Buda, 1541

If we are willing to make war on the Turks, let us begin here where they are most iniquitous. If we are right in hanging thieves and beheading robbers, why should we leave Avarice of Rome unpunished?[1]

Martin Luther

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 Ottoman domination of southeastern Europe proceeded rapidly – causing a political and religious crisis within the Holy Roman Empire. That crisis was exacerbated by Europe’s inability to mount a united effort to prevent the Ottomans from seizing the Kingdom of Hungary – the most important of the Christian buffer states known as the Antemurales Christianitates. Ottoman successes were thus proof to a growing number of dissenters, notably the German monk and theologian Martin Luther, of the corruption plaguing Rome.

Thus, it is no coincidence that the Protestant Reformation began during the same period of Ottoman expansion into Europe, as more Diets were organized in a futile effort to seek aid to prevent a catastrophe from occurring. In 1521, four years after Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses in Nuremburg, the Diet of Worms was called, and Hungarian emissaries were sent to make appeals to the princes and representatives of the free cities of Germany to assist in that effort. In his seminal 1959 work, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 1521-1555, historian Stephen A. Fischer-Galati, wrote that “Louis’ envoys asked for preventative aid in the event of a Turkish attack, stressing the importance of Hungary as a buffer state between Germany and the Ottoman Empire.” However, that attempt was unsuccessful, as Germans dismissed the pleas of Hungarians, partly out of suspicion of Habsburg aspirations.[2]

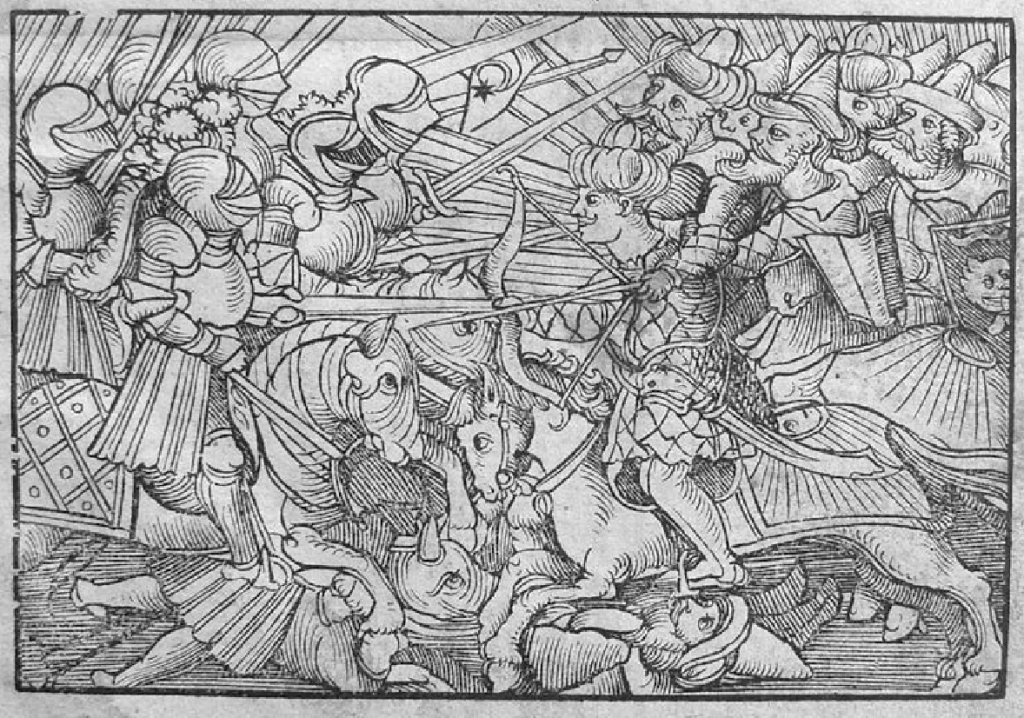

Battle of Mohacs, 1526

In 1522 Belgrade, the bulwark to Ottoman encroachment on the Danube, was captured by Suleiman’s forces. This prompted attempts to garner German support in the spring by delegates from Austria and Croatia, who represented the Hungarian plight. The result of that Diet was an agreement by the Reichstag to send 3,000 soldiers, the formation of a commission to meet in Vienna to address the situation, and a request to Emperor Charles V to make a truce with France. Nevertheless, despite the results, “the estates made an ineffective attempt to link the Hungarian crisis to the German.” In the fall of 1522, the second Diet of Nuremberg was held with little or no change in the position of the Reichstag regarding Hungary. The princes and representatives of the free cities made a renewed request to Charles to make peace in the West, and they contributed a scant 4,000 soldiers to Hungary’s defense – despite a request for 24,000 men.[3]

