I-See-O, also known as Tahbonemah (c. 1849-1927)

In February, 1889, a husky Kiowa came in off the plains to the headquarters of the Indian Territory, presented himself to Lieut. Hugh L. Scott, then a new officer at Fort Sill [Oklahoma], and asked to be enlisted with the scouts. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. The two men conversed in the sign language… During thirty-eight years, Scott and his Indian friend continued to communicate silently, using only their battle-scarred hands – for the redskin never learned to speak English. Silently, gesticulating as they rode, these two warriors of different races hit the frontier trails together.[1]

— Frank Maitland, New York World, 1927

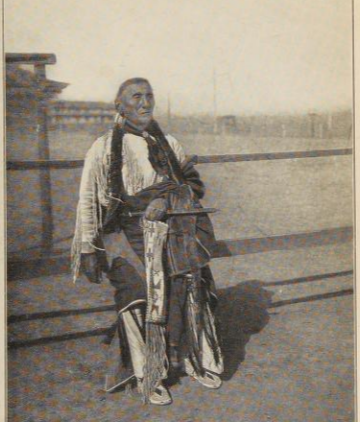

Born to Kiowa parents in Indian Territory in the Oklahoma-Kansas region shortly after the 1848 conclusion of the Mexican-American War, Tahbonemah (Ta-bone-mah), later known as Sergeant I-See-O, would serve the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment as a tracker for nearly four decades until his death.

Scouts from various Tribal Nations, notably the Shoshone, Pawnee, Apache, and Navajo, played essential roles in aiding the American subjugation of the Great Plains and West during the nineteenth-century Indian Wars. The 7th Cavalry, formed at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1866 after the Civil War, played a prominent part in that epoch. In his concise 2003 work, US Army Frontier Scouts, 1840-1921, historian Ron Field writes that “the American frontier scout was vital during the period of westward expansion… Possessing a priceless knowledge of the geography, people and characteristics of the hinterland…” However, like many trackers before him, Tahbonemah – whose legacy would largely be defined by his services as a peacemaker – began his warrior life as an enemy of the U.S. Army.[2]

Warpath to Army Warrior

Following the Civil War, U.S. expansion hastened across the Great Plains and clashes with numerous tribes erupted. In 1867, representatives from a handful of Plains Nations: Kiowa, Apache, Comanche, Southern Arapaho, and Southern Cheyenne, agreed to sit down with General William Tecumseh Sherman and U.S. officials near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, to negotiate an end to hostilities. Some holdouts among the Kiowa resisted, including Tahbonemah, but it became apparent that the traditional ways of warring and long-distance raiding were coming to a close.

In a 1927 article, “Last of the Scouts,” Frank Maitland of the New York World wrote: “Except for his presence at the Treaty of Bentison Lodge, Kansas, in 1867, he was unknown to white men before 1889; he had been continually on the warpath. He was a mature fighter when he offered himself for service with the scouts.” That service, along with his friendship with Lt. Hugh L. Scott of the 7th Cavalry, would last the rest of his life. In his 1928 memoirs, written after the death of his friend, Scott wrote that “I-see-o was a very simple honest Indian, brought up in the old times with the buffalo, having spent a large part of his life on the war-path on the Arkansas [River], in Texas, and in Mexico.” According to Scott, I-See-O may have been motivated to enlist in 1889 to help avoid “a very serious situation… developing which bade fare to bring about a clash with troops” – and Scott wisely resisted calls by whites to forcibly disarm the Indians of the region.[3]

Peacemaker

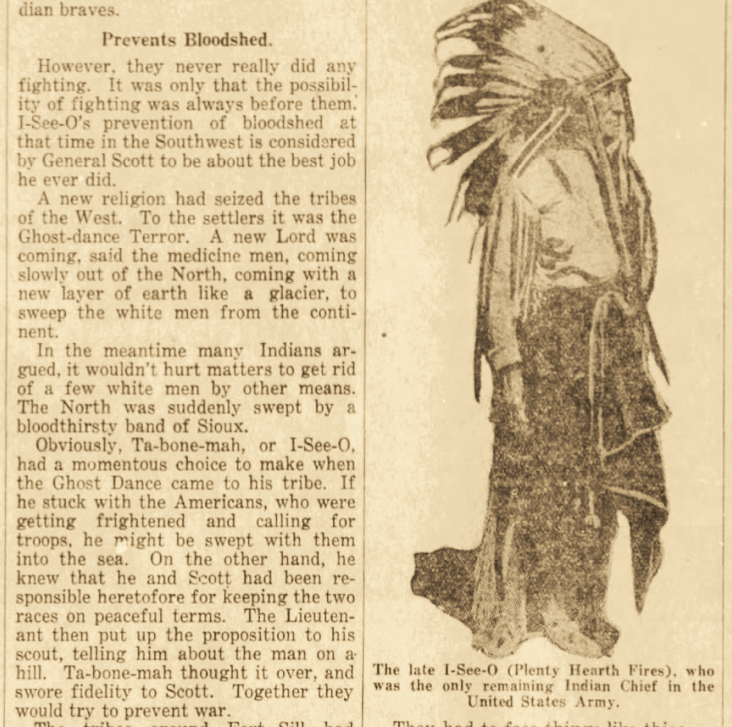

I-See-O is often known for his work with Scott in preventing more bloodshed during the “Ghost Dance” phenomenon that swept the Plains for the two years after he enlisted, but there were many instances where he mitigated potential hostilities between Indians and whites. One such incident occurred in the Indian settlement of Anadarko, near Oklahoma City, where “a white school teacher whipped two Indian children, who ran away in a snowstorm and were frozen to death.”

