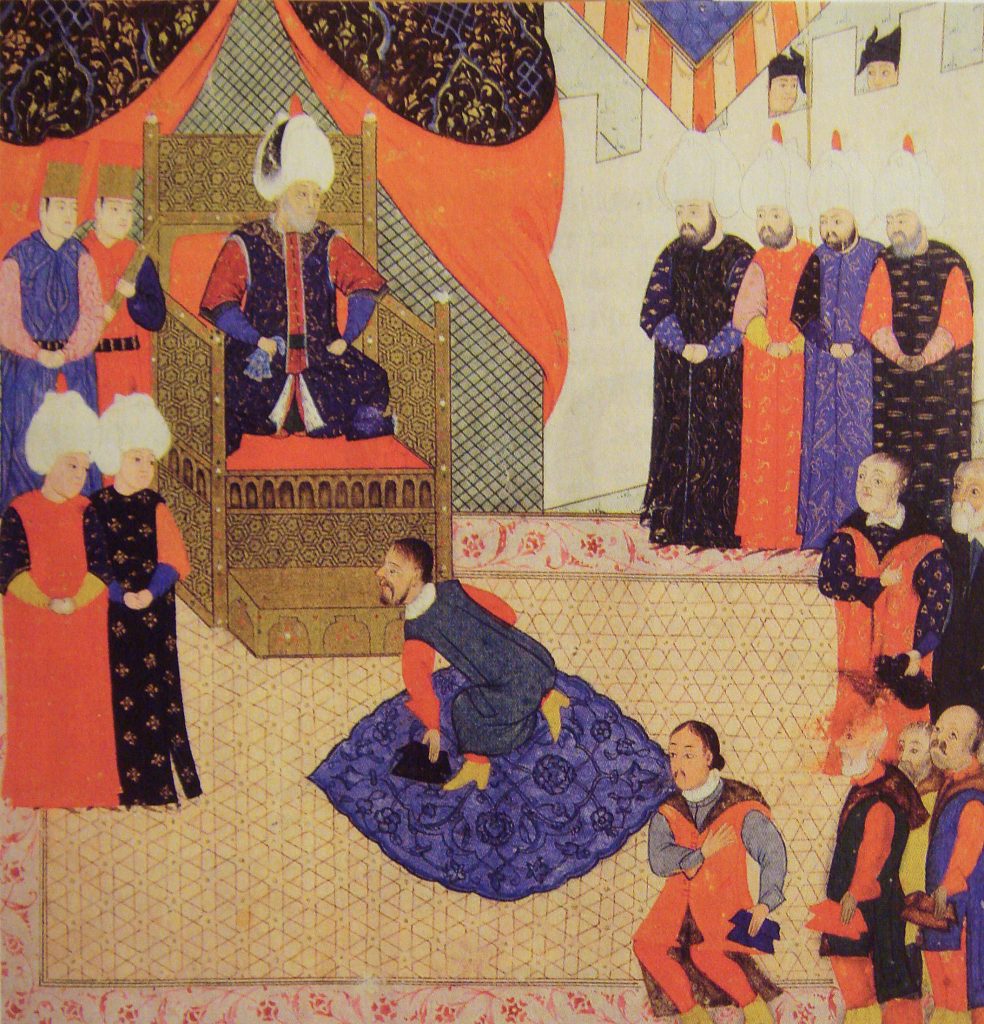

The Battle of Mohács 1526 by Bertalan Székely (1835–1910)

It is unquestionable that the real Roman empire perished and ended long ago. This empire and its destruction …took place at the hands of the Goths, but was confirmed when the Turkish empire arose a thousand years ago. In the course of time, Asia and Africa, and afterwards France and Spain, and finally Venice, fell away, and nothing remained to Rome of its former power.[1]

Martin Luther, 1520

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 thrust the Ottoman Empire to the center of European affairs. News of the final collapse of the old (Eastern) Roman Empire spread rapidly throughout the continent and calls to fight the infidels were made by kings, nobles, and clergy alike. The Ottomans conquered the remnants of a once vast empire that lasted until the end of the First World War, and impacted the course of Western history by influencing the religious Reformation of the early sixteenth century.

