U.S. Army occupation of Mexico City in 1847.

Isolated from every other branch of the army, barred by intervening deserts from all communication with the government, thrown entirely upon its own resources, compelled to draw supplies from a hostile country, and in the absence of instructions or succors, Colonel Doniphan’s command was left to cut its way through the country of a subtle and treacherous enemy. Destitute of clothing, and the means of procuring it – not having received a dime since the day of enlistment, and none then, save forty-two dollars commutation for clothing – the men almost grew as did Nebuchadnezzar, being indeed rough samples of Rocky Mountain life. Their long-grown beards flowed in the wind similar to those of the rude Cossacks of northern Europe, while their garments were worn to shreds, bivouacking on the rocks and sands of Mexico. – Their disheveled hair, their long-grown whiskers, their buck-skin apparel, their stern and uncouth appearance, their determined and resolved looks, and their careless and nonchalant air, attracted the gaze, and won the admiration of all people. Though they were somewhat undisciplined, yet they were hardy, unshrinking, resolute, independent, chivalrous, honorable and intelligent men, such as, indeed, “would not flatter Neptune for his trident, nor Jove for his power to thunder.”[1]

— John T. Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition, 1848

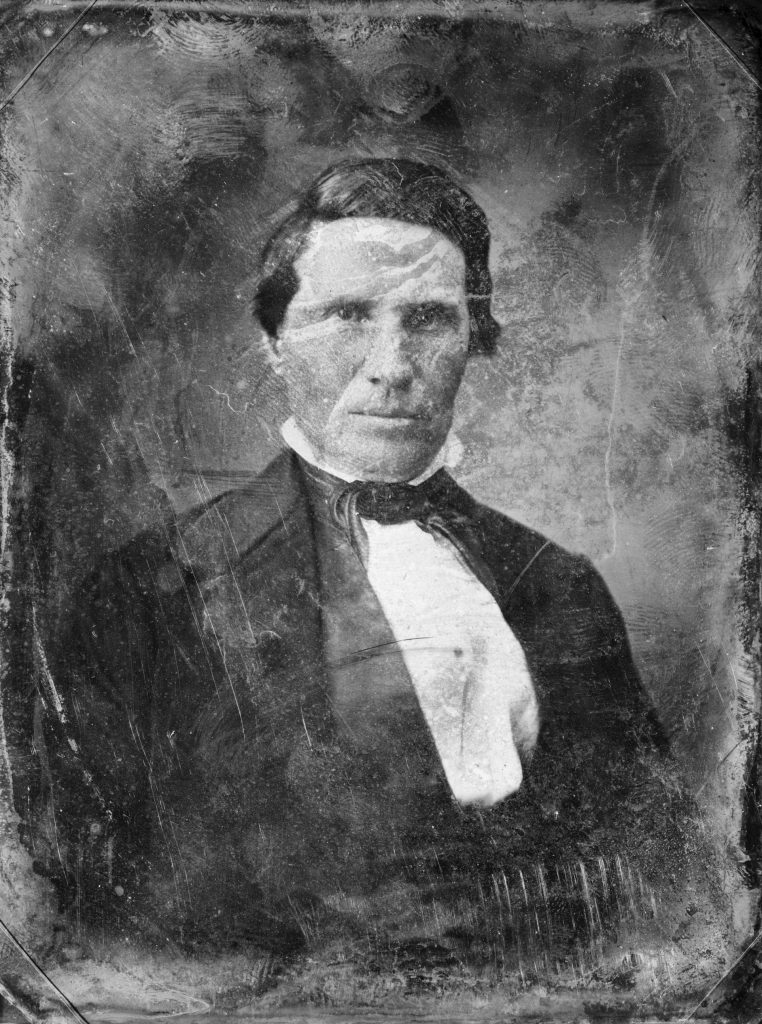

Alexander William Doniphan is well known among Mormons for his saving Joseph Smith from certain death in the 1838 Mormon War, but his Mexican-American War expedition covering swaths of the Southwest was hailed at the time as a military achievement. In the fall of 1846 Doniphan, an attorney-turned-colonel in the expansionist war, led the 1st Regiment of Mounted Missouri Volunteers out of occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico, into hostile lands of the Navajo and northern Mexican states including Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo Leon.

