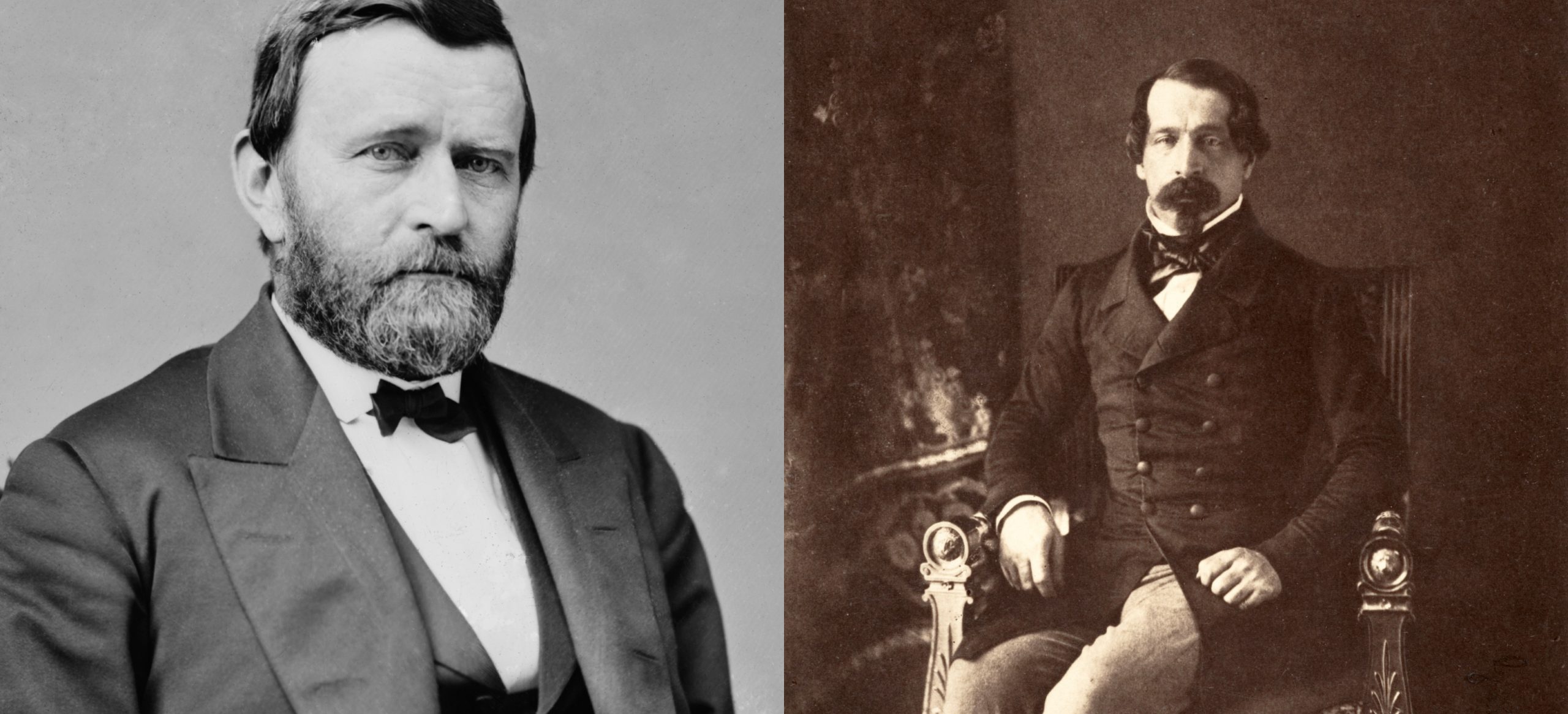

Ulysses S. Grant’s and Napoleon III’s photographic portraits

I never admired the character of the first Napoleon; but I recognize his great genius. His work, too, has left its impress for good on the face of Europe. The third Napoleon could have no claim to having done a good or just act.[1]

—–Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 1885

Grant’s 1885 autobiography is generally remembered as the seminal work of a general praised for helping save the Union during its darkest hour, but insights on the Civil War’s impact on international geopolitics can be gleaned from John Russell Young’s account of Grant’s post-presidential world tour in the late 1870s. Free of the trappings of executive office, Grant toured much of Europe and Asia while enjoying the company of statesmen, kings, and commoners alike.