During this political and religious crisis, southeastern Europe ultimately fell and with it the Kingdom of Hungary – the most important of the Christian buffer states (Antemurales Christianitates). The public acrimony disseminated during those years, most notably by the Thuringian priest and theologian Martin Luther, reflected a growing displeasure with Rome amongst the Germans – contrasting secular Ottoman efficiency and their employment of Christian soldiers. To men like Martin Luther, Ottoman successes were proof of the Holy Roman Empire’s corruption and need for reform:

Since, therefore by the providence of God and the efforts of evil men, the empire has been given us through no fault of ours, I do not believe we ought to abandon it; but, rather, to administer it properly in the fear of God, as long as it may please Him. For, as I have said, He does not look to see whence an empire arose; His will is that it should be rightly administered. Though the popes took it improperly from others, we did not receive it improperly. It has been given to us by God’s will through the hands of wicked men. We rely on Him more than on the false intentions which the popes had at the time when their object was to become emperors, and more than emperors themselves, while merely tricking us with the name, and scorning us.[2]

Dissenters within the Holy Roman Empire advocated reforming church doctrine, particularly the selling of indulgences to finance papal projects and provide security against the common threat. However, leadership was unprepared to deal with Ottoman advancement, and the need to mount campaigns against the enemy exposed the weakness of a system managed under an antiquated bureaucracy and inflexible hierarchy.

Moreover, there was no standing army in Europe at the time, and defense was discussed collectively. Reformers warned of a pending Ottoman advance, but little was done to stop the highly efficient Ottoman war machine from spreading further into Europe.[3]

The Ottoman Army

The boundary between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire reached its furthest extent following Suleiman the Magnificent’s victory at Mohacs in 1526 and subsequent occupation of Buda. The borders of the growing empire stretched from the shores of the Black Sea, through the Carpathian Mountains, across the Danube River and the plains of Hungary, and south between Bosnia and Croatia to the Adriatic Sea.

The territories of the Balkans – formerly Byzantine possessions in the Middle Ages, were conquered swiftly by the Ottomans – who had since the late thirteenth century developed a highly effective military-land-tax system that incorporated Christian fighters into an army managed by Muslim commanders. Serbia was overrun as early as 1389 (although not absorbed) and Wallachia in Romania had been a tributary as early as 1417.

Prior to the conquest of Constantinople, the Ottomans began placating Orthodox Christians by marrying into Byzantine and Balkan dynastic families, as well as tolerating existing Christian practices. In addition, the Ottomans employed a draft system (devshirme) conscribing children of Christian and Jewish parents into the military. This practice began in the middle fourteenth century. These Janissaries, as they were known, ascended in rank and social status during the early period of Ottoman history, and had a profound impact on the empire.

Kingdom of Hungary, Rise of the Habsburgs, and Political Crisis

While Constantinople still stood as the eastern bulwark to Turkish domination, many Europeans considered Ottoman advances as raids – as opposed to the expansion of the borders of a menacing state. That changed after 1453 and the lead-up to the takeover of Hungary – itself once a powerful kingdom in Central Europe. In the fourteenth century, Louis the Great (1342-1382) began building the foundations of a strong, independent state in that region, and was followed by King Sigismund (1387-1437), who unsuccessfully “tried to rally Western Christendom against the ‘enemy of the faith.’”[4] The era marked the beginning of interaction between Ottomans and Hungarians, who were using the states of Wallachia, Serbia, and Bosnia, as proxies in their campaigns for regional dominance. “Caught between the rival claims of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, these buffer states struggled for their very existence.” It was during this period that the future figure of Hungarian nationalism, John Hunyadi, waged war against the invaders.[5]

The accession of Matthias Corvinus in 1458 marked a change in orientation from east to west, and he moved to conquer most of Austria (including Vienna) in 1485. Corvinus’s death in 1490 led to the collapse of a strong independent Hungarian state in Central Europe, and ushered in the rise of the powerful Habsburg dynasty, headed by Emperor Maximilian I, whose ambitious agenda included the capture of Venice and the Bohemian crown, and arrest of the Ottomans. In his 1959 work, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 1521-1555, the historian Stephen A. Fischer-Galati, wrote that “Maximilian had been the virtual head of the House of Hapsburg and the Holy Roman Empire since his election as King of the Romans in 1486. A dedicated exponent of the device, Austriae est imperare omni universo, he explored every opportunity to enhance the position of his family.”

