martialed. The former U.S. soldiers had been induced by Mexican incentives of free land and money to switch sides and fight for Mexico. Eventually their numbers reached a few hundred. They also fought well and were therefore doubly hated by U.S. Army officers. In contrast, the San Patricios are remembered as heroes in Mexico.

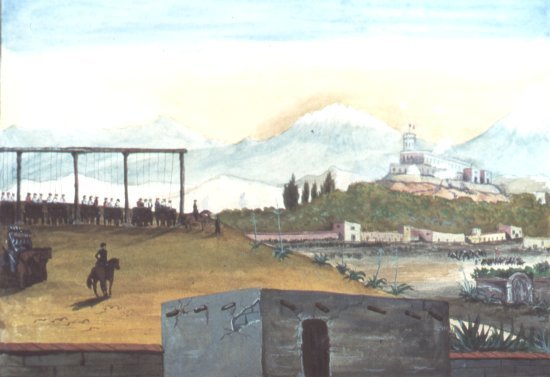

A Symbolic Hanging at the Gates of Mexico City

General Winfield Scott, the commander of the U.S. Army’s campaign in central Mexico, made an example of the soldiers’ desertion by conducting two court-martial proceedings while the army threatened the gates of Mexican City. Fifty soldiers were sentenced to death by hanging, thirty of whom received their punishment on September 13 at Chapultepec Castle as the U.S. Army rode into the capital. Colonel William Harney carried out the execution at Chapultepec, and even hung Francis O’Conner, who had both legs amputated the day before due to injuries.

George Ballentine, a British enlistee in the U.S. Army, gave an account of the event: “I sincerely pitied these poor fellows, many of whom I had reason to believe had been driven to the foolish step they had taken by harsh and cruel usage, operating on a sensitive and excitable temperament.” Ballentine believed the young Irish immigrants made their fatal decision due to cruel officer discipline. “The barbarous treatment which soldiers sometimes received from ignorant and brutal officers… would seem almost incredible.” One punishment meted out for “trivial offenses” included tying wrists and gagging. Ballentine noted that at the Chapultepec battle the deserters specifically targeted U.S. officers: “The large number of officers killed in the affair was also ascribed to them, as for the gratification of their revenge they aimed at no other objects during the engagement.”[1]

In a symbolic gesture of American ire towards the condemned the majority of the San Patricios were hung the moment the U.S. flag was raised over Chapultepec’s walls. Scott reminded his troops thereafter, to ensure that “all our soldiers, protestant and catholic, remember the fate of the deserters at Churubusco.”[2]

The U.S. occupation newspaper in Mexico City, The American Star, was not as sympathetic as Ballentine. Many of the soldiers who defected prior to the official declaration of war (May 13, 1846) had their sentences commuted to fifty lashes. This included their leader, John Patrick Riley (O’Riley), who was branded with a “D” on the cheek – a common punishment for desertion. The U.S. Army newspaper lamented that Mexican leaders had “stooped to the low business of soliciting desertion from our ranks, and had succeeded in seducing from duty and allegiance the poor wretches who had to pay so dearly for their crimes.” Even though Riley escaped the same fate as his comrades, The Star’s editors believed that “all that could be awarded him was well administered.”[3] Indeed, many readers back in the United States felt the same regarding those who had turned on their former friends. One North Carolinian newspaper was even less gracious towards the “traitors” who “brought dishonor upon the chivalric nation of their birth.” The “‘unfortunate Irish’ …who, after receiving the bounty of our government and the protections of our institutions… deserted to the Mexican Standard [flag]. Their fate, death, is consonant to the laws of war and agreeable to justice and self-preservation.”[4]

[1] George Ballentine, The Mexican War, By an English Soldier. Comprising incidents and adventures in the United States and Mexico with the American army (New York: W.A. Townsend & Company, 1860), 255-256.

[2] The American Star, Mexico City, September 23, 1847.

[3] Ibid. September 20, 1847. See also: Edward S. Wallace, “The United States Army in Mexico City.” Military Affairs 13, no. 3 (Autumn, 1949), 160-161.

[4] The Tri-Weekly Commercial, Wilmington, North Carolina, October 5, 1847.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

Ben, thank you for that article,–I’ve been wanting to learn more about this topic,–and your information is different from what I’ve read in the past.