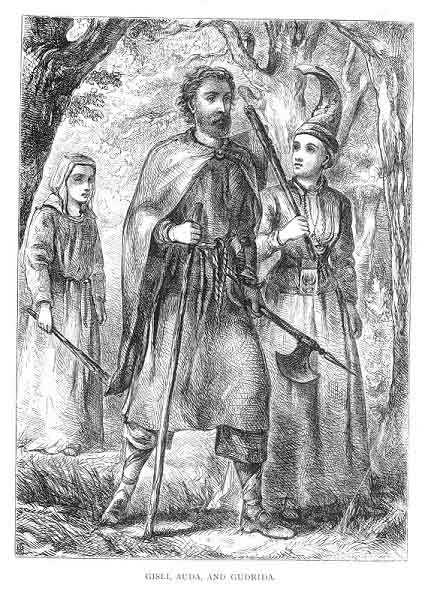

Gisli slips through Thorgrim’s brother fingers.

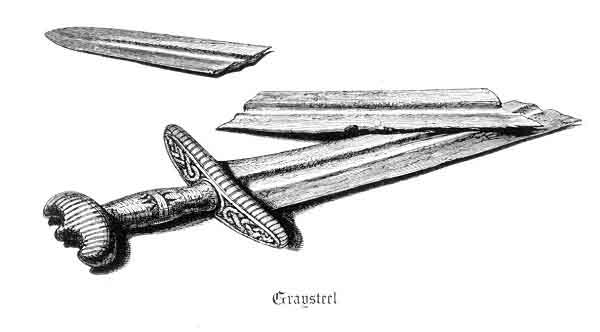

An illustration from Gísla saga, 1866

The Saga of Gisli Sursson, or Gisli the Outlaw – believed to have been written sometime in the thirteenth century – is an exceptional window into the Viking world during a period of profound and rapid change. Imbedded within the story centering around one family’s curse and relocation to Iceland in the 950s during an era of conversion from paganism to Christianity is a drama of revenge and honor whose main protagonist Gisli seemingly does everything proper and within the law yet becomes a tragic victim of forces beyond his control. Writing in 2017, Jon Gunnar Jørgensen, professor of Norse philology at the University of Oslo, notes Gisli the Outlaw “was written at a time when the Icelandic Commonwealth was in decline and the Church had long since become powerful and well organised.”

Moreover, accompanying the thematic richness of the text are numerous passages enlightening our understanding of practices held by Norsemen. Examples of this richness include the requirement of obtaining a prima signatio (sign of the cross) to conduct trade with Christians, the socio-hierarchical complexities of honor killing, and descriptions of the traditional burial practice known as the “howe” – or boat burial.[1]

Prima Signatio

As Christianity spread further into the heart of the Viking world heathen merchants who desired to conduct business with their religious rivals were forced to receive what was known as the prima signatio (sign of the cross) as a precondition – as it was forbidden for Christians to trade with pagans. This also served as an incentive to convert. In his 1866 translation of The Story of Gisli the Outlaw, George Webb Dasent commented on the ritual’s practicality, noting “Christians of England and the West would not deal at all with heathens, or felt easier in dealing with those who had at least received the first initiation into Christianity, the primsigning, or marking with the cross – a sort of baptism, as distinct from christening…” Dasent noted how Gisli and his friend Vestein, “who were not such stubborn heathens as Hallstein or Thorgrim, allowed themselves to be so marked for the sake of doing a good trade.” The saga chronicles how, around the year 960, a storm appearing at sea one night near Hordaland, Norway, caused Gisli and Vestein to make a journey to Denmark:

Their ship was dashed to pieces, but they saved their goods and crew. There was a man off the coast called Beard-Bjalf. He owned a ship, and was on his way to Denmark. So Gisli and Vestein dealt with him for half the ship. He heard they were brave fellows, and gave them half the ship, and they repaid him at once by giving him more than half her worth in goods. So they held on their course for Denmark to that mart called Viborg. They stayed there that winter with a man called Sigrhadd. There they were all three in good fellowship – Gisli, Vestein, and Bjalf. They were great friends, and many gifts passed between them.[2]

Honor Killing

In the saga, Gisli murders a man named Bard, who his father denied as a suitor to his sister, and is forced with his family to flee from Norway to Iceland – the preferred sanctuary for those out of favor with the ruling class in Norway. After arriving, two of Gisli’s sisters get married and thus two brothers-in-law, Thorkel and Thorgrim, are added to the family. Gisli and Thorkel run the same farm, but there is considerable intrigue among the women and men. Gisli also marries Vestein’s sister Auda, and thus his friend becomes his brother-in-law. Gisli tries to maintain unity among the men, but a division ensues and Thorkel and Thorgrim form an alliance against him and Vestein.