An 1848 post-war account of the expedition was chronicled by John Taylor Hughes, a private who served under Doniphan who went on to become a Brigadier General for the Confederate Army during the Civil War. “For, what can be more wonderful than the march,” Hughes wrote, “of a single regiment of undisciplined troops, through five populous States of the Mexican Republic – almost annihilating a powerful army – and finally returning home, after a march of near six thousand miles, graced with the trophies of victory?” Like others familiar with the expedition, Hughes believed Doniphan did not receive the recognition he so rightly deserved:

Mexico has recently been the theatre of many thrilling events. The presses of the country are teeming with books, written on Mexico, the Mexican war, and Mexican manners and customs. Descriptions of camps, marches, battles, capitulations, and victories, have almost sated the public mind. But these have all, or nearly all, had reference to the central or southern wings of our army. Little has been said, or written, in regard to the “Army of the West.”[2]

Indios Barbarous and Borderlands

One aspect often overlooked in war narratives critical of U.S. annexation of Texas and conquest of the borderlands extending to the Pacific was the near lawless nature of several tribes that had long occupied the region. Among these, the Navajo, Apache, and Comanches were the most formidable and their hostility served as a bulwark to effective Spanish and subsequent Mexican colonization of the region. It was for this reason whites from the United States were initially invited to settle in Texas. Historian David B. Adams notes that in the years after the war between 1848 and 1870, “Nuevo Leon suffered 809 recorded incursions by the indios barbarous” – the term used by Mexicans to describe the Native Americans. General Stephen W. Kearny, commander of U.S. forces who seized New Mexico, initially invited the Navajo to Santa Fe “for the purpose of holding a council, and making a peace between them and the inhabitants of New Mexico… under the protection of the United States” but the Navajo declined, “and instead thereof continue killing the people and committing depredations…” The result was that Kearny sent Doniphan into the heart of Navajo territory to attempt to subdue the tribe. Hughes also recalled the condition of the regiment prior to their departure in October of 1846:

Four months’ pay was now due the soldiers, and many of them would soon be destitute of comfortable clothing, yet Col. Doniphan had neither a military chest, nor a paymaster, nor a dollar of government funds to silence the just complaints, or satisfy the reasonable wants, of his men. They looked upon it as a hardship, and with reason, that they were ordered against the Indians, without pay, and with little else than their summer clothing to protect them from the cold, in a country where they would be compelled to climb over the tallest mountains, and often encamp in the midst of snow, and ice, and rocks, and where it was impossible to procure either wood for fire, water to drink, or forage for horses and mules.[3]

Along the long march the regiment learned much about the wild geography of the region and the people that lived there in relative isolation. They learned that Pueblo Indians were often victims of Navajo depredations and that various tribes had longstanding grievances against each other – most of which preceded the American arrival to the region. They learned to post well-armed guards when camping and to never let small groups venture off too far without an armed escort. In their free time they held “contests of wrestling, running and jumping; also in jokes, songs and speaking; or else in smoking, lounging, sleeping, cardplaying or reading, as the humor might prompt them.”

On Christmas day near Las Cruces, New Mexico, while en route to Chihuahua, Doniphan’s regiment confronted a larger force of Mexicans who charged them. The Americans held their ground. Hughes wrote the enemy numbered around 1,300 men with about “five hundred and fourteen regular dragoons” from Zacatecas and Veracruz. “They exhibited a most gallant and imposing appearance; for the dragoons were dressed in a uniform of blue pantaloons, green coats trimmed with scarlet, and tall caps plated in front with brass, on the tops of which fantastically waved plumes of horsehair, or buffalo’s tail. Their bright lances and swords glittered in the sheen of the sun.” Two days later, Doniphan seized El Paso, Texas, which at the time was part of the state of Chihuahua.[4]

