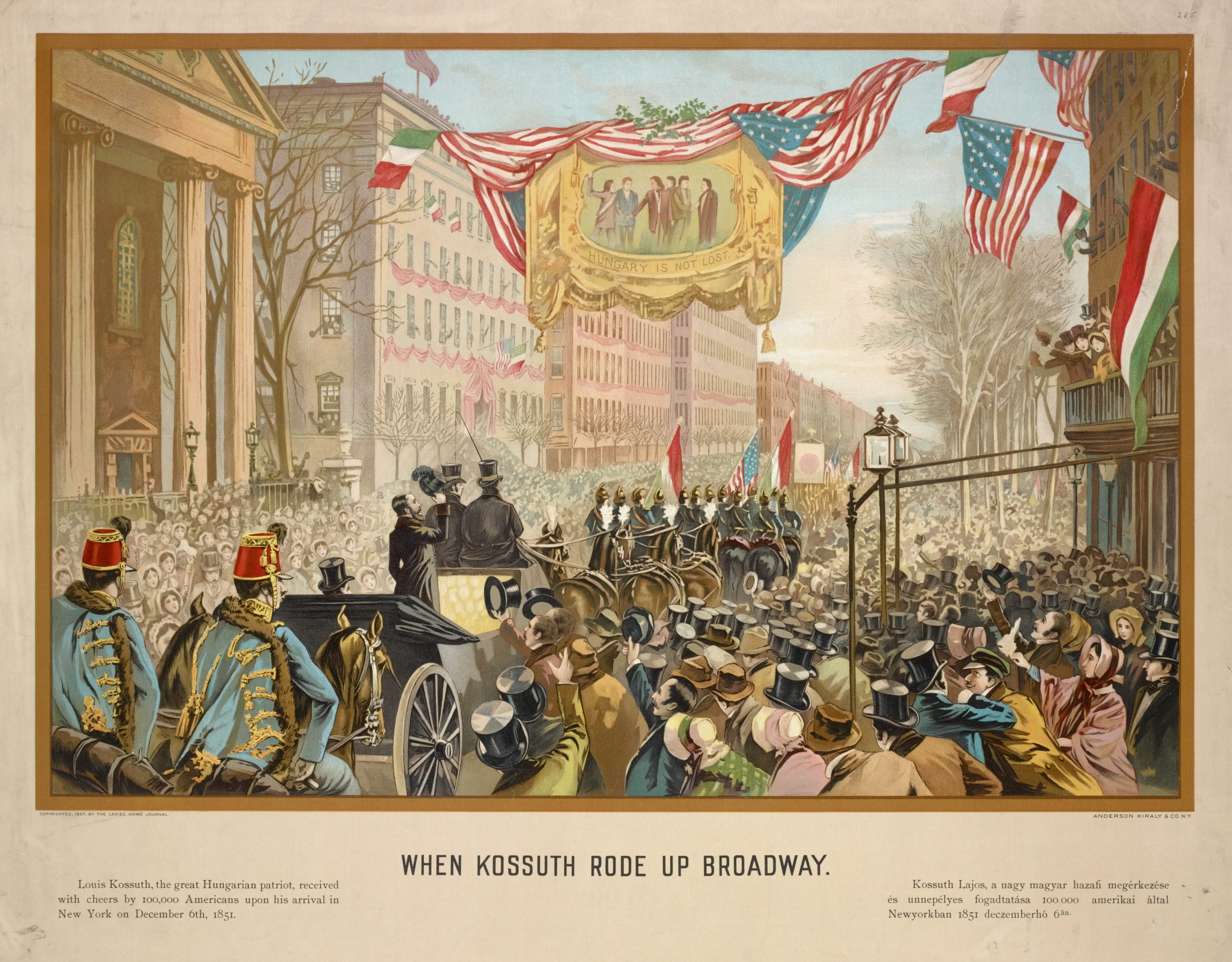

Although he was thronged by thousands of people in the principal cities of England, a key reason Hungarian nationalist and freedom fighter Lajos (Louis) Kossuth was so popular during his 1851-1852 visit to the United States was the American aversion to monarchy.