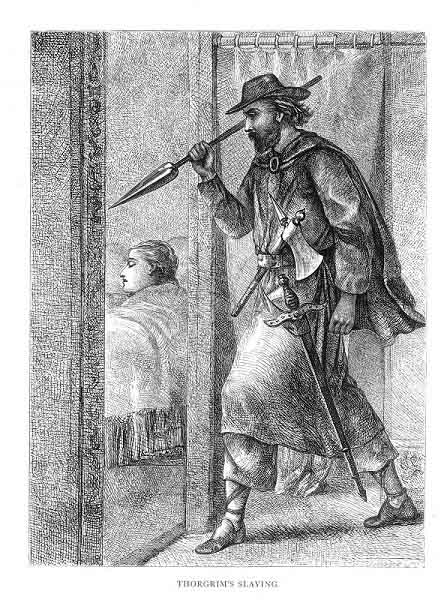

One night, while Vestein is visiting Gisli, a violent storm appears and Gisli leaves to ensure the haystacks do not wash away. Vestein stays behind in the presence of a thrall named Thord the Hareheart. In the early morning Vestein is murdered in his bed with a spear:

Meanwhile Auda awakes, and sees what work was being done. Now Thord the Hareheart comes up, and she told him to pluck the weapon out of the wound, for in those days it was a settled thing that the man was bound to avenge the slain who took the weapon out of the wound, and it was called secret slaying, but not murder, if, when the deed was done, the weapon were left behind. But Thord was so afraid of the dead that he did not so much as dare to come nigh the spot. Then Gisli came in, and spoke to the thrall, and bade him let it alone; and then Gisli went up and took the spear away, and cast it, all bloody as it was, into a chest, and let no man see it. After that he sat down on the bedside, and laid out the body as was the wont; and Gisli thought he had suffered a great loss, and many others with him.[3]

Gisli believes Thorkel and Thorgrim were guilty of the murder, avenges Vestein’s death by killing Thorgrim, and is forced to hide for many years until he too is killed. Jørgensen describes the complicated nature of the murder: “It is also possible that Gisli makes Thorgrim the target of revenge in order to protect his brother [Thorkel] from the later vengeance of Vestein’s sons. If so, this strategy was as unsuccessful as his attempt at foster-brotherhood, because after Gisli had lived as an outlaw for several years, Thorkel falls victim to revenge nonetheless.”[4]

Howe Burial and Hellshoon

In the introduction of his Gisli the Outlaw, Dasent asserted that in “no other Saga do we find the rites of burial in a ‘howe’ or barrow so well described.” In fact, Gisli the Outlaw describes two burials using howes whose occupants were fitted with the mysterious hellshoon (Hell Shoes), and one description in the text indicates their purpose: “And when they had heaped up the howe, and were going to lay the [Vestein’s] body in it, Thorgrim the priest goes up to Gisli, and says, ‘Tis the custom, brother-in-law, to bind the hellshoe on men, so that they may walk on them to Valhalla, and I will now do that by Vestein.’” As noted, Thorgirm presided over the funeral but obviously Gisli had intended to murder Thorgrim after Vestein’s funeral. Dasent described the burials:

Thorgrim the Priest is laid in his boat or ship, and then the howe or cairn is heaped over him. Vestein, the daring sailor, we may be sure, was buried in his ship too; both had the hellshoes fitted to their feet, on which in heathen times the dead were fancied to walk to Valhalla, and both had their ships steadied and kept upright in the howe by great stones. Though Thorgrim only mentions the hellshoon when he binds them on Vestein, and Gisli the stone when Thorgrim’s ship is steadied, it is certain that the burial rites were alike in both cases—that Vestein’s ship was steadied like Thorgrim’s, and that the hellshoon were bound on Thorgrim’s feet, just as he had bound them on Vestein. But both these customs are remembered alone in our Saga.[5]

Gisli’s Epic Last Stand

Thus Gisli’s family the Soursops arrived in Iceland around 952. Thorbjorn, Gisli’s father, passes away soon afterwards. The marriages take place in the early 960s, Vestein is murdered a couple years later, and Thorgrim is laid in his howe in October of 963.

Thorkel is murdered by Vestein’s sons to avenge their father sometime around 972, and Gisli himself is slain sometime around 978, after living as an outlaw on the island of Iceland after fourteen years. He was a wanted, honorable, and dangerous man. With a price on his head and a fate he could not avoid, the scene of his death was anything but quiet. It took fourteen men under a man named Eyjolf to slay the outlaw.

[1] Jon Gunnar Jørgensen, “Code of honour under debate in two Icelandic sagas” Literature and Honour 18 (Dec. 2017), 37. See: Taylor Culbert, “The Construction of the ‘Gísli Saga’”, Scandinavian Studies 31, no. 4 (1959): 151–65; Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, “Inside Outlawry in ‘Grettis Saga Ásmundarsonar’ and ‘Gísla Saga Súrssonar’: Landscape in the Outlaw Sagas,” Scandinavian Studies 82, no. 4 (2010): 365–88.

[2] George Webb Dasent, The Story of Gisli the Outlaw (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1866), xxvii-xxviii, 27; Jørgensen, “Code of honour under debate in two Icelandic sagas” 40.

[3] Dasent, The Story of Gisli the Outlaw,42-43.

[4] Jørgensen, “Code of honour under debate in two Icelandic sagas”, 45.

[5] Dasent, The Story of Gisli the Outlaw, 44, xxiv-xxv.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.