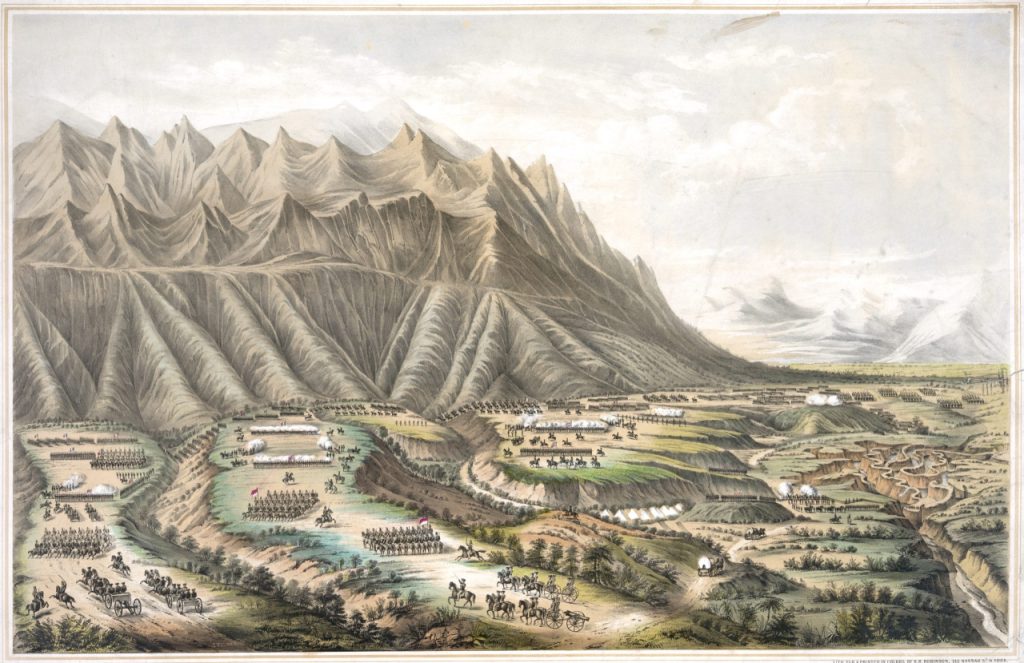

Battle of the Sacramento River, Chihuahua, and Return Home

On February 28, 1847, north of the City of Chihuahua, Doniphan’s forces, which numbered around 900 men, encountered entrenched positions defending the city and defeated a Mexican army of more than 4,000 soldiers. The effective use of howitzers in combination with cavalry was essential to victory. “It is abundantly shown,” Doniphan reported, “in the charge made… with the section of howitzers, that they can be used in any charge of cavalry with great effect.” Hughes commented that the Mexicans were “So certain of victory were the Mexicans, that they had prepared strings and handcuffs in which they meant to drive us, prisoners, to the city of Mexico, as they did the Texans in 1841.”[5]

On March 18 the Americans learned of a major victory by General Zachary Taylor against General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at Buena Vista February 22 and 23. Doniphan held the Chihuahua City for forty-nine days before departing to Saltillo to join the main force.

Following the regiment were a few “fair Mexican girls, who had conceived an unconquerable attachment for some favorite paramour of the Anglo-saxon race, with ‘blue eyes and fair hair,’ dressed in the habit of Mexican youths… They accompanied their lovers on the march to Saltillo, and bivouacked with them on the deserts.” On June 10, after a long journey to the mouth of the Rio Grande, the men bordered two steamers heading for New Orleans, “and under a favoring gale arrived safely… on the 15th, having, in twelve months, performed a grand detour through the Mexican Republic, of near four thousand miles, by land and water.” The group were splendidly received in the Crecent City and from there traveled upstream to their homes in Missouri. Hughes wrote:

This most extraordinary march, conducted by Col. Doniphan, the Xenophon of the age, with great good fortune, meets not with a parallel in the annals of the world. We had now been in the service twelve months, had traversed the plains and solitudes of the west, had waded through the snows in the mountains of New Mexico, had traveled over the great deserts of Chihuahua, Durango, Coahuila, Nueva Leon, and Tamaulipas, half-naked, and but poorly supplied with provisions, and were weary of camp service, and packing up baggage. Therefore we were anxious to return to our homes and our families. […] As they passed up the Mississippi, the streaming of flags from the tops of the houses, and the waving of white handkerchiefs by the ladies, as a token of approval, from the windows and balconies of the stately mansions which everywhere beautify the green banks of the “Inland Sea,” announced to them that their return was hailed with universal joy ; that their arduous services were duly appreciated; and that Louisianians are not only generous and brave, but nobly patriotic. Such a reception was worth the toil of a hundred battlefields.[6]

[1] John Taylor Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition (Cincinnati: J.A. & U.P. James, 1848), 378.

[2] Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition, iii, iv. See: William Elsey Connelley, Doniphan’s expedition and the conquest of New Mexico and California (Topeka, Kansas: 1907).

[3] David B. Adams, “Embattled Borderland: Northern Nuevo León and the Indios Bárbaros, 1686-1870,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 95, no. 2 (1991), 220; Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition, 143-6.

[4] Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition, 151-7, 261.

[5] Ibid. 317, 305.

[6] Ibid. 335, 351-2, 374-8.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.