Kossuth, the figurehead of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution to overthrow the Habsburg Dynasty’s grip on that nation, was welcomed by massive crowds eager to listen to his republican-inspired orations. The New York Times noted in late 1851 that the “reception of the illustrious Kossuth… was such a scene as the world seldom beholds.” The newspaper also mentioned an ongoing public relations effort by European monarchist agents to discredit him:

“The events on Saturday indicated how utterly unavailing have been the efforts by Prussian and Austrian agents to convince the people that Kossuth did not fight for freedom, – that he struggle on behalf of the aristocracy, – and that the Emperor of Austria was the true champion of liberty and popular rights.”[1]

Detractors and Supporters

While most Americans did not believe the propaganda designed to discredit Kossuth, not everyone was impressed with him. William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator – a staunch antislavery and abolitionist Boston publication – pointed out the hypocrisy of Kossuth touring America and advocating for Hungarian independence while slavery still existed in the South:

“Behold the scenes now transpiring in New York, Philadelphia and Washington! Every influence brought to bear on Kossuth to make him bow and worship at the shrine of slavery. …He cares not about how many slaves are held by Republican America, provided the slaveholders ‘give him hospitality,’ and sympathize with Hungary.”[2]

Despite a few vocal critics, most Americans supported both Kossuth and the wave of European nationalist movements that exploded in 1848.[3] Secretary of State Daniel Webster even wrote a short book about him which included a letter of protest from the Austrian Empire’s ambassador, Johann Georg Hulsemann, claiming American statesman were criticizing Austria’s “iron rule” and representing “the rebel chief Kossuth as an illustrious man…”

Webster responded that Americans were taking a keen interest in “the prevalence on the other continent of sentiments favorable to republican liberty,” and that the alleged “propagation of falsehoods” in U.S. newspapers – which sympathized with the republican revolutions – were “wholly dependent upon” European sources. Webster’s book included an address “to the People” of the United States written by Kossuth while in exile:

“The Hungarians, more fortunate than I, who were able to reach the shores of the New World, were received by the people and Government of the United States in the most generous manner – yes, like brothers. With one hand they hurled anathema at the despots, and with the other welcomed the humble exiles to partake of that glorious American liberty more valued than the glitter of crowns.”[4]

Kossuth was honored to become the second foreigner after the Marquis de Lafayette to address the U.S. Congress, stayed at the White House with President Millard Fillmore over New Year’s Eve, and even had a handful of small towns throughout the United States named after him. In sum, he was an icon because of the movement he represented. “Louis Kossuth is one of the great men of the day. Like Washington, Napoleon, Charles the Twelfth, Frederick the Great, and Alexander, he fills a brilliant page in history… [and] occupies the heart of the republican world.”[5] In 1990, just before the end of the Cold War, the American Hungarian Federation erected a bust of Kossuth in the U.S. Capitol. The inscription: “Father of Hungarian Democracy, Hungarian Statesman, Freedom Fighter, 1848–1849.”

[1] New York Times, December 8, 1851.

[2] The Liberator, Boston, January 2, 1852. “Recreancy of Kossuth”

[3] See: Jonathan Israel, The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848 (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017); Mike Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolutions (London: Hachette Digital, 2008).

[4] Daniel Webster, Sketch of the Life of Louis Kossuth, Governor of Hungary (New York: Stringer & Townsend, 1851), 86-91, 29. Chevalier J. G. Hulsemann, Charge d’Affairs at the Austrian Legation, Washington DC, to Daniel Webster, U.S. Secretary of State, Sept. 30, 1850. Webster to Chevalier, Dec. 21, 1850.

[5] The Washington Union, October 16, 1851.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

3 thoughts on “Antebellum Icon: Republicanism vs. Monarchy and Kossuth in America, 1851-1852”