Following Corvinus’s death, Hungarian magnates chose the weak Ladislas of Bohemia as their king so as to maintain their local control over Hungary. This upset Maximilian, whose father Frederick III had arranged his accession with Corvinus. Ultimately, Maximilian was forced – partly due to difficulties caused by the financially-draining Italian campaigns – to accept Ladislas’s rule. He was, however, able to arrange two important dynastic marriages in the 1491 Treaty of Pressburg:

In 1506, despite the opposition of the Hungarian magnates who expected their leader, John Zapolya, to succeed Ladislas, Maximilian was able to bring about the double betrothal between his granddaughter Mary and Ladislas’ infant son Louis, and one of his grandsons, Charles or Ferdinand [it would later be Ferdinand], to Louis’ sister Anna. It took Maximilian ten years to subdue the opposition of Zapolya and his party, but in 1515, by the Treaty of Vienna, be gained ratification of the arrangements of 1506.[6]

Maximilian’s death in 1519 marked the ascension of Charles V to the throne as Holy Roman emperor. Charles inherited an empire during a period of perpetual political chaos and war – as the Ottomans under the new leadership of Suleiman I were making inroads into the Balkans, as well as consolidating their control over formerly Byzantine territory stretching to the Red Sea. It was during these years that Charles’s brother Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria and the future inheritor of the Hungarian and Bohemian thrones, was put in charge of defending the Antemurales Christianitates, while Charles became preoccupied with his campaigns in France and elsewhere in the Mediterranean – a preoccupation that ultimately led to the abandonment of Hungary and political schism within the ‘universal’ church. In the end, the Ottomans encouraged that dissent, and the Hungarians no longer had anything to lose by leaving the orbit of Rome.

[1] John Dillenberger, ed., Martin Luther: Selections of His Writings (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1961), 476-77. An Appeal to the Ruling Class of German Nationality as the Amelioration of the State of Christendom. Chap. III, Twenty-Seven Proposals for Improving the State of Christendom. 1520.

[2] Ibid. 478-9.

[3] See: Stephen A. Fischer-Galati, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 1521-1555 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959); De Lamar Jensen. “The Ottoman Turks In Sixteenth Century French Diplomacy,” Sixteenth Century Journal 16, no. 4 (Winter 1985:): 451-470. Jensen’s research demonstrates the pragmatism of both Christian and Muslim powers. The French King Francis I believed the Ottomans were “the only power he considered to be capable of preventing the Habsburgs from dominating Europe.” (p. 452) Francis helped create a policy designed to put pressure on the Habsburgs. “Interpolating from the activities of Antonio Rincon, the French agent in Poland, and from the letters exchanged by Francis I with Sigismund of Poland and John Zapolya of Transylvania that culminated in the Franco-Hungarian alliance of 1528, it appears that Francis hoped to build up a broadly based anti-Habsburg eastern front, the southeastern sector of which would be secured by the Ottoman Turks.” (p. 452-3) Jensen cites: V. L. Bourrilly, “Antonio Rincon et la politique orientale de Francois fer, 1522-1541,” Revue historique 113 (1913): 64-83, 268-308. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, Collection Dupuy, 468, fol. 191. Charriere, Negociations/Levant, I:149-69. Ursu, La politique orientale, 40-50; also: Dorothy Vaughn, Europe and the Turk: A Pattern of Alliances, 1350-1700 (Liverpool University Press, 1954), 111-12. The Ottoman legacy of religious tolerance comes partly from their incorporation of Jews into Palestine and Istanbul when they fled Spain during the Inquisition.

[4] Fischer-Galati, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 2.

[5] Halil Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1600 (London: Phoenix Press, 1973), 20.

[6] Fischer-Galati, Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism, 2-8. See: Paula Sutter Fichtner, “Dynastic Marriage in Sixteenth-Century Habsburg Diplomacy and Statecraft: An Interdisciplinary Approach,” The American Historical Review 81, no. 2 (Apr. 1976): 243-265.

About the author

Benjamin J. Swenson is an assistant professor at Hoseo University in Asan, South Korea. He holds a PhD from Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, where his dissertation addressed Euro-American military history and the advent of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in the nineteenth century. His work has recently appeared in the Journal of Military History, and his latest, The Dawn of Guerrilla Warfare, will be published by UK’s Pen & Sword in 2023. His hobbies include Viking sagas and chess.

One thought on “The Ottoman Empire, Hungary, and the Protestant Reformation (I)”