During this period the relationship between Charles and the Reichstag worsened. Incapable of listening to his brother Ferdinand’s demands for assistance, Charles rejected a request made by the Diet to hold a general council when a delegation was sent to him following renewed discussions in Nuremberg in 1524. It was at this Diet that the estates agreed to the formation of an army of 16,000 soldiers in the event that Germany was threatened by the Ottomans. However, no decisive commitment was made by Charles concerning Hungary, and this made the Germans reluctant to support the cause, which developed into a religious issue:

By the summer of 1526 when a new Diet met in Speyer the Hungarian situation became critical. The Turks were about to launch a decisive campaign against Louis’ [Hungarian] kingdom, and Ferdinand was gravely concerned… Angered by Charles’ refusal to call a council, the estates declined to consider the question of assistance to Hungary before solving the religious issues itself, subject to the ultimate ratification by a general Christian council to be summoned by the Holy Roman Emperor. [4]

Inaction put Ferdinand – a rather inexperienced intermediary between Charles and the Reichstag – in a difficult position. Faced with the possibility of a Hungarian collapse, Ferdinand made a deal with the Reichstag by agreeing to convene a council in eighteen months devoted to the protesters’ religious questions in exchange for immediate assistance to Hungary. “On July 27, 1526 the Emperor authorized Ferdinand to advise the Diet of his decision to negotiate with Pope Clement VII with a view of Summoning a council.” After this key concession was made “the estates agreed to send 24,000 men at once to help the Hungarians.“ The gesture was of little avail; the Diet adjourned on August 27 and four days later, the Ottomans defeated the Christians at the Battle of Mohacs.[5]