John Russell Young, and Irish émigré to America and New York journalist who worked for the U.S. State Department, wrote of him that there were…

…few men more willing to converse on subjects on which he is acquainted than General Grant. The charm of his talk is that it is never about anything that he does not know, and what he does know he knows well. He is never vindictive, and never gossips and when referring to men and things in his eventful career seems passionless…[2]

“Enemy of America and liberty”

Although a retrospective Grant offered his views on international aspects of the American Civil War, one figure appearing to elicit passion and vindictiveness not apparent to Young was the former president’s dislike of Napoleon III (1808-1873). In contrast, Grant was taken with the future French Prime Minister Léon Gambetta and most impressed with the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

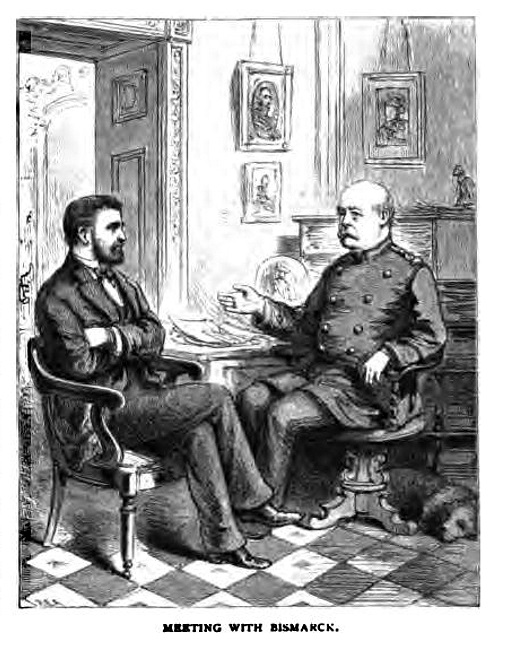

“‘Speaking of the notable men I have met in Europe,’ said General Grant, ‘I regard Bismarck and Gambetta as the greatest. I saw a good deal of Bismarck in Berlin, and later in Gastein, and had long talks with him. He impresses you as a great man.’” As a general, Grant most likely respected Bismarck’s military background and astute realpolitik during a dynamic period in Europe. Another reason it may have been easy to admire him lay in the fact that the Germans were not involved North American geopolitics during the Civil War to the degree of the British and French. The 1864 French installation of Austrian Habsburg and archduke Maximilian I as emperor of Mexico at the height of the U.S. Civil War tested Grant’s normally stoic demeaner. While Grant lamented Maximilian’s “unfortunate and unnecessary execution” in 1867 at the very hands of the insurrectionary group Civil War-era administrations supported, he put the blame on Napoleon III because without French military assistance the installation of the unpopular foreign monarch would not have been possible:

‘I don’t think Napoleon could have rallied France into a war against us in defense of slavery. You see that he could not rally it against Prussia. His empire, never really strong, would have had such a shock that it would most probably have fallen, as fall it did five years later…’ This led to a conversation upon the character of the French emperor and of Napoleonism generally. ‘I have always had,’ said General Grant, ‘an aversion to Napoleon and the whole family. When I was in Denmark the Prince Imperial was there, and some one thought it might be pleasant for me to meet him. I declined, saying I did not want to see him or any of his family. Of course the first emperor was a great genius, but one of the most selfish and cruel men in history. Outside of his military skill I do not see a redeeming trait in his character. He abused France for his own ends, and brought incredible disasters upon his country to gratify his selfish ambition I do not think any genius can excuse a crime like that. The third Napoleon was worse than the first, the especial enemy of America and liberty. Think of the misery he brought upon France by a war which, under the circumstances, no one but a madman would have declared. I never doubted how the war would end, and my sympathies at the outset were entirely with Germany. I had no ill-will to the French people, but to Napoleon.’[3]

