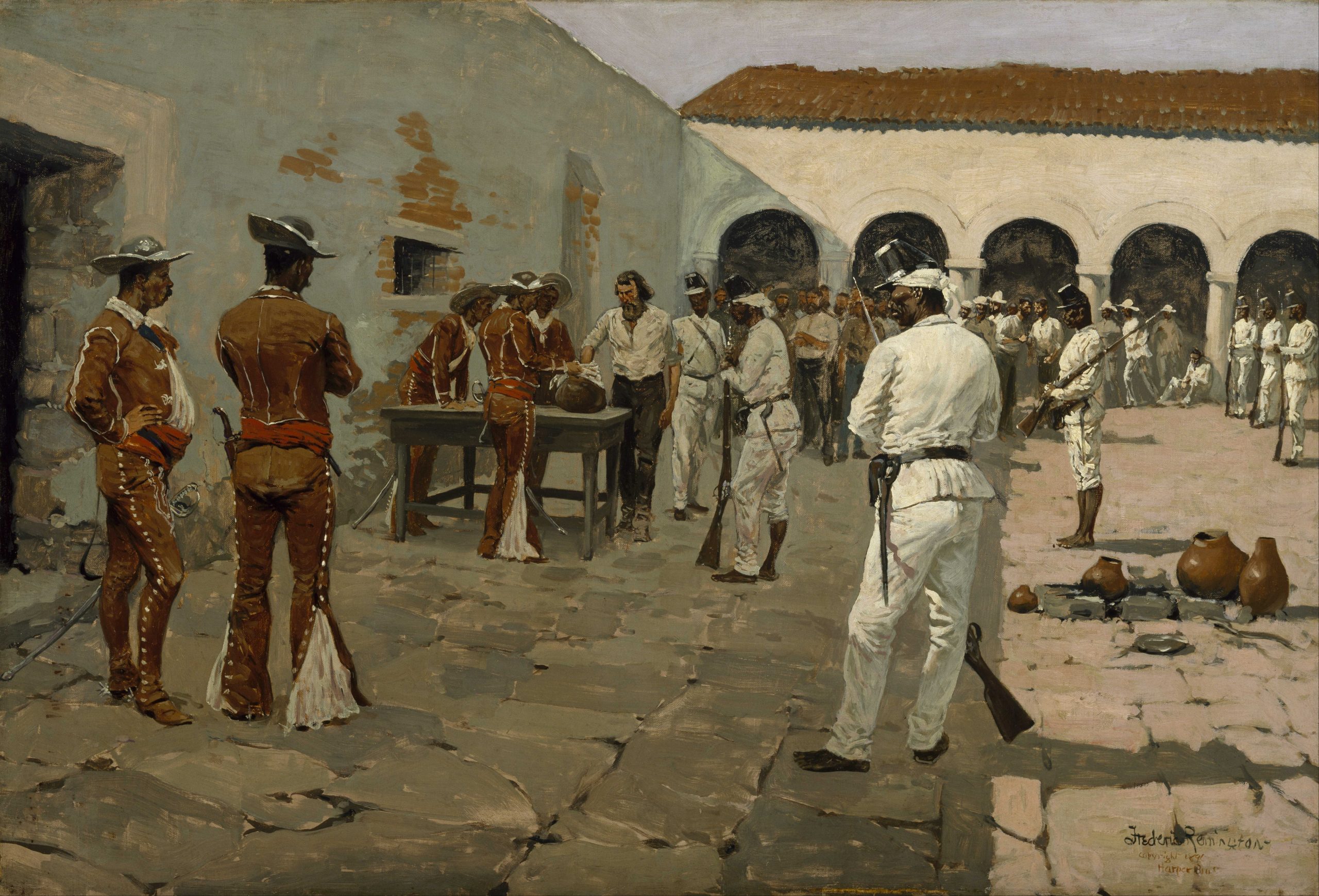

The Mier Expedition- The Drawing of the Black Bean by Frederic Remington, 1896

One of the many reasons Texans fought fiercely against the Mexicans during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) was to avenge past injustices they believed were committed against them in the years preceding the annexation of the Republic of Texas to the United States. One such instance was the Black Bean Lottery resulting from the failed Mier Expedition in late 1842 to the so-named town opposite the Rio Grande. Writing in 1909, author Fanny Chambers Gooch, better known for her 1887 work Face to Face with the Mexicans, noted in the preface of her book, The Boy Captive of the Mier Expedition, that although she “had no desire whatever to arouse a feeling of bitterness or antagonisms” she nevertheless chronicled a chapter in the life of John Christopher Columbus Hill (1828-1904), who as a young teenager participated in the Mier debacle along with his father and brother. Shortly after his capture, Hill was adopted and provided an education by Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna while most of the other 242 Texan prisoners of war were forcibly marched more than 650 grueling miles to Mexico City and imprisoned.

The bitter irony in Santa Anna’s benevolence towards Hill, however, lay in the fact that it was he who ordered the execution of Hill’s comrades after their attempt to escape while en route to the capital. Although the death sentence was reduced to seventeen men by forcing 176 of those recaptured to randomly draw black beans from a clay jar, the episode became a rallying cry among Texans during the U.S.-Mexican War.[1]

Mier Expedition

In September of 1842 Texans and Mexicans engaged in a series of skirmishes near San Antonio resulting in the deaths of three dozen Texans. In response, that November the Texans organized a retaliatory expedition of several hundred soldiers and pushed through Laredo towards Ciudad Mier – located on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande.