John Zapolya and the Buffer State

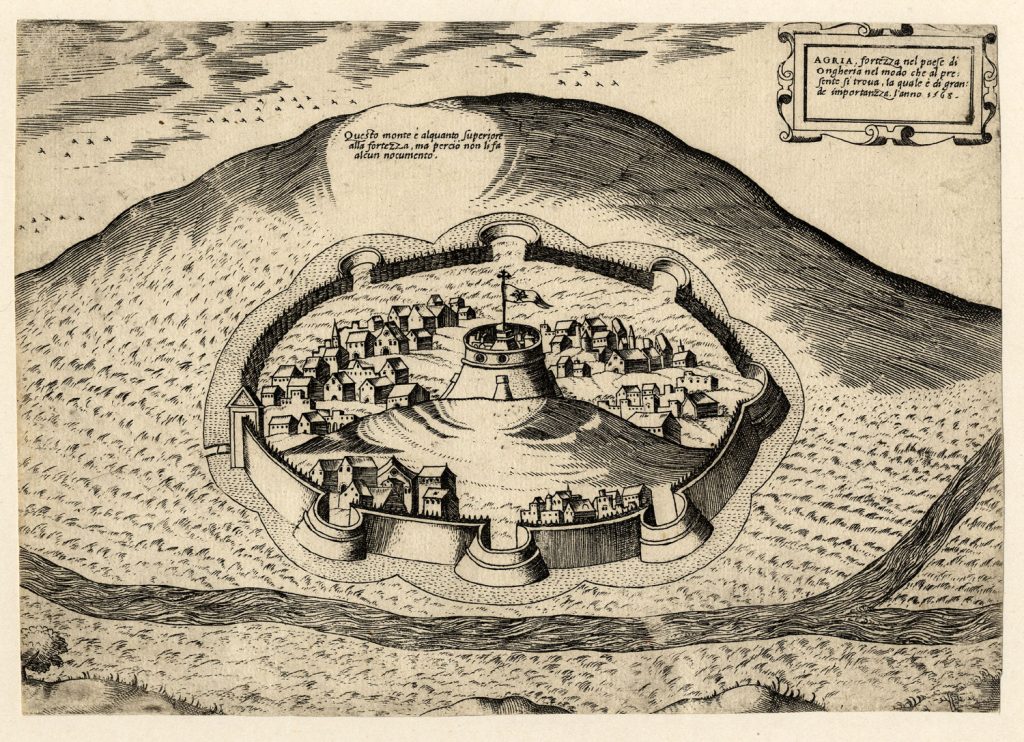

Nowhere was the Ottoman influence on the Reformation more relevant than in Hungary. The vassal state on the farthest western reaches of their empire and gateway into the Upper Palatinate, Hungarian lands became the border between the two empires, and seeing that the Reformers were opposed to Roman and Habsburg domination of the Holy Roman Empire, Protestantism found fertile soil in territories controlled and administrated by the Ottomans. In his 1973 work, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1600, Halil Inalcik writes, “The Turks were not interested in one or the other religion. Their aim was economic exploitation and the protection of their country on foreign soil.” In essence, unlike Muslim enclaves closer to their capital, there was very little effort by the Ottomans to force Hungarians into the Muslim faith because it served their strategic purposes to have a dissenting sect from the Roman Catholic Church within their borders. “Support and protection of the Lutherans and Calvinists against Catholicism would be the keystone of Ottoman policy in Europe. Ottoman policy was thus intended to maintain the political disunity in Europe, weaken the Habsburgs and prevent a united crusade.”[6]

Opposed by Ferdinand, Hungarian king John Zapolya and the magnates supporting a more politically independent Hungary viewed the Treaty of Pressburg in 1491 between Frederick III of Habsburg and Ladislas of Bohemia as a violation and usurpation of their sovereignty. The idea of Hungarian independence originated in the days of the Golden Bull (1222), a time when the Byzantines controlled the Balkans and parts of Hungary. For Hungarian (Magyar) nationalists disgusted with the Church and Holy Roman Empire, the Ottoman invasion– particularly in the wake of Mohacs – was seen as a means to achieve autonomy from the Habsburgs and in many respects the influential German-speaking communities within the realm.

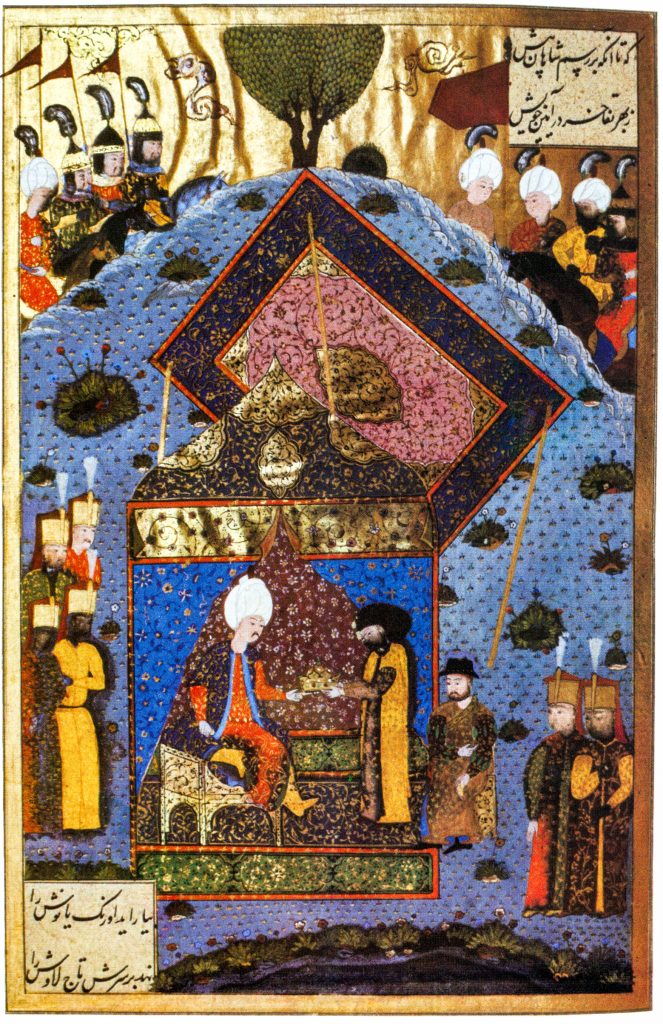

Thus, Suleiman supported Zapolya because the relationship offered the Ottomans a buffer state between Habsburg control while at the same time allowing Hungarian reformers (and German holdouts in Transylvania) to begin the process of the Reformation. For that reason, Suleiman saw no need to appoint an Ottoman overlord to oversee the kingdom because his former enemy (Zapolya) was eager to resist the Habsburgs. To counter this development, in 1527 Ferdinand sent German mercenaries to depose Zapolya:

The Ottomans withdrew from Hungary, occupying only Srem, and the Hungarian Diet elected John Zapolya [governor of Transylvania since 1510] as King. At first the Ottomans wished to make Hungary a vassal state, like Moldavia, since it was considered too difficult and too expensive to establish direct Ottoman rule in a completely foreign country on the far side of the Danube. But the Hungarian partisans of the Habsburgs elected Charles V’s brother, Archduke Ferdinand, King of Hungary, and in the following year he occupied Buda and expelled Zapolya.[7]

As a result, Suleiman invaded Hungary again in 1529 and “enthroned Zapolya in Buda as an Ottoman vassal. Zapolya agreed to pay an annual tribute and accepted a Janissary garrison in the citadel.” Moreover, according to Fischer-Galati, the Ottomans laid siege to Vienna later that year not to conquer Germany, but to “to warn the Hapsburgs that interference in Hungary, the western bastion of the Ottoman Empire, would not pass unchallenged.”[8]

Fostering the Hungarian Reformation

Until the end of the seventeenth century Hungary remained under Ottoman rule. Under occupation Protestantism found fertile soil in Hungary. Christian historian William Toth wrote in 1940 that “Following the defeat of Mohacs in 1526, both the preachers and the adherents of the new movement increased, as it were, by leaps and bounds.”[9]

Protected by the recent conquerors, the reformation of the Christian churches in Hungary found minimal interference from papal initiatives. In addition, the inability to come to the aid of a Christian state in dire need leading up to Mohacs would not be forgotten among reform-minded clergy following the change of imperial masters. “The Turks even went so far as to protect the adherents of the new faith,” Toth wrote, “if need arose, by military force.” Even though “Hungarian Protestants considered the Turks, as a rule, the scourge of God,” they were more or less free to conduct ecclesiastic affairs and reforms without manipulation from Rome.[10] The result of that relative freedom was the spread Lutheranism, and then Calvinism from the alpine regions of Switzerland into Hungary and other corners of Europe, such as Scotland – a movement one historian has labeled the “second wind of Protestant religious reform…” Although appealing at first, Lutheranism had been associated in Hungary as a sect distinct to ethnic Germans, and thus Calvinism, in its international form, appealed to non-German Hungarians. Various religious leaders emerged in Hungary and Transylvania during the Reformation. Among them, John Sylvester, Matthias Biro of Deva, Stephen Kis of Szeged, Matthew Skaricza, Peter Melius, Michael Sztarai, Francis David of the Unitarian Church in Transylvania, and John Honterus of the German Lutheran Church of Transylvania. In Hungary-proper Calvinism took hold while in Transylvania the Saxons maintained their allegiance to Lutheranism, splitting eventually with Calvinism on the sacraments. This is the legacy of the Ottoman influence on the Reformation.[11]

[1] John Dillenberger, ed., Martin Luther: Selections of His Writings (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1961), 431. See: John W. Bohnstedt, “The Infidel Scourge of God: The Turkish Menace as Seen by German Pamphleteers of the Reformation Era,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 58, no. 9 (1968): 1–58.

[2] Stephen A. Fischer-Galati, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 1521-1555 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959), 18-19. On the Diets, Fischer-Galati cites: A Kluckhohn et al., ed., Deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V, [I 521-1526. 1-IV]. (Gotha, 1893), II, 167 ff.

[3] Ibid, 20. Deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V, III, 218-219, 338 ff. The capture of Rhodes in 1522, an island used by the Knights of St. John as a base of operations since the Crusades, marked the end an era of Christian dominance in the region.

[4] Ibid. 21-25. “W. Friedensburg, Der Reichstag zu Speier 1526 (Berlin 1887) is still the only comprehensive treatment of the subject.”

[5] Ibid. 25-27. Charles to Ferdinand, July 27, 1526. “On Charles’ aims and foreign policy consult his correspondence with Ferdinand in W. Bauer and R. Lacroix, eds., Die Korrespondenz Ferdinands I.” (Wien, 1912), I, 408 ff.

[6] Halil Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1600 (London: Phoenix Press, 1973), 37.

[7] Ibid. 35

[8] Halil Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire, 36; Fischer-Galati, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 36-38.

[9] William Toth, “Highlights of the Hungarian Reformation,” Church History 9, no. 2 (June 1940), 152.

[10] William Toth, “Highlights of the Hungarian Reformation,” 149.

[11] Graeme Murdock, Calvinism on the Frontier 1600-1660 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, 2000), 1-9.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.