Recognition of the Confederacy

While touring India in 1879 Grant was asked about his thoughts on British and French recognition of the Confederacy, which during the height of the Civil War many believed possible. Grant dismissed the notion by saying he “‘never shared the apprehension felt by so many of our leading men,’” and proffered a few reasons as to why. First, he asserted it “‘would not have interfered with Canby, or Meade, or Sherman, who would have kept on marching.’”

Second, Grant concluded it “‘would not have interfered with our money supplies, as we were buying our own loans.’” Third, recognition “‘would not have affected supplies of men, as we did not have more than three per cent, of our army who were not full citizens when the war began. We would have gone on about the same, and ended about the same.’” The general also claimed British recognition would have resulted in a simultaneous war with Canada, which in the end “‘would have meant the withdrawal of England from the American continent. Canada would have become ours. If Sheridan, for instance, with our resources, could not have taken Canada in thirty days he should have been cashiered.’” Mindful of how his frankness might have been interpreted back home, Grant mixed niceties with the military reality as it existed during the great war: “‘I don’t mean this as a reflection upon the patriotism or bravery of the people of Canada, they are as good a people as live, but facts were against them. We could have thrown half a million of men into their country, not militia but men inured to war. They would have covered Canada like a wave.’” Lastly, Grant downplayed the potential impact of a British naval blockade on the United States:

‘Well, I cannot think of anything that would do America more good than a year or two of effective blockade. It would create industries, throw us back upon ourselves, teach us to develop our own resources. We should have to smuggle in our coffee – we could raise our own tea. It would keep our people at home. Hundreds if not thousands of privateers would have preyed upon English commerce, as English-built ships preyed upon ours. The war would have left her carrying trade where our trade was. If England were to blockade our ports, she would succeed in nothing so effectively as in cutting off her own supplies of food. America really depends upon the world for nothing. England might have sent troops to help the South, but she would have to send many more than she did to the Crimea to have made herself felt. Her soldiers would not have been as good as Lee’s, because they lacked training. They would have been simply so many raw levies in Lee’s army. So far as I was concerned I see no end to such an intervention but the destruction of the English power on the American continent. Other nations would have come in. The moment England struck us, she would have been struck by her enemies elsewhere. It would have been a serious matter to have made such a war, so far as English opinion was concerned. For these reasons I never feared the bugbear of intervention. I am glad it did not take place, especially glad for the sake of England. I never desired war with England. I do not want an inch of her territory, nor would I consider her American possessions worth a regiment of men. They are as much ours now as if they were under our flag. I mean that they are carrying out American ideas in religion, education, and civilization. Perhaps I should say we are carrying out English ideas. It is the same thing, for we are the same. But the men who governed England were wise in not taking an active part in our war. It would have been more trouble to us, but destruction to them. We could not have avoided war, and our war would have begun with more than a million of men in the field. That was our aggregate force when the war ended, and it was a match for any army in the world, for any at least that could be assembled on the American continent.’[4]

[1] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, vol. 2 (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885), 547. See: Don H. Doyle (ed.), American Civil Wars: The United States, Latin America, Europe, and the Crisis of the 1860s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2017).

[2] John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant: A Narrative of the Visit of General U.S. Grant, Ex-President of the United States, to Various Countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa, in 1877, 1878, 1879, vol. 2 (New York: Subscription Book Department, 1879), 151.

[3] Ibid. 161, 165-6.

[4] Ibid. 167-170

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.

One thought on “Grant vs. Napoleon III: Reflections on Mexico’s Emperor, the British, and North American Civil War”