Soon after, “Indians rose in anger and began pouring into” the settlement, and the Indian agent there requested protection from Fort Sill. Rather than send a contingent of soldiers, Scott pleaded to his commanding officer that he send only I-See-O, another interpreter, and himself. “The scout carried the interpreter all night on his horse through deep snow, and they arrived at Anadarko to find the town in a turmoil.” In the interim, an uncle of one of the children found the teacher and “beat him with a horsewhip” – resulting in the arrest of the uncle – an escalation that “meant war, and Scott knew it.” Then, the three men “argued fiercely with the schoolteacher and the agent, finally obtaining the Indian’s release. But the Kiowas and Comanches were moving in on the schoolhouse, where all the women and children were in uproar over fear.” There is no telling what would have happened had the peacemakers of Fort Sill not arrived.[4]

Reenlistment and Legacy

Shortly before the outbreak of World War One, and after the closing of the frontier, I-See-O left the U.S. Army to live in Oklahoma with his family. By that time his old friend Hugh L. Scott had become a general, and requested that the government financially assist the old and destitute tracker for his service to the United States by allowing him to receive pay as an active soldier – a request that was granted.

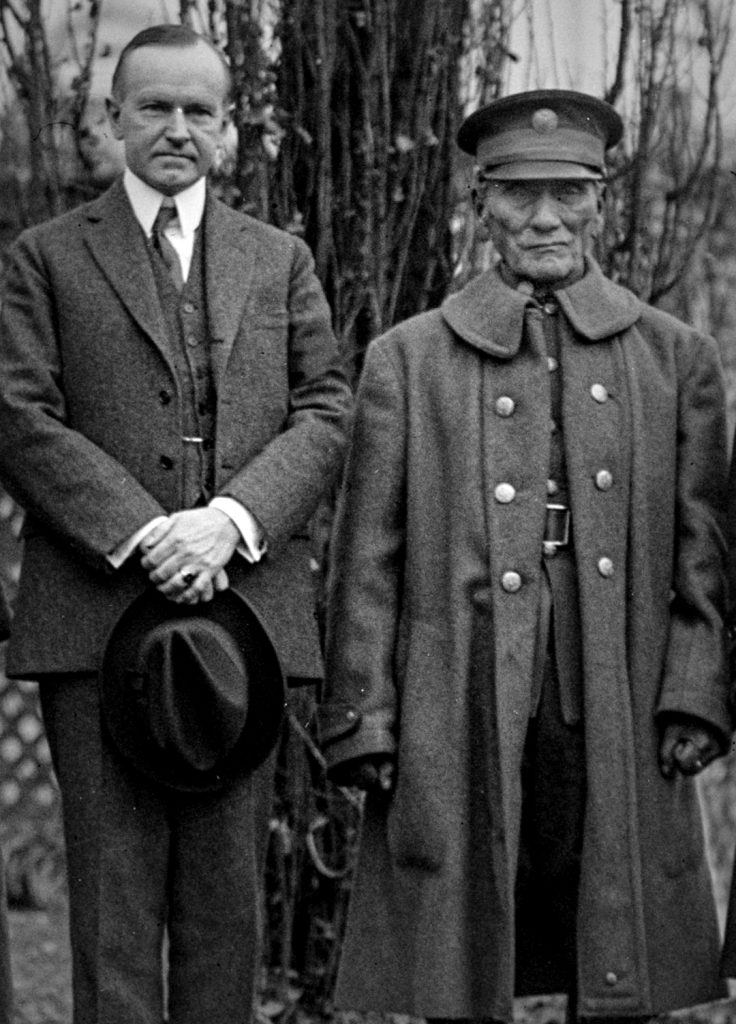

His reactivated status apparently making him “the oldest enlisted soldier in the United States – and so far as known, in the entire world…” By this time, I-See-O had become somewhat of a legend, and even met General John “Black Jack” Pershing when he visited Fort Sill after WWI. According to the Kiowa County Review, “After the World War, General John J. Pershing… paid a compliment to the old Indian scout and asked that special courtesies be shown him the remainder of his life. The request has been fulfilled.” When he died in 1927, after having met a U.S. President, Sergeant I-See-O may not only have been the last Indian tracker in the U.S. Army, but its oldest active-duty soldier.[5]

[1] Frank Maitland, “Last of the Scouts” The Antlers American, Antlers, Oklahoma, July 14, 1927. (via New York World).

[2] Ron Field, US Army Frontier Scouts, 1840-1921 (Oxford: Osprey, 2003), 3. See: Thomas W. Dunlay, Wolves for the blue soldiers: Indian scouts and auxiliaries with the United States Army, 1860-90 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982); James B. Klokner, The Officer Corps of Custer’s Seventh Cavalry, 1866-1876 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2007).

[3] Maitland, “Last of the Scouts” The Antlers American, Antlers, OK, July 14, 1927. (via New York World); Hugh Lenox Scott, Some Memoirs of a Soldier (New York: The Century Company, 1928), 147.

[4] Maitland, “Last of the Scouts”

[5] “Oldest Soldier is Hobart Visitor” The Kiowa County Review, Hobart (OK), October 22, 1926.