William of Rubruck and his traveling companion (upper portion) with Louis IX of France. Illuminated initial from Friar William of Rubruck’s Itinerarium, early 14th century

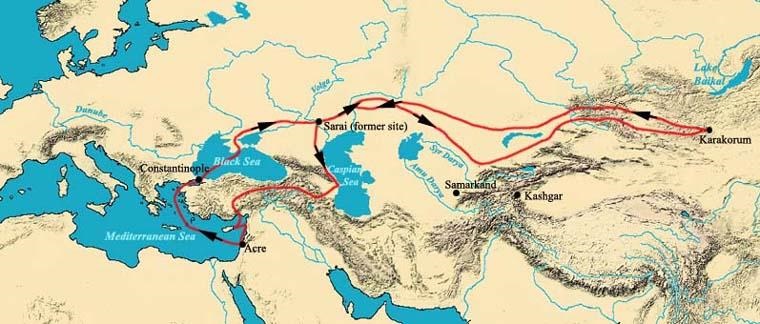

After a Levantian crusade in 1253, Flemish Franciscan monk William of Rubruck ventured further east on the Silk Road by way of Constantinople and the Black Sea in search of the fabled Mongolian capital of Karakorum.

The monk thereinto wrote the most detailed account of that vast empire, and was particularly interested in the Nestorian Christians – a small but influential faction within the “court of the Great Khan Möngke.” In a 1900 English translation of the 9,000-kilometer journey, William W. Rockhill believed Rubruck’s chronicle across the heart of the Eurasian continent was “a work which should rank as high in the literature of travel as that of Marco Polo, his better-known successor in the field of Asiatic exploration…” Indeed, little was known by Europeans about the world beyond the Urals, and it was a journey fraught with both mystery and danger made possible by Mongolian cessation of hostilities in the west.

In 1243, Pope Innocent IV proclaimed a crusade to liberate the Hungarians “‘against the envoys of Satan, the ministers of the Tartarus,’ and promising the same indulgences as for a crusade to the Holy Land.” It was believed by Innocent and others among the “Mendicant Orders of St. Dominic and St. Francis” that alliances with Eastern Christians might leverage the power of the Tartars who conquered Hungary under the auspices of Batu Khan – founder of the vassal khanate the Golden Horde and grandson of Genghis Khan:

He organized missions, not only among the various heretical sects of Europe and Asia, and the pagan tribes of northeast Europe, but also to the Mongols; in the hope, as he says in a letter to “the King and the Tartar people,” of “averting their onslaughts on Christendom through fear of Divine wrath,” and to preach to them Christianity; as well as with the ulterior purpose of finding out through the missionaries exactly the plans of the Mongols as regarded Europe. The Pope must have been encouraged to believe that his representations might have some effect on the Mongol Sovereign by the prevailing belief in the existence, somewhere in the far East, of the Nestorian Christian realm of Prester John; and probably by the more recent information given him by a Russian bishop named Peter, who had fled before the invaders to Lyons, that “the Mongols worshipped one God, and were not without some religious beliefs.”[1]

The Nestorian Christians

In her 2019 article, “Nestorian Christians in Frontier History,” Borbála Obrusánszky of Karoli Gaspar University, Hungary, points out that Nestorian Christianity in Inner Asia traced its roots from Upper Mesopotamia in the fifty century and subsequently spread to small kingdoms as far as the Junggar Basin (present-day China) before being conquered by Genghis Khan in the early thirteenth century. Obrusánszky asserts Christian missions among the Kereit and Naiman kingdoms “enjoyed considerable freedom” from Mongolian authorities after being conquered:

The Nestorins arrived among the Mongolian tribes from at least two directions: the first was the so-called “Yellow Route”, which led through the Da Qin Mountain to the Gobi; the second was the Mongolian Silk Road, which led through the Altay Mountains and reached the western part of present-day Mongolia. Before the 13th century there was no united khanate in the territory of the former Mongolian Empire, but small khans ruled over territories. Some of them the Nestorians successfully converted to their faith.[2]

Rubruck’s Arrival, Return, and Realization

After more than three months of traveling west of the Volga River basin on horseback, Rubruck and his small group arrived at the fabled city of Karakorum mid-winter. Sometime in early January of 1254 they were given an audience with the “Mangu Chan” – otherwise known as the Great Khan:

I saw the monk with the priests coming back from the court bearing his cross, and the priests had a censer and the Gospels. Now on that same day Mangu Chan had had a feast, and it is his custom on such days as his diviners tell him are holy, or the Nestorian priests say for some reason are sacred, for him to hold court, and on such days first come the Christian priests with their apparel, and they pray for him and bless his cup. When they have left, the Saracen priests come and do likewise. After them come the priests of idols, doing the same thing. The monk told me that (Mangu) believed only in the Christians, but he wanted all to pray for him. But he lied, for he believes in none, as you shall learn hereafter, and they all follow his court as flies do honey, and he gives to all, and they all believe that they are his favourites, and they all prophesy blessings to him.[3]

Rubruck stayed in the east until summer. On their year-long journey home they passed through present-day Azerbaijan before reaching the Crusader state County of Tripoli – in modern-day Lebanon and Syria. The County of Tripoli would be the last crusader state in the Holy Land, and although favoring an alliance with the Mongols, eventually succumbed to the Mamluks in 1289. For the most part, in the period following the Crusades adherents to the ancient eastern sects and Nestorians of the Middle East and Central Asia dwindled amid a changing world, fracturing and dissolution of the once great Mongolian empire, and rise of competing Islamic states – particularly the Ottomans.

Although Constantinople remained the Christian capital of the Eastern Roman Empire until it was finally conquered in 1453, lands outside its storied walls became more dangerous to travelers and obstinate monks such as Rubruck. The Flemish friar who miraculously managed to return home to tell his tale wrote that during the Crusades, “In times past valiant men passed through these countries, and succeeded, though they had most powerful adversaries, whom God has since removed from the earth.” Ultimately, however, Rubruck concluded in diplomatic language directed at the new Pope that the world was too big, too wide, and too diverse for the ruler of the Catholic Church, or the kings of Europe, to conquer:

Nor should we (if we followed this road) be exposed to the dangers of the sea or to the mercies of the sailor men, and the price which would have to be given for a fleet would be enough for the expenses of the (whole) land journey. I state it with confidence, that if your peasants – I speak not of the princes and noblemen – would but travel like the Tartar princes, and be content with like provisions, they would conquer the whole world. It seems to me inexpedient to send another friar to the Tartars, as I went, or as the preaching friars go; but if the Lord Pope, who is the head of all Christians, wishes to send with proper state a bishop, and reply to the foolishness they have already written three times to the Franks (once to Pope Innocent the Fourth of blessed memory, and twice to you… who deceived you, and now by me), he would be able to tell them whatever he pleased, and also make them reply in writing. They listen to whatever an ambassador has to say, and always ask if he has more to say; but he must have a good interpreter – nay, several interpreters… [4]

[1] William Woodville Rockhill, ed., The Journey of William Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253-1255 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1900), x, xxi.

[2] Borbála Obrusánszky, “Nestorian Christians in Frontier History” Journal of Frontier Studies, no. 3 (September 2019), 177-8. See: Timothy May, “Converting the Khan: Christian Missionaries and the Mongol Empire,” World History Connected (June 2015)

[3] Rockhill, ed., The Journey of William Rubruck, 182.

[4] Ibid. 281-2.