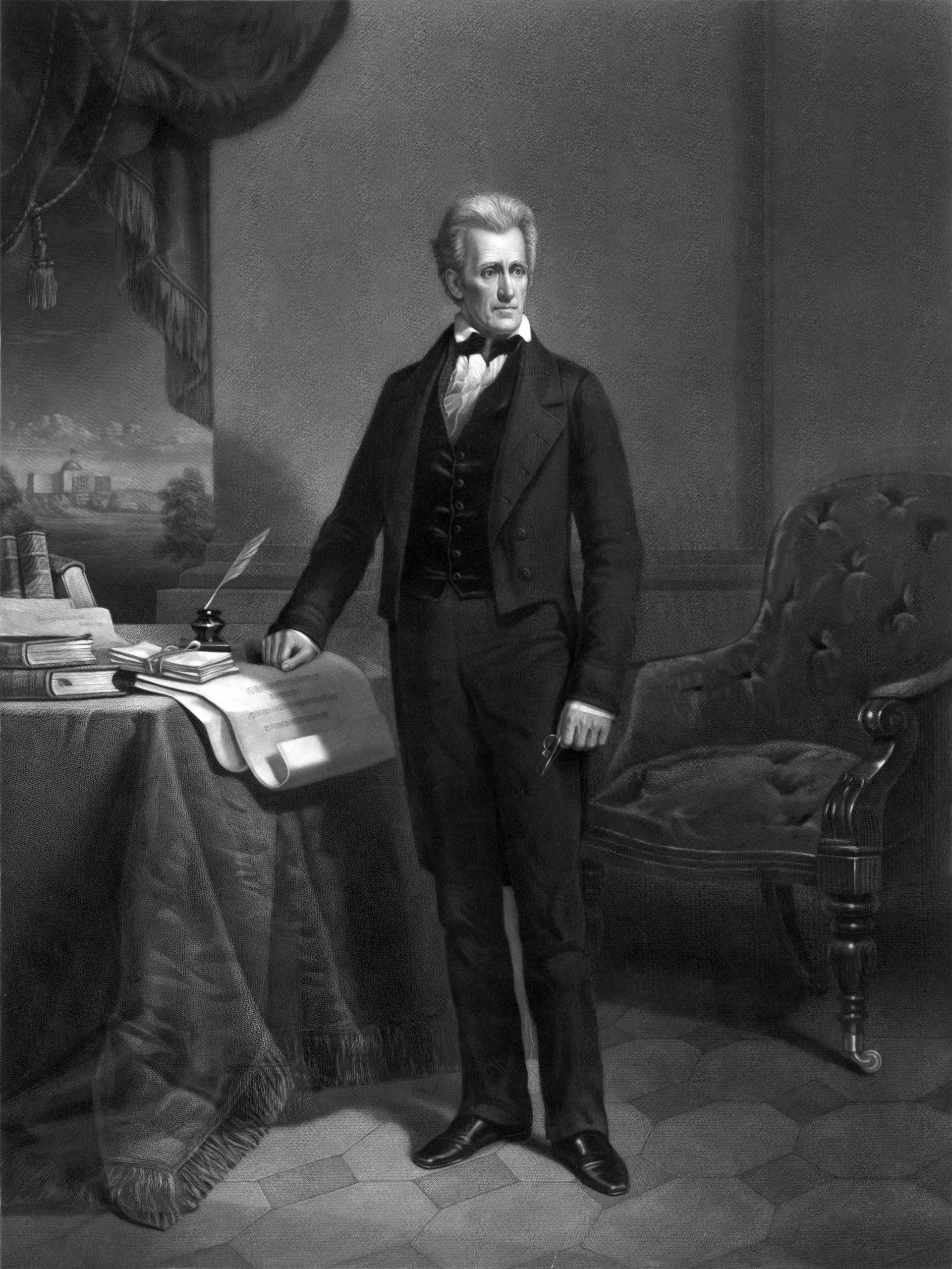

President Andrew Jackson (1829-1837)

British depredations upon U.S. merchant vessels and impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy contributed to the start of the War of 1812, but the U.S. also had issues with Great Britain’s rival France. In 1806, three years after the Napoleonic Wars began, Napoleon decreed that property belonging to U.S. ships could be seized despite U.S. neutrality. As a result, U.S. vessels and crews were subject to capture by the French Navy until the emperor’s abdication in 1815.

Writing in the early twentieth century, the historian Richard McLemore noted that when John Quincy Adams became president in 1824 Secretary of State Henry Clay “thought that Adams should recommend to Congress the ‘issuing of letters of marque of reprisals’” – which were maritime licenses to legally confiscate (pirate) property from another state’s vessels. The proposal was tabled, and the issue abated somewhat until Andrew Jackson was elected President in 1828.[1]

The 1829 Congressional Message

In his first annual message to Congress Jackson brought up the “injurious delays” over the spoliation issue with the nation’s “ancient ally,” and noted that “claims of our citizens for depredations upon their property, long since committed under the authority, and in many instances by the express direction, of the then existing government of France, remain unsatisfied…” Jackson’s willingness to publicly accuse the French was a novel and controversial way of conducting foreign affairs. “Our minister has been instructed to press these demands on the French government with all the earnestness which is called for by their importance and irrefutable justice…”[2]

With increased attention drawn to the matter, in 1831 William C. Rives, Jackson’s minister in Paris, was able to conclude a reparations treaty for the repayment of $5,000,000. Despite the treaty’s popularity among U.S. politicians, when the first payment was due in 1833, the French Chamber of Deputies refused to pay.[3]

Jackson’s 1834 State of the Union Address

Franco-American relations worsened when Jackson was reelected in 1832 in a landslide victory. With the increase in political capital an emboldened Jackson asserted executive power in dealing with the French. In his State of the Union address in 1834 Jackson noted that it was his “unpleasant duty to inform” Congress of deteriorating U.S.-French relations and restated the American case:

The history of the accumulated and unprovoked aggressions upon our commerce committed by… France between the years 1800 and 1817 has been rendered too painfully familiar to Americans to make its repetition either necessary or desirable. …for many years… the French Government by whom the justice and legality of the claims of our citizens to indemnity were not to a very considerable extent admitted, and yet near a quarter of a century has been wasted in ineffectual negotiations to secure it.[4]

In addition to reiterating his demand for reparations, Jackson warned if the French failed to pay he – like Henry Clay previously – would “recommend that a law be passed authorizing reprisals upon French property…” The president also lamented that a possible “Collision with France is… to be regretted” and that Congress take appropriate action “to protect the rights and maintain the honor of the country.”[5]

U.S. War with France?

When the French learned of Jackson’s congressional address they recalled their minister from Washington – which in turn resulted in the U.S. minister in Paris departing France. Jackson’s domestic political opponents were equally incensed. However, what his detractors did not understand was that his brinksmanship approach to the longstanding French indemnity brought the issue into the forefront and caused an otherwise ambivalent international audience to address it. At first the French were insulted, but when Jackson refused to back down people on both side of the Atlantic began to believe that war was imminent. The Pittsburgh Gazette reported on the British reaction from Liverpool:

The state of our connection with France is very peculiar at this crisis; …should America force France into a contest – which [King] Louis Phillippe is most anxious to avoid – the chances are pretty even, that the English Foreign Secretary (the Duke of Wellington) would eagerly seize the opportunity of aiding Russia, Austria, or Prussia, or all these powers, in picking a quarrel with la belle France! Louis Phillippe knows this, and therefore he will take care to avoid the extremity of an appeal to arms.[6]

The question, then, was not what the Americans would do, but what the numerous rivals of France would do in the event of war with the United States. In other words, it was a calculated but relatively prudent gamble by Jackson. Win or lose, the Americans would keep their honor and repair commercial relations potentially affected by war. The French, on the other hand, were not willing to bet what their various European opponents would do. Ultimately, the result of Jackson’s insistence was French repayment of the spoliations claims in 1836.

[1] Richard A. McLemore, “The French Spoliation Claims, 1816-1836: A Study in Jacksonian Diplomacy.” Tennessee Historical Magazine 2, no. 4 (1932): 234-237.

[2] The Addresses and Messages of the Presidents of the United States (New York: McLean & Taylor, 1839), 340. President Jackson, First Annual Message to Congress, December 8, 1829.

[3] McLemore, “The French Spoliation Claims, 1816-1836,” 240-241.

[4] Congressional Globe, Library of Congress (LOC), 23rd Congress, 2nd Session, Washington DC, December 2, 1834, 2-3.

[5] Ibid. 4

[6] Pittsburgh Gazette, February 24, 1835.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson has been living and working in Korea since 2008. His doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, covered Euro-American military and legal history, and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department for Human Creativity at Hoseo University in Asan – where he lives with his wife and son. His hobbies include chess, painting, hiking, and bonsai.

2 thoughts on “President Jackson Confronts France: The Spoliations Showdown, 1834-1836”