In late December, when more than three hundred Texans led by Colonel William S. Fisher crossed the river and entered the town, they realized it was garrisoned by a sizeable force commanded by General Pedro de Ampudia. Thomas J. Green, captured in Mier on Christmas Day after a deadly firefight, chronicled the capitulation and forced march into the heart of Mexico. Before the prisoners set out mid-January, Green and Fisher penned a note to their comrades:

It has fallen to our lot to become captives to the nation with which we are at war. This is the fortune of that policy; and though our condition is incident to these privations, let us bear up under them with the fortitude of men. Let us nerve our souls in that impregnable armour which lightens the weary limb, and which the steel of our enemy cannot penetrate. That immortal spirit will make us superior to our condition, and triumph over our misfortunes. …Indulge, therefore, all reasonable hope in the magnanimity of our enemy, and in that justice which is the all-pervading providence of God. [2]

Black Bean Episode

On February 11 while waylaying at a hacienda in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas 181 prisoners overwhelmed their guards and escaped into the desolate desert country. As soon as their food and water ran out, however, the group was quickly sapped of morale and strength, and all but five of the escapees were either recaptured or willingly returned to Mexican authorities.[3] When an incensed Santa Anna was informed of the escape attempt, he sent word to the commander to shoot all of the prisoners – an order that was rejected by General Francisco Mejia but replaced with decimation – which meant a “removal of a tenth” in Latin. Green explained that the Mexicans placed 159 white beans on the bottom of the clay jar first, and then added the seventeen black ones to the top of the pile in the hopes of killing as many officers as possible – as they were the ones who chose their beans before the rest of the men:

They all drew their beans with manly dignity and firmness… Some of lighter temper jested over the bloody tragedy. One would say, “Boys, this beats raffling to pieces;” another would say that “this is the tallest gambling scrape I ever was in,” and such remarks. None showed change of countenance; and all the black beans failed to depress, so did the white fail to elate. …Poor Major [James D.] Cocke, when he first drew the fatal black bean, held it up between his finger and thumb, and with a smile of contempt, said, “Boys, I told you so; I never failed in my life to draw a prize…”

Green wrote that on the day of execution, March 25, 1843, “in spirit of giant” James N. Torrey proclaimed that “‘he was perfectly willing to meet his fate; that for the glory of his country he had fought,’” and before being shot by a firing squad, turned to the Mexican officer and said, “‘After the battle of San Jacinto, my family took one of your prisoner youths, raised and educated him, and this is our requital.’”[4] That path was the similar path of John C. C. Hill, for it led to a new life far from his family and homeland.

The Separate Path of John C.C. Hill

When John C.C. Hill surrendered with his fellow Texans at Mier he was ordered to relinquish the rifle given to him by his older brother James who could not participate in the expedition. Instead of handing it over, the brash teen broke it in defiance. Paradoxically, this gesture spared him the grief of having to accompany his fellow Texans on the long trek because it was noticed by General Ampudia, who immediately took a liking to him.

Hill traveled with the general on horseback, was given a new set of clothes to “replace his own powder-scorched” rags, and was enrolled by Ampudia in a Matamoros school for several weeks under the name Juan Cristoph Colón Gil de Ampudia. The modern historian Sam Hayne notes that in Ampudia’s “dispatches to the capital, the general mentioned the youth’s bravery at Mier and spoke highly of his character and intelligence. Such praise apparently piqued the interest of Santa Anna…” As a result, Hill was personally invited to meet the president at the palace in Mexico City.[5] This meeting became a literary focal point in Fanny Gooch’s account of Hill’s experience:

But now, to face a new danger, and be subjected to the ordeal worse than death in meeting the awful Santa Anna, who would undoubtedly have him killed; all these thoughts passed through his mind. True, …but owing to the great kindness of General Ampudia… he had been as free as a bird from the moment of his coming into the presence of the General; in fact had General Ampudia been his own father, he could not have been more tender or gentle in his treatment of the boy.

Hill represented himself eloquently and honesty enough that after meeting Santa Anna his father and brother were released, and he was granted permission by his father to enroll in the Mineria – one of the more prestigious engineering schools in Mexico. The education was provided by Santa Anna, and Gooch surmised that his generosity may have been motivated by the fact that he “had no living sons” – although this was speculation. A few years after the U.S.-Mexican War, Hill was again “taken captive on Mexican soil. Love in the guise of a dreamy-eyed señorita, called to him, ‘Rindan sus armas!’ ‘Surrender.’ The surrender was complete and instantaneous.”[6] The young Hill entered Mexico to exact revenge, but in the end, he learned to live, love, and grow old in the same country he set out to conquer for Texas.

vincere est vivere

[1] Fanny Chambers Gooch, The Boy Captive of the Mier Expedition (San Antonio: J.R. Wood Printing Co., 1909), prefatory note (8); Face to Face with the Mexicans (New York: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1887).

[2] Thomas J. Green, Journal of the Texian expedition against Mier; subsequent imprisonment of the author; his sufferings, and the final escape from castle of Perote (New York: Harpers, 1845), 127-8.

[3] William Preston Stapp, The prisoners of Perote: containing a journal kept by the author, who was captured by the Mexicans at Mier, December 25, 1842, and released from Perote, May 16, 1844 (Philadelphia, G. B. Zieber and Company, 1845), 58-68.

[4] Green, Journal of the Texian expedition, 170-1.

[5] Sam W. Hayne, Soldiers of Misfortune: The Somervell and Mier Expeditions (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990), 79, 96-101.

[6] Gooch, The Boy Captive of the Mier Expedition, 228-